Part 2 - Data Representation

Data: characters and integers. The binary addition algorithm.

Characters

Patterns of bits represent many types of things. This chapter shows how bit patterns are used to represent characters.

Chapter Topics:

- ASCII

- Control characters

- Teletype Machines

.asciizand null terminated strings- Disk files

- Text files

- Binary files

- Executable files

Question 1

What else (besides characters and integers) can be represented with bit patterns?

Answer

Machine instructions. (Many answers are correct; anything symbolic can be represented with bit patterns: graphics, music, floating point numbers, internet locations, video, ...)

Representing characters

A group of 8 bits is a byte. Typically one character is represented with one byte. The agreement by the American Standards Committee on what pattern represents what character is called ASCII. (There are several ways to pronounce "ASCII". Frequently it is pronounced "ásk-ee"). Most microcomputers and many mainframes follow this standard.

When a printer built to print ASCII receives the ASCII pattern for "A" (along with some control signals), it prints an "A". Printers built to other specifications (typically for mainframe computers) might print some completely different character if sent the same pattern.

Most modern printers are much more complicated than the one illustrated on the right. Typically, a modern printer is sent an entire file of information at once. The file describes the layout and contents of an entire page. ASCII characters are just some of the information in the file.

Question 2

(Thought Question: ) Does the DOS command TYPE expect a file containing ASCII characters?

Answer

Yes.

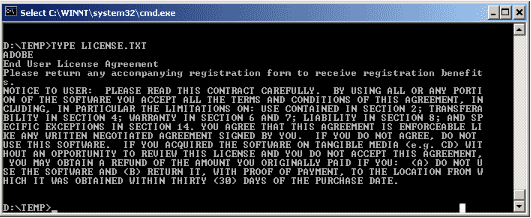

TYPE

The DOS command TYPE acts like an old-time printer. It interprets the bytes it is sent one-by-one, printing the corresponding character on the screen. Here is an example using a text (.txt) file:

Question 3

Do some files contain bit patterns that represent things other than characters?

Answer

Of course. Pure ASCII files are rare, these days.

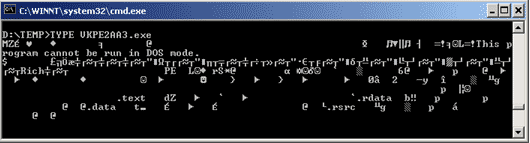

Wrong type of data

Most files contain information encoded by schemes other than ASCII. Executable files (.exe) mostly contain machine instructions. The TYPE command will not be successful in interpreting this information as character data. Here is what happens when TYPE is sent an executable file:

Only a limited range of byte patterns correspond to characters. The remaining patterns are sometimes called unprintable characters. Sometimes, depending on the application, the unprintable patterns correspond to special purpose characters or geometric shapes.

Most positions in the above picture are blank because TYPE could not interpret the corresponding byte as a character. Some positions are filled with special-purpose characters when a byte accidentally corresponded to a special purpose character. But some positions look like they correspond to legal ASCII.

Question 4

Is some of the information in the executable file encoded as ASCII?

Answer

Yes. It is common for files to use different schemes for different types of data.

Control characters

Some ASCII patterns do not correspond to a printable character. For example, the pattern 0x00 (i.e., 0000 0000) is the NUL character. NUL is often used as a marker in collections of data. The pattern 0x0A is the linefeed character (LF), sent to a printer to indicate that it should advance one line. The patterns 0x00 through 0x1F are called control characters and are used to control input and output devices. The exact use of a control character depends on the particular output device. Many control characters were originally used to control the mechanical functions of a Teletype machine.

Question 5

Could a computer terminal be a mechanical device???

Answer

tbdAnswer

Teletype machines

Teletype machines were used from 1910 until about 1980 to send and receive characters over telegraph lines. They were made of electrical and mechanical parts. They printed characters on a roll of paper. Various mechanical actions of the machine were requested from a distance by sending control characters over the line. A common control sequence was "carriage return" followed by "linefeed".

In the early days of small computers (1972-1982) Teletypes were often the sole means of input and output to the computer. These Teletype machines printed with fixed-size characters (like their electric typewriter cousins). The tag used in HTML for fixed-size (non-proportional) font is <tt> -- which stands for "TeleType". This paragraph is set inside <tt> ... </tt> tags.

(Sadly, the <tt> tag has been deprecated and is no longer used.)

Some models of Teletypes could be used off-line (not connected to anything). The user could slowly and carefully type a message (or program) and have it recorded as holes punched on a paper tape. The device on the left of the machine in the photo is the paper tape reader/puncher. Once the paper tape was correct, the Teletype was put on-line and the paper tape was quickly read in. In those days, paper tape was mass storage.

The Web pages of the North American Communications Museum Off-site link have more information on Teletypes.

Question 6

Can the bit patterns that are used to represent characters represent other things in other contexts?

Answer

Yes.

ASCII chart

| Hex Char | Hex Char | Hex Char | Hex Char |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00 nul | 20 sp | 40 @ | 60 ` |

| 01 suh | 21 ! | 41 A | 61 a |

| 02 stx | 22 " | 42 B | 62 a |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 0A if | 2A * | 4A J | 6A j |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1E rs | 3E > | 5E ^ | 7E ~ |

| 1F us | 3F ? | 5E _ | 7F del |

The chart shows some patterns used in ASCII to represent characters. (See the appendix for a complete chart.) The first printable character is SP (space) and corresponds to the bit pattern 0010 0000.

Space is a character, just like any other. Although not visible in the shortened chart, the upper case alphabetical characters appear in order A,B,C, ..., X, Y, Z with no gaps. There is a gap between upper case and lower case letters. The lower-case characters also appear in order a,b,c,...x, y, z.

The last pattern is 0x7F which is 0111 1111. This is the DEL (delete) character. For a complete list of ASCII representations, see the appendix.

Question 7

How many of the total number of 8-bit patterns correspond to a character, (including control characters)? (Hint: look at the pattern for DEL).

Answer

50 Percent, 128 out of 256

ASCII sequences

The chart for ASCII shows all possible 7-bit patterns. There are twice as many 8-bit patterns. Some computer makers use the additional patterns to represent various things. Old MS Windows PCs, for example, used these extra patterns to represent symbols and graphics characters. Some printers will not work with these additional patterns.

Part of what an assembler does is to assemble the ASCII bit patterns that you have asked to be placed in memory. Here is a section of an assembly language program:

.asciiz "ABC abc"

Here are the bit patterns that the assembler will produce in the object module:

41 42 43 20 61 62 63 00

The .asciiz part of the source code asked the assembler to assemble the characters between the quote marks into ASCII bit patterns. The first character, "A", corresponds to the bit pattern 0x41. The second character, "B", corresponds to the bit pattern 0x42. The fourth character, " " (space), corresponds to the bit pattern 0x20. The final bit pattern 0x00 (NUL) is used by the assembler to show the end of the string of characters.

Question 8

What will be the assembled patterns for this assembly code:

.asciiz "A B"

Answer

41 20 42 00

Files

Files consist of blocks of bytes holding bit patterns. Usually the patterns are recorded on magnetic media such as hard disks or tape. Although the actual physical arrangement varies, you can think of a file as a contiguous block of bytes. The "DIR" command of DOS lists the number of bytes in each file (along with other information).

Ignoring implementation details (which vary from one operating system to the next), a file is a sequence of bytes on magnetic media. What can each byte contain? A byte on a magnetic disk can hold one of (256) possible patterns, the same as a byte in main storage. Reading a byte from disk into a byte of main storage copies the pattern from one byte to another.

(Actually, for efficiency, disk reads and writes are always done in blocks of 128 bytes or more at a time).

So a file contains only bit patterns, as does main memory. What is represented by the bit patterns of a file depends on how they are used. For example, often a file contains bytes that represent characters according to the ASCII convention. Such a file is called a text file, or sometimes an ASCII file. What makes the file a text file is the knowledge about how the file was created and how it is to be used.

Question 9

You (acting as an "English Language Application") find a battered old book in a stall outside a bookshop. You open the book to a random page and see:

Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae.

Is this book suitable for you (in your role as an English application)?

Answer

No. The individual letters are the same as used in your expected context (English) but in the book their context is different.

Text files

A computer application (a program) provides the context for the bit patterns of the input and output files it uses. Although there are some standard contexts (such as for text files), many applications use a context that is their own. If you could somehow inspect the surface of a disk and see the bit patterns stored in a particular file, you would not know what they represented without additional knowledge.

Often people talk of "text files" and "MS Word files" and "executable files" as if these were completely different things. But these are just sloppy, shorthand phrases. For example, when someone says "text file" they really mean:

Text File: A file containing a sequence of bytes. Each byte holds a bit pattern which represents a printable character or one of several control characters (using the ASCII encoding scheme). Not all control characters are allowed. The file can be used with a text editor and can be sent to a hardware device that expects ASCII character codes.

Files containing bytes that encode printable characters according to the ASCII convention have about half of the possible patterns. Software that expects text files can work with the ASCII patterns, but often can't deal with the other patterns.

Question 10

A file compressor is a program that inputs a file and outputs a smaller file that uses bit patterns more efficiently that in the original file. A decompressor restores the compressed file to the original version.

(Thought Question: ) When an ASCII file is compressed, does the resulting file contain ASCII characters?

Answer

No. ASCII characters are wasteful of bits, since only seven of the eight bits are used. A compressed file makes better use of bit patterns. The bytes in the compressed file do not correspond directly to ASCII.

Executable files

When one says "executable file" one really means:

Executable File: A file containing a sequence of bytes. Each byte holds a bit pattern that represents part of a machine instruction for a particular processor. The operating system can load (copy) an executable file into main storage and can then execute the program.

A byte in an executable file can contain any possible 8-bit pattern. A file like this often is called a Binary File. This is misleading vocabulary. All files represent their information as binary patterns. When one says "MS Word file" one really means:

Word File: A file containing a sequence of bytes holding bit patterns created by the MS Word program, which are understood only by that program (and a few others).

There is nothing special about the various "types" of files. Each is a sequence of bytes. Each byte holds a bit pattern. A byte can hold one of 256 possible patterns (although some file types allow only 128 or fewer of these patterns). When longer bit patterns are needed they are held in several contiguous bytes.

Question 11

Say that you compress a text file with a file compression utility. What is the minimum compression can you expect?

Answer

By using all the bits of a byte, a text file, at the minimum, could be compressed to 7/8 of its original size. In fact, compression utilities can do much better than this and typically compress a text file to 50% or less of its original size.

Binary file

All files are sequences of bytes containing binary patterns (bit patterns). But people often say binary file when they mean:

Binary File (colloquial): a file in which a byte might contain any of the possible 256 patterns (in contrast to a text file in which a byte may only contain one of the 128 ASCII patterns, or fewer).

An EXE file is a binary file, as is a Word file, as is an Excel file, as are all files except text files. People are often not careful, and sometimes say "binary file" when they really mean "executable file". The phrase "binary file" became common among MS/DOS users because DOS file utilities made a distinction between text files and all others.

Using the wrong type of file with an application can cause chaos. Don't send an executable file to a printer, or open an MS Word file with a text editor. Some applications are written to deal with several types of files. MS Word can recognize text files and files from other word processors.

Question 12

Why are word processor files not text files?

Answer

Many types of data are represented in a word processor file, not just the characters of ASCII. A word processor file must also represent fonts, character sizes, formats, colors, graphics, etc. All these things are represented with bit patterns. Different word processors use different bit patterns to indicate these things.

Chapter quiz

Question 1

How many bits are in a byte on most computers?

- (A) 2

- (B) 4

- (C) 6

- (D) 8

Answer

D

Question 2

About how much data does one byte correspond to?

- (A) One character.

- (B) One floating point number.

- (C) One machine instruction.

- (D) One signal.

Answer

A

Question 3

What is the NUL byte?

- (A) a byte that contains all zeros.

- (B) a byte that contains all ones.

- (C) a byte that contains no bits.

- (D) a byte that contains any illegal pattern.

Answer

A

Question 4

What is a control character?

- (A) A byte pattern that corresponds to any non-alphabetic and non-digit character.

- (B) The signal that shifts the carriage from lower case to upper case.

- (C) A byte pattern that originally was intended to ask for a mechanical action of an output device.

- (D) Any character that takes up more than one byte.

Answer

C

Question 5

What is a teletype machine?

- (A) An early model of personal computer.

- (B) An early type of printer that punched holes instead of using ink.

- (C) A mechanical device used to send and receive printed text across telegraph lines.

- (D) An early adding machine that used mechnical parts rather than electronics.

Answer

C

Question 6

What is the name of the convention that says how bit patterns are used to represent characters.?

- (A) DOS

- (B) ASCII

- (C) HTML

- (D) AIISC

Answer

B

Question 7

If characters are arranged in numeric order, what is the first printable character?

- (A) A

- (B) 0

- (C) @

- (D) space

Answer

D

Question 8

What type of file that contains only bytes that correspond to printable characters and a small number of control characters?

- (A) text file

- (B) type file

- (C) control file

- (D) word file

Answer

A

Question 9

What do people sometimes call a file that contains bytes that can potentially hold any bit pattern?

- (A) text file

- (B) data file

- (C) binary file

- (D) ASCII file

Answer

C

Question 10

How many patterns can be made out of eight bits?

- (A) 8

- (B) 128

- (C) 256

- (D) 1024

Answer

C

Number Representation

Patterns of bits can represent many different things. Anything that can be represented with symbols of any kind can be represented with bit patterns. This chapter shows how bit patterns are used to represent integers.

- Numbers and representations of numbers.

- Positional representation of integers.

- Decimal representation.

- Binary representation.

- Converting representations.

Question 1

What is your favorite number?

Answer

VII

What is a number

In ordinary English, the word "number" has two different meanings (at least). One meaning is the concept, the other meaning is how the concept is represented. For example, think about

"the number of eggs in an egg carton"

You know the number I mean. Now write it down on paper.

Question 2

How many eggs in a carton of eggs?

Answer

12

Representations

What you wrote is a representation of the number. Here is one representation:

XII

This may not be the representation you used for your number. Here is another representation for that same number:

///// ///// //

Perhaps you used this representation:

12

or this:

twelve

or this:

11002Question 3

Are XII, ///// ///// //, and 12 different numbers?

Answer

No, but the question is vague.

Representations

To be precise you would say that XII, ///// ///// //, and 12 are different ways to represent the same number.

There are many ways to represent that number. The number is always the same number. But a variety of ink marks (or pencil marks, or chalk smudges, or characters on a computer monitor) can represent it. In normal conversation and in writing "number" often means the representation of a number. For example, you might call

12

a "number". It would be tedious to call it "an instance of the representation of a particular number using Arabic digits with the decimal system." But that is what it is.

Computer Science is concerned with using patterns of bits to represent things. It is important to be clear about the difference between the thing, and a representation of the thing. For example, an integer may be represented using a bit pattern in computer memory. (There are many different ways to do this.) The integer is conceptual. The bit pattern is only a representation of the concept.

Question 4

Is XII even or odd?

Answer

Even. The representation does not change the properties the number (although it often makes it easier to determine those properties).

Positional notation

The decimal system is a positional notation for representing numbers. This means that the representation consists of a string of digits. The position of each digit in the string is significant. Think of each position as a numbered slot where a digit can go.

____4 ____3 ____2 ____1 ____0Positional notation has many advantages. It is compact: "78" is shorter than "LXXIIX". Computation is easy. LXXIIX times XLIIV is hard to do using the Roman system.

Question 5

Is XLMCIIV a legitimate Roman-system representation of an integer?

Answer

Yuck!

Decimal notation

The Roman numeral above is not a correct representation of an integer. But it takes some inspection to decide this. Decimal positional representation is clearly better.

You already know how decimal notation works (and probably would be happy to skip this topic).

324 means: 3 × 100 + 2 × 10 + 4 × 1

which is: 3 × 10^2 + 2 × 10^1 + 4 × 10^0

Remember that:

B^0 = 1, no matter what number B is.

Rules for Positional Notation.

- The base B is (usually) a positive integer.

- There are B "digits" representing zero up to (B minus one).

- Positions correspond to integer powers of B, starting with power zero, and increasing right to left.

- The digit placed at a position shows how many times that power of B is included in the number.

Question 6

Fill in the blanks with the appropriate power of 10:

7305 = 7 × 10^? + 3 × 10^? + 0 × 10^? + 5 × 10^?

Answer

7305 = 7 × 10^3 + 3 × 10^1 + 0 × 10^1 + 5 × 10^0

Decimal notation

For base 10 representation (often called decimal representation), the rules of positional notation are:

- The base is 10.

- There are 10 digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 .

- Positions correspond to integer powers of 10, starting with power 0 at the rightmost digit, and increasing right to left.

- The digit placed at a position shows how many times that power of 10 is included in the number.

A compact way of writing this is:

Any integer can serve as the base for a positional representation system. Five can serve as a base.

Question 7

Here are the rules for positional notation. Fill in the blanks to work with base five:

- The base is

___. - There are

___"digits":___,___,___,___,___. - Positions correspond to integer powers of

___, starting with power___at the rightmost digit, and increasing right to left. - The digit placed at a position shows how many times that power of

___included in the number.

Answer

- The base is

five. - There are

five"digits":0,1,2,3,4. - Positions correspond to integer powers of

five, starting with power0at the rightmost digit, and increasing right to left. - The digit placed at a position shows how many times that power of

fiveincluded in the number.

Base five notation

The number "five" in base five is represented by "10" That is:

1 × (five)^1 + 0 × (five)^0

The base in any positional representation is written as "10" (assuming that the usual symbols 0, 1, ... are used). Here is a number represented in base five: 421. It means:

421 = 4 × five^2 + 2 × five^1 + 1 × five^0

Remember, the symbol "5" can not be used in the base five system. Actually, the above sum should be written as follows. (This looks just like base ten, but remember, here "10" is "five".)

421 = 4 × 10^2 + 2 × 10^1 + 1 × 10^0

To avoid confusion, sometimes the base being used is placed as a subscript: means that base 5 is being used. It is conventional to show the subscript in base 10.

Question 8

Fill in the table. Each row shows two representations of the same integer. The column on the left represents it in base five, the column on the right represents it in base ten (except you have to fill in that column.)

| Base five representation | Base ten representation |

|---|---|

| 0 | ___ |

| 1 | ___ |

| 2 | ___ |

| 3 | ___ |

| 4 | ___ |

| 10 | ___ |

| 11 | ___ |

| 12 | ___ |

Answer

| Base five representation | Base ten representation |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 10 | 5 |

| 11 | 6 |

| 12 | 7 |

Changing representations

You may wish to change the representation of a number from base 5 notation into base 10 notation. Do this by symbol replacement. Change the base 5 symbols into the base 10 symbol equivalents. Then do the arithmetic in base 10.

The above process is often called "converting a number from base 5 to base 10". But in fact, the number is not being converted, its representation is being converted. The characters "421 (base five)" and "111 (base ten)" represent the same number.

Question 9

Change the representation of from base five to base ten.

Answer

Base seven

Here is another example: . This means:

3 × seven^2 + 2 × seven^1 + 6 × seven^0

To write the number in decimal, write the powers of seven in decimal and perform the arithmetic:

3 × 7^2 + 2 × 7^1 + 6 × 7^0 =

3 × 49 + 2 × 7 + 6 × 1 =

147 + 14 + 6 = 167

Question 10

Can be rewritten in base ten notation?

Answer

No. It is a meaningless representation because the digit 8 can not be used with base seven.

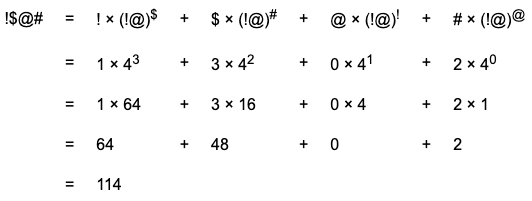

Secret numbers

The symbols chosen for digits need not be the usual symbols. Here is a system for base four:

zero == @ one == ! two == # three == $

Here is a number represented in that system: !$@#

Here is what that means in positional notation:

!$@# == !×(!@)$ + $×(!@)# + @×(!@)! + #×(!@)@

The base in this system is written !@ which uses the digits of the system to mean one times the first power of the base plus zero times the zeroth power of the base.

This example illustrates that positional notation can be used without the usual digits 0, 1, 2, ..., 9. If the base is B, then B digit-like symbols are needed.

Question 11

What is the base ten representation of !$@#?

Answer

Bit patterns

Bit patterns like 10110110110 are sloppily called "binary numbers" even when they represent other things (such as characters or machine instructions).

But, of course, bit patterns can be used to represent numbers. Base two positional notation is used for this.

Question 12

Fill in the blanks in the rules for base TWO positional notation:

- The base is

___. - There are

___"digits":___,___,___,___,___. - Positions correspond to integer powers of

___, starting with power___at the rightmost digit, and increasing right to left. - The digit placed at a position shows how many times that power of

___included in the number.

Answer

- The base is

2. - There are

2"digits":0,1. - Positions correspond to integer powers of

two, starting with power0at the rightmost digit, and increasing right to left. - The digit placed at a position shows how many times that power of

twoincluded in the number.

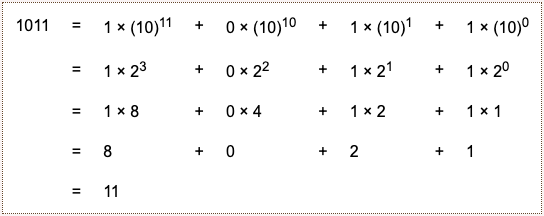

Representing numbers using base two

From the rules for positional notation there are two digits. Usually "0" and "1" are chosen, and usually the word bit is used. "Bit" is an abbreviation of "binary digit".

In this system the base, two, is written "10", the first power of two plus zero times the zeroth power of two. Each place in a representation stands for a power of two. Often this is called the binary system. Here is an example:

The first line above is written entirely in base two, and shows what the string "1011" means with positional notation. Both the base its powers are written in base two. The next line uses decimal notation for the base and its powers. The remaining lines use base ten arithmetic until finally the integer is expressed in base ten positional notation.

Question 13

What is 0110 (binary representation) in base ten?

Answer

0110 = 0 × 2^3 + 1 × 2^2 + 1 × 2^1 + 0 × 2^0

= 0 + 4 + 2 + 0

= 6

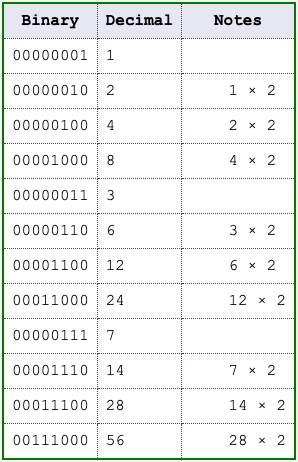

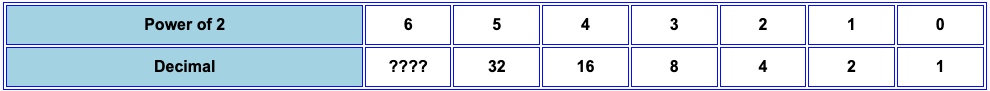

Powers of two

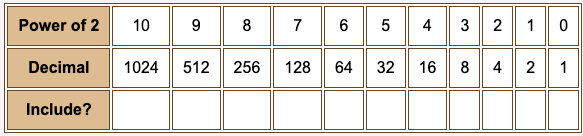

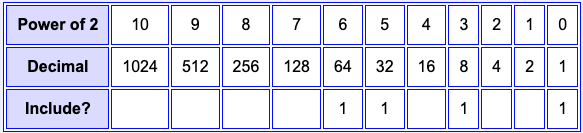

In a binary representation a particular power of two is either included in the sum or not, since the digits are either "1" or "0". In converting representations, it is convenient to have a table.

Here is an 8-bit pattern: 0110 1001. If it represents a number (using binary positional notation), convert the notation to decimal by including the powers of two matching a "1" bit.

Question 14

Copy 1s from the bit pattern to the last row of the table, starting at the right. Compute the sum of the corresponding decimal numbers.

Answer

Here is an 8-bit pattern: 0110 1001.

Sum = 64 + 32 + 8 + 1 = 105_10

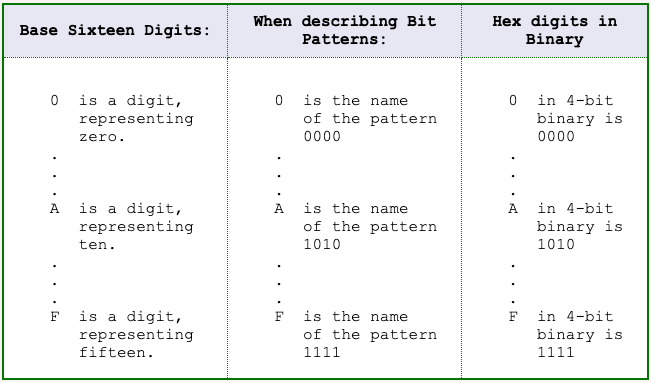

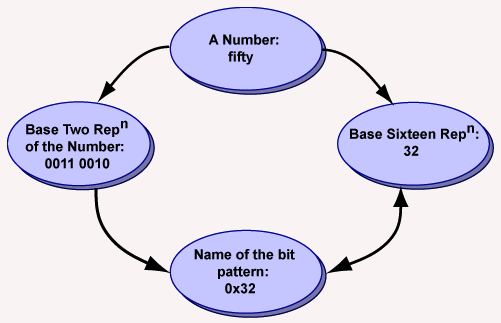

Binary and Hex Representation

Base 16 is often used to represent integers. Integers represented in base 16 are said to be represented with hexadecimal notation. The hexadecimal representation of an integer is equivalent to the pattern name of the bits in the binary representation of the integer.

It is easy to convert the representation of an integer between binary and hexadecimal. Converting representations between decimal and an arbitrary base is somewhat more difficult. The chapter presents some algorithms for doing this.

Chapter Topics:

- Left and right shifts

- Unsigned binary representation

- Familiar binary integers

- Hexadecimal representation

- Equivalence of hexadecimal representation and bit pattern names

- Converting representations from hexadecimal to binary

- Converting representations from decimal to any base

Question 1

A particular number is represented by 1010 (binary representation). What is the number represented in base ten?

Answer

1010 = 1 × 2^3 + 0 × 2^2 + 1 × 2^1 + 0 × 2^0

= 8 + 0 + 2 + 0

= 10

1010 = 10_10

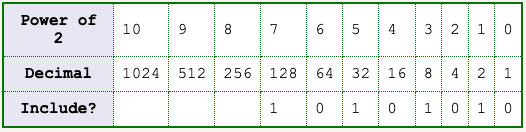

It is convenient to remember that . If you know it, then it takes just a moment to recognize

and other such computations. To convert larger binary representations to decimal representation, use a table. You can create this table from scratch by multiplying the decimal values by two starting on the right.

Think of the bits of the binary representation as turning on or off the numbers to include in the sum. For example, with 1010 1010 the various powers are turned on, as above.

Question 2

A particular number is represented by 1010 1010 (binary representation). What is the number represented in base ten?

Answer

Adding up the "turned on" powers of two gives:

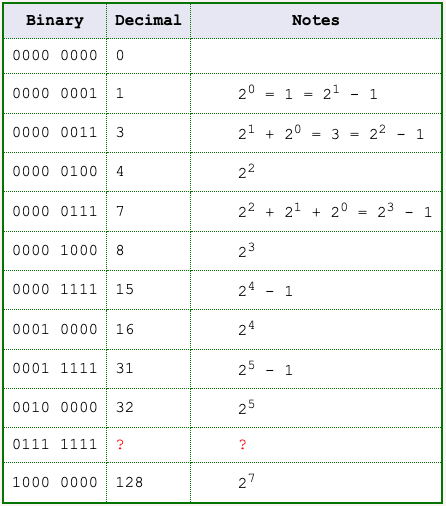

Favorite binary numbers

Here is a list of positive integers represented in both 8-bit binary and decimal. You will encounter these patterns frequently. For now, only positive integers are represented. Negative integers come later.

Look at the table and see if you can discover a useful pattern.

Question 3

An important number was left out of the table. What do you suppose is the decimal equivalent of 0111 1111?

Answer

You may have noticed that 0111 1111 is one less than 1000 0000, which is 128. So 0111 1111 represents of 127_10.

Further famous bit patterns

If a number is represented with all ones on the right and all zeros on the left, like this: 0011 1111. To find the decimal equivalent, turn on the bit to the left of the left-most one and then turn off all other bits. Compute the decimal equivalent of the resulting pattern and then subtract one.

For example, the equivalent of 0011 1111 is 0100 0000 - 1.

The decimal value corresponding to the single "on" bit is 64 and 64 - 1 = 63.

Here is another table of bit patterns (regarded as representing positive integers) and their decimal equivalent. See if you can notice something interesting.

Question 4

The bit pattern 0011 0010 represents . What bit pattern represents ?

Answer

0011 0010 = 5010; so 0110 0100 = 10010Left shift

Useful Fact: If the number N is represented by a bit pattern X, then X0 represents 2N.

If 00110010 represents 5010, then 001100100 represents 10010. Often you need the "shifted" pattern to have the same number of bits as the original pattern. Doing this with eight bits, 01100100 represents 10010.

This is called "shifting left" by one bit. It is often used in hardware to multiply by two. If you must keep the same number of bits (as is usually true for computer hardware) then make sure that no "1" bits are lost on the left.

Question 5

With 8 bits, there are patterns. What is the largest positive integer that can be represented in 8 bits using base two?

Answer

There are 256 patterns possible with 8 bits. But when these patterns represent integers, One of the patterns (0000 0000) is used for zero.

Unsigned binary

The representation scheme we are looking at is called unsigned binary because no negative numbers are represented. Often when people say "binary number" this is usually what they mean. Here are some of its characteristics:

- With

Nbits, the integers0,1,2,...,2N - 1can be represented.

- So, for instance, with 8 bits, the integers

0,1, ...,28 - 1can be represented. This is0 ... 255.

- With

Nbits, zero is represented by0....0....0(all0's). (2N - 1)is represented by1....1....1(all1's).

These facts are NOT always true for other representation schemes! Know what scheme is being used before you decide what a pattern represents.

Question 6

Without doing any calculation, which of the following is the decimal equivalent of 1111 1111 1111?

204840951638418432

Look at fact 3 in the list and think a bit.

Hint: Actually, you should think about a bit.

Answer

4095

Hopefully you did something clever: you realized that the represented number is 2^N - 1 which must be an odd number. (2^N means 2 × 2 × 2 ... × 2 it must be even. So 2^N - 1 must be odd.)

So you picked the only odd number in the list. Or else you ignored the question.

Base 16 representation

Recall the Rules for Positional Notation:

- The base B is (usually) a positive integer.

- There are B "digits" representing zero up to (B minus one).

- Positions correspond to integer powers of B, starting with power zero, and increasing right to left.

- The digit placed at a position shows how many times that power of B is included in the number.

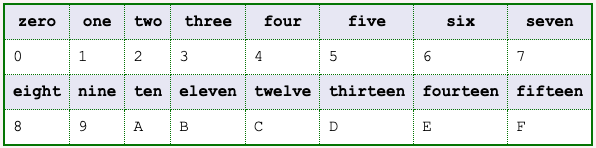

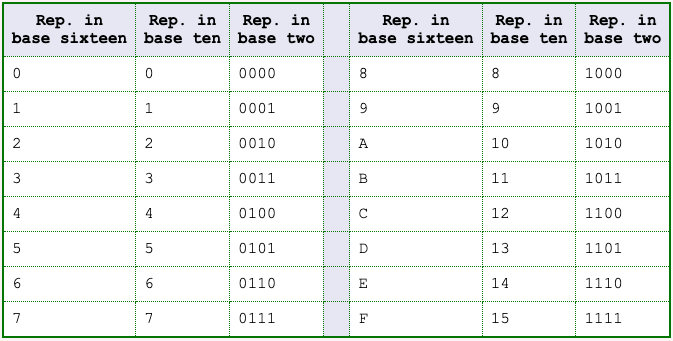

Rule 1 says any positive integer can be used as a base. Let's use sixteen as a base. Rule 2 says we need sixteen symbols to use as digits. Here is the usual choice:

Since there are only ten of the usual digits, letters are used for the remaining six hex "digits".

Base sixteen representation is called the Hexadecimal system, sometimes called Hex.

Question 7

Fill in the blanks with BASE SIXTEEN digits:

31A (base sixteen) = ___ x sixteen^2 + ___ x sixteen^1 + ___ x sixteen^0

Answer

31A (base sixteen) = 3 x sixteen^2 + 1 x sixteen^1 + A x sixteen^0

Converting a hex representation to decimal

To convert a hexadecimal representation of an integer to base 10, write the integer as a sum of hex digits times the corresponding power of 16 for each digit's position. Then, write the digits and the powers of 16 in base ten, and do the arithmetic.

You don't have to remember powers of 16 to do this conversion. All you need is powers of 2. For example,

Another example:

Question 8

More practice: What is the integer (represented in base 10) that is represented by 1B2 (base sixteen)?

Answer

Shifting by one place

You already know how in base ten to multiply a number by 10: add a zero to the end. So 83 × 10 = 830. This works because:

83 = 8 × 10^1 + 3 × 10^0

83 × 10 = ( 8 × 10^1 + 3 × 10^0 ) × 10

= 8 × 10^2 + 3 × 10^1

= 830

The same trick works in any base:

If a number is represented by (say) XYZ in base B, then XYZ0 represents that number times B.

Question 9

What is sixteen times 8B3?

Answer

8B30

Shifting by one place in base sixteen

Adding a 0 to the end of an integer written in base sixteen multiplies the integer by sixteen. To multiply an integer by sixteen^N, add N zeros on the right:

8B3 × 10^3 = 8B3000 (Here 10 means sixteen.)

To divide an integer represented in hexadecimal by 16, remove the rightmost digit. The result is the quotient. The removed digit is the remainder.

8B3 div sixteen = 8B (remainder 3).

Question 10

A (base 16) = ___ (base 10) = ___ (base 2)

Answer

A (base 16) = 10 (base 10) = 1010 (base 2)

Representation in base sixteen, ten, and two

Here is a chart that shows integers zero through fifteen and their positional representation using base sixteen, ten, and two.

For example: 01102 = 22 + 21 = 6ten = 6sixteen

Question 11

What is the name of this pattern of four bits, using the pattern naming scheme: 1010?

Answer

A. This is the name of the pattern the four bits make.

Base 16 representation and 4-bit pattern names

The name of the binary pattern 1010 is "A". The hex digit that corresponds to the integer represented by 10102 is also "A".

It is OK to have a pattern that has the name "A" and also to use "A" as a digit.

If a 4-bit pattern represents an integer in base two, that integer represented in base 16 is the same digit as the bit pattern name.

The name of a 4-bit pattern (regarded as an abstract pattern) is the same as the hexadecimal digit whose representation in binary is that 4-bit pattern. This is not accidental.

Question 12

Here is an integer represented in base two: 1011. What is the representation in base two of the number times sixteen?

Hint: remember that trick with appending zeros.

Answer

1011 0000. Appending four zeros multiplies the number being represented by 24.

Converting hex representation into binary representation

Convert a hexadecimal representation of an integer into an unsigned binary representation directly by replacing each hex digit with its 4-bit binary equivalent. For example:

1 A 4 4 D (Hex Representation)

0001 1010 0100 0100 1101 (Binary Representation)

Recall that:

- (In base two) Shifting left by four bits is equivalent to multiplication by sixteen.

- (In base sixteen) Shifting left by one digit is equivalent to multiplication by sixteen.

To see how this works, look at this integer represented in base two and in base sixteen:

base two base sixteen

1010 = A

Now multiply each by sixteen:

base two base sixteen

1010 0000 = A0

Groups of four bits (starting from the right) match powers of sixteen, so each group of four bits matches a digit of the hexadecimal representation. Let us rewrite the integer C6D in binary:

C6D = C × sixteen^2 + 6 × sixteen^1 + D × sixteen^0

= C × (2^4)^2 + 6 × (2^4)^1 + D × (2^4)^0

= 1100 × (2^4)^2 + 0110 × (2^4)^1 + 1101 × (2^4)^0

= 1100 × 2^8 + 0110 × 2^4 + 1101 × 1

Using the idea that each multiplication by two is equivalent to appending a zero to the right, this is:

= 1100 0000 0000 + 0110 0000 + 1101

C6D = 1100 0110 1101

Each digit of hex can be converted into a 4-bit binary number, each place of a hex number stands for a power of 2^4. It stands for a number of 4-bit left shifts.

Question 13

What is the name of the binary pattern 0001 1010 0100 0100 1101?

Answer

1A44D

Pattern name and number representation

A bit pattern that represents an integer in unsigned binary has a pattern name using hex. That pattern name is the same string of characters as the base 16 representation of the integer.

Converting between base 16 representation and base 2 representation is easy because 16 is a power of 2. Another base where this is true is base 8 (octal), since 8 is 2^3. In base 8, the digits are 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. The binary equivalents of the digits are 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, 111.

Each place in a base 8 representation corresponds to a left shift of 3 places in the bit pattern of its binary representation.

Be careful: in some computer languages (Java and C, for instance) a number written with a leading zero signifies octal. So 0644 means base eight, and 644 means base ten, and 0x644 means base sixteen.

Question 14

What is the binary equivalent of 4733 octal?

Answer

100 111 011 011

Converting between representations

With effort, you could directly translate between octal and hex notation. But it is much easier to use binary as an intermediate:

octal → binary → hexadecimal

You can convert a representation of a number in base B directly to a representation in base Y. But it is usually more convenient to use decimal or binary as an intermediate:

Base B → Decimal → Base Y

Base B → Binary → Base Y

Which intermediate to pick depends on the problem.

Question 15

Change the representation of this number from hexadecimal to octal (base 8):

0x1A4

Answer

binary

hex groups of four

0x1A4 = 0001 1010 0100 =

binary octal

ungrouped groups of three

000110100100 = 000 110 100 100 = 0644_eight

Remember to group bits starting from the right. If the left group is one or two bits short, add zero bits on the left as needed.

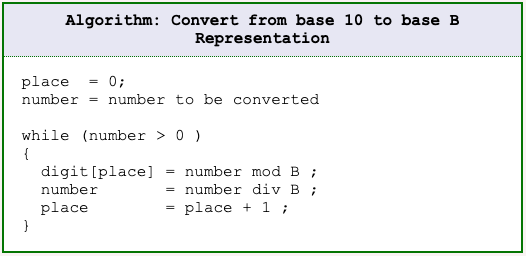

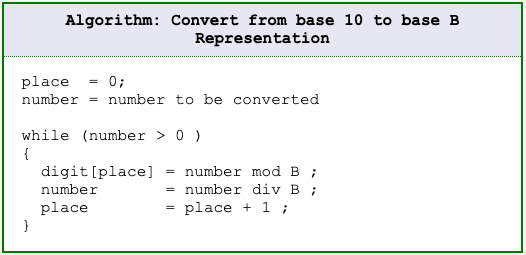

Decimal to base B

You already know how to convert from Base B to Decimal.

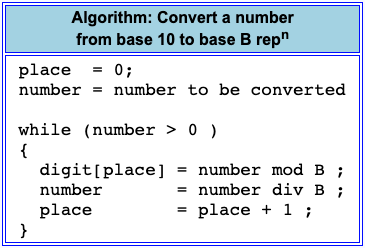

The algorithm converts number from decimal representation to base B representation.

divmeans integer division andmodmeans modulo.number div Bis how many times B goes into number.number mod Bis the left-over amount.

For example, 15 div 6 = 2 and 15 mod 6 = 3.

Here is an example: convert 5410 to hex representation. The base B is 16. The first execution of the loop body calculates digit[0] the right-most digit of the hex number.

Question 16

What is digit[ 0 ] = 54 mod 16?

What is number = 54 div 16?

Answer

54 = 16 × 3 with a remainder of 6.

digit[ 0 ] = 54 mod 16 = 6,

number = 54 div 16 = 3

Hex digits from right to left

The first execution of the loop body calculates the digit for place 0, the rightmost digit. The first execution calculates that: 5410 = 3 × 161 + 6 × 160

The 6 becomes the rightmost digit and the 3 becomes number for the next iteration.

The next iteration is for the next digit left. The calculation is 3 mod 16 = 3 and number = 3 div 16 = 0. The 3 becomes the digit, and the 0 becomes number.

Because number is now zero, the algorithm is done, and the result is 5410 = 0x36.

If you are enthused about this you might wish to use mathematical induction to prove that the algorithm is correct.

Question 17

Convert 24710 to hexadecimal.

Answer

number = 247

247 div 16 = 15 r 7 → digit[ 0 ] = 7

number = 15

15 div 16 = 0 r 15 → digit[ 1 ] = F ("15" is in base 10, "F" is the hex digit)

Result: 247_10 = 0xF7

Another conversion

To convert 247 from decimal to base 16, repeatedly divide by 16, collecting the remainders in the base 16 expression. This is shown above. Check the result by converting the base 16 expression to decimal:

0xF7 = F × sixteen + 7 × 1

= 15 × 16 + 7

= 240 + 7 = 247_10

The algorithm can be described as:

- Divide the number by the base.

- The remainder is the digit.

- The quotient becomes the number.

- Repeat.

The digits come out right to left.

Question 18

Convert 103310 to hex.

Answer

0x409

1033 div 16 = 64 r 9; digit[0] = 9

64 div 16 = 4 r 0; digit[1] = 0

4 div 16 = 0 r 4; digit[2] = 4

Decimal to base 5

The conversion algorithm works to convert a decimal representation of a number to any base. Here is a conversion of 103310 to base 5:

So 103310 = 131135 (the first digit produced is the rightmost). Check the results:

13113_5 = 1 × 5^4 + 3 × 5^3 + 1 × 5^2 + 1 × 5^1 + 3 × 5^0

= 1 × 625 + 3 × 125 + 1 × 25 + 1 × 5 + 3

= 625 + 375 + 25 + 5 + 3

= 1033_10

Question 19

Convert 10010 to base 3.

Answer

See Below.

Converting base 3 to base 7

Since the base is 3, the algorithm calls for repeatedly dividing by 3 until the number is reduced to zero.

100_ten =

100 div 3 = 33 r 1;

33 div 3 = 11 r 0;

11 div 3 = 3 r 2;

3 div 3 = 1 r 0;

1 div 3 = 0 r 1

So 100ten = 102013.

Checking the answer:

10201_3 = 1 × 3^4 + 0 × 3^3 + 2 × 3^2 + 0 × 3^1 + 1 × 3^0

= 1 × 81 + 0 × 27 + 2 × 9 + 0 × 3 + 1

= 81 + 18 + 1 = 100

To convert from a representation in base three to a representation in base seven, use base ten as an intermediate: convert from base three into base ten, then from base ten to base seven.

Question 20

What is the base 7 representation of 102013?

Answer

100 div 7 = 14 r 2;

14 div 7 = 2 r 0;

2 div 7 = 0 r 2;

So 102013 = 100ten = 2027.

Chapter quiz

Question 1

Change the representation of 10102 from base two to base ten.

- (A)

810 - (B)

910 - (C)

1010 - (D)

1110 - (E)

1210 - (F)

1410

Answer

C

Question 2

What number goes in the empty cell of the table:

- (A) 34

- (B) 48

- (C) 60

- (D) 64

- (E) 68

- (F) 72

Answer

D

Question 3

Change the representation of 1000102 from base two to base ten.

- (A)

14 - (B)

28 - (C)

32 - (D)

34 - (E)

46 - (F)

52

Answer

D

Question 4

Change the representation of 0000 11112 from base two to base ten. (Hint: you should get this instantly.)

- (A)

6 - (B)

7 - (C)

12 - (D)

15 - (E)

16 - (F)

31

Answer

D

Question 5

Change the representation of 0011 11002 from base two to base ten. (Hint: use your previous answer.)

- (A)

14 - (B)

28 - (C)

32 - (D)

60 - (E)

64 - (F)

72

Answer

D

Question 6

Say that you are using unsigned binary to represent integers with 6 bits. What range of integers can be represented?

- (A) 0 to 64

- (B) 1 to 64

- (C) 0 to 63

- (D) 1 to 128

- (E) 0 to 255

- (F) 1 to 247

Answer

C

Question 7

Change the representation of A516 from base sixteen to base ten.

- (A)

46 - (B)

165 - (C)

232 - (D)

245 - (E)

305 - (F)

1025

Answer

B

Question 8

Here is a number represented in base 16 notation: 5A3F. Write the number in unsigned binary notation.

- (A)

0101 1010 0011 1111 - (B)

1111 0011 1010 1001 - (C)

1100 1000 0111 1111 - (D)

1010 1001 0011 1000 - (E)

1011 0001 0000 1110 - (F)

1110 1011 1011 1001

Answer

A

Question 9

Convert the representation of the following from base 16 to base 8: 0x37A.

- (A)

011 111 1010 - (B)

0772 - (C)

001 101 111 010 - (D)

1572 - (E)

8214 - (F)

7426

Answer

D

Question 10

Represent 2710 in base 2.

- (A)

101101 - (B)

10110 - (C)

1011 - (D)

11011 - (E)

101101 - (F)

100110

Answer

D

Question 11

Convert 3045 from base 5 to base 10.

- (A)

15 - (B)

23 - (C)

27 - (D)

32 - (E)

79 - (F)

83

Answer

E

Question 12

Convert 3045 from base 5 to base 2 (use your previous answer).

- (A) 1100 1001

- (B) 0110 0100

- (C) 0010 1000

- (D) 1000 1100

- (E) 1010 1011

- (F) 0100 1111

Answer

F

Question 13

Write the unsigned binary number 0010 1110 in hexadecimal representation

- (A)

0232 - (B)

2F - (C)

3E - (D)

07 - (E)

2E - (F)

FF

Answer

E

Question 14

Write the unsigned binary number 000 101 110 in octal representation.

- (A)

022 - (B)

023 - (C)

013 - (D)

122 - (E)

056 - (F)

023

Answer

E

Question 15

Write the unsigned binary number 000 101 110 in decimal representation.

- (A)

26 - (B)

46 - (C)

52 - (D)

64 - (E)

122 - (F)

131

Answer

B

Binary Addition and Two's Complement Representation

Digital computers use bit patterns to represent many types of data. Various operations can be performed on data. Computers perform operations on bit patterns. With a good representation scheme, bit patterns represent data and bit pattern manipulations represent operations on data.

An important example of this is the Binary Addition Algorithm, where two bit patterns representing two integers are manipulated to create a third pattern which represents the sum of the integers.

Chapter Topics:

- Single-bit Binary Addition Table

- Binary Addition Algorithm

- Addition in Hexadecimal Representation

- Sign-magnitude Representation

- Two's complement Representation

- Overflow detection in unsigned binary

- Overflow detection in two's complement binary

Most processor chips implement the Binary Addition Algorithm in silicon as part of their arithmetic logic unit. In a course in digital electronics you will study the hardware details of its implementation. This chapter discusses the fundamentals of the algorithm.

Question 1

Compute the following. Give the answer in binary notation.

0 + 0 = ?

0 + 1 = ?

1 + 0 = ?

1 + 1 = ?

Answer

In binary:

0 + 0 = 0

0 + 1 = 1

1 + 0 = 1

1 + 1 = 10

The binary addition algorithm

The binary addition algorithm is a bit-pattern manipulation procedure that is built into the hardware of (nearly) all computers. All computer scientists and computer engineers know it.

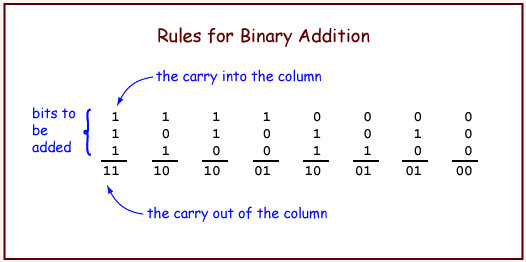

Let us start by adding 1-bit integers. The operation is performed on three bits. Arrange the bits into a column. The bit at the top of the column is called the "carry into the column". The operation produces a two-bit result. The left bit of the result is called the "carry out of the column".

To add two 1-bit (representations of) integers: Count the number of ones in a column and write the result in binary. The right bit of the result is placed under the column of bits. The left bit is called the "carry out of the column". The table shows the outcomes with all possible operands.

Question 2

Perform the following additions:

1 0 1

0 1 1

1 0 0

____ _____ _____

Answer

1 0 1

0 1 1

1 0 0

____ _____ _____

10 01 10

N-bit binary addition algorithm

Adding a column of bits is as easy as counting. It is also easy to do electronically. When you take a course in digital logic you will probably build a circuit to do it.

Now let us look at the full, n-bit, binary addition algorithm. The algorithm takes two operands and produces one result. An operand is the data that an algorithm operates on.

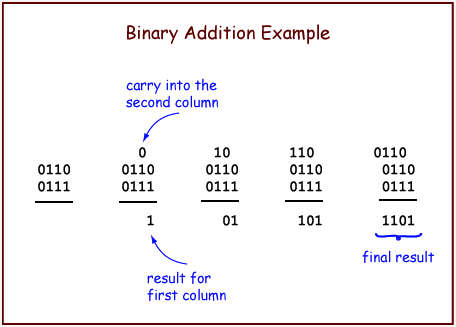

To add two N-bit (representations of) integers: Proceed from right-to-left, column-by-column, until you reach the left-most column. For each column, perform 1-bit addition. Write the carry-out of each column above the column to its left. The bit is the left column's carry-in.

The example adds two 4-bit operands. The initial conditions are shown on the left. First, add up the bits in the right-most column. There is no carry-in to this column, so all you need to do is count the bits. The result is 1 with a carry of 0. Write the 1 as the result for the column, and put the carry above the next column. The picture shows this in blue. Continue right-to-left through the columns until all columns have been added. The carry-out of the right-most column should not go into the sum, but should be written to the right of the other carry bits.

Question 3

Confirm that this addition is correct. (1) Check that the binary addition algorithm was performed correctly by checking the left column, then (2) translate the binary operands into decimal to fill the blanks in the right column, and then (3) verify that the decimal addition in the right column gives the same sum.

0110 = ___ (base 10)

0111 = ___ (base 10)

______

1101 = ___ (base 10)

Hopefully, the binary result in the bottom row will represent the same integer as the decimal result in the bottom row.

Answer

0110 = 6 (base 10)

0111 = 7 (base 10)

______

1101 = 13 (base 10)

A longer example

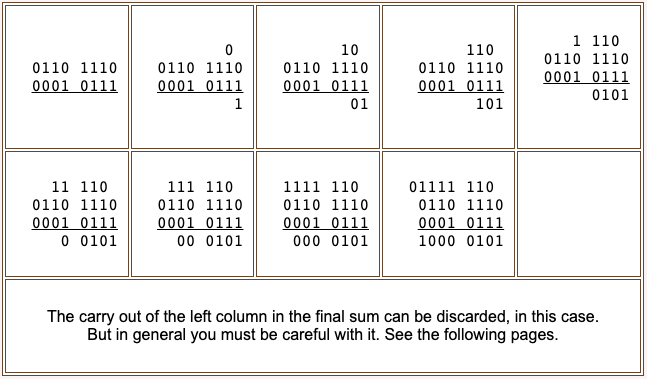

Here is another example. Observe that the binary addition algorithm is the same algorithm you use with ordinary base ten addition, except now the base two addition table is used for each column.

Check the answer by converting to decimal representation and doing the addition in that base (the same numbers are being added, but now represented in a different way, so the sum is the same.)

01111 110

0110 1110 = 110 (base 10)

+ 0001 0111 = 23 (base 10)

_________

1000 0101 = 133 (base 10)

Question 4

Do the following:

10

+ 01

_____

Answer

00

10

+ 01

_____

11

This is another case where the answer fits into the same number of bits as the numbers to add.

Details, details

Here are some details:

Usually the operands and the result have a fixed number of bits (usually 8, 16, 32, or 64). These are the sizes that processors use to represent integers.

To keep the result the same size as the operands, you may have to include zero bits in some of the leftmost columns.

Compute the carry-out of the leftmost column, but don't write it as part of the answer (because there is no room if you have a fixed number of bits.)

When the operands are represented using the unsigned binary scheme (the base two representation scheme discussed in the last two chapters) a carry-out of 1 from the leftmost column means the sum does not fit into the fixed number of bits. This is called Overflow.

When the operands are represented using the two's complement scheme (which will be described at the end of this chapter), then a carry-out of 1 from the leftmost column is not necessarily overflow.

Integers may be represented using a scheme called unsigned binary or using a scheme called two's complement binary. The binary addition algorithm is used with both schemes, but to interpret the result you need to know what scheme is being used. Overflow is detected in different ways with each scheme (see details 4 and 5, above.)

Question 5

The MIPS32 chip has 32-bit registers. What do you think is the usual size of the operands when binary addition is performed?

Answer

32 bits.

Overflow detection

Here is an addition problem using 4-bit operands:

1111

0111

1001

------

0000

Overflow happened

Two four-bit numbers are added, but the sum does not fit in four bits. If we were using five bits the sum would be 1 0000. But with four bits there is no room for the left-most "1". Because the carry out from the most significant column of the sum is "1", the 4-bit result is not valid. The column is called the most significant column because it corresponds to the highest power of two. The bits in the leftmost columns are called the most significant bits or the high-order bits.

The electronic circuits of a processor can easily detect overflow of unsigned binary addition by checking if the carry-out of the leftmost column is a zero or a one. A program might branch to an error handling routine when overflow is detected.

Question 6

Add these unsigned numbers, represented in eight bits. Determine if overflow occurs.

0010 1100

0101 0101

-----------

Answer

0 1111 100

0010 1100

0101 0101

------------

1000 0001

(No overflow)

More practice

Practice performing this algorithm until you can do it mechanically, like a computer. Detect overflow by looking at the carry-out of the leftmost column. You don't need to convert the representation to decimal.

Question 7

Add these numbers, represented in eight bits. Determine if overflow occurs.

0110 1100

1001 1111

-----------

Answer

1 1111 100

0110 1100

1001 1111

-----------

0000 1011

(overflow detected)

Hex addition

Sometimes you need to add two numbers represented in hexadecimal. Usually it is easiest to convert to binary representation to do the addition. Then convert back to hexadecimal.

Remember that converting representations from hexadecimal to binary is easily done by using the equivalence of hex digits and bit pattern names.

Question 8

Perform the following addition:

0F4A

420B

------

Answer

1 11 1 1

0F4A → 0000 1111 0100 1010

420B → 0100 0010 0000 1011

---- -------------------

0101 0001 0101 0101 → 0x5155

Additional additional practice

In the answer (above), the carry out of zero from the left column indicates that overflow did not happen.

Sometimes a hex addition problem is easy enough to do without converting to binary:

014A

4203

------

434D

It may be helpful to use your digits (fingers) in doing this: to add A+3 extend three fingers and count "A... B... C... D".

Question 9

Compute the following sum using 8 bits. Is there overflow?

1101 0010

0110 1101

-----------

Answer

0011 1111

11

1101 0010 210_(10)

0110 1101 109_(10)

----------

0011 1111 63_(10)

The carry bit of 1 indicates overflow.

Yet more additional practice

The correct application of the "Binary Addition Algorithm" sometimes gives incorrect results (because of overflow). With paper-and-pencil arithmetic, overflow is not a problem because you can use as many columns as needed.

Correct unsigned binary addition: When the "Binary Addition Algorithm" is used with unsigned binary integer representation: The result is CORRECT only if the CARRY OUT of the high order column is ZERO.

But digital computers use fixed bit-lengths for integers, so overflow is possible. For instance some processors represent integers in 8, 16, or 32 bits. When 8-bit operands are added, overflow is certainly possible. Our MIPS processor uses 32-bit integers, but even with them, overflow is possible.

Question 10

Compute the following sum using 8 bits:

0000 0001

1111 1111

Answer

11111 111

0000 0001 1_(10)

1111 1111 255_(10)

-----------

0000 0000 00_(10)

The carry bit of 1 out of the high order column (leftmost) indicates an overflow.

Negative integers

Unsigned binary representation can not be used to represent negative integers. With paper and pencil numbers, a number is made negative by putting a negative sign in front of it: 2410 negated = -2410. You might hope to do the same with binary integers:

0001 1000 negated = -0001 1000 ???

Unfortunately, you can't put a negative sign in front of a bit pattern in computer memory. Memory holds only patterns of 0's and 1's. Somehow negative integers must be represented using bit patterns. But this is certainly possible. Remember those advantages of binary?

- Easy to build.

- Unambiguous signals (hence noise immunity).

- Can be copied flawlessly.

- Anything that can be represented with symbols can be represented with patterns of bits.

If we can represent negative integers with paper and pencil (thus using symbols) we certainly can represent negative integers with patterns of bits.

Question 11

Let us say that you need to represent an equal number of positive and negative integers in eight bits. How many negative numbers can represented? How many positive numbers?

Just for fun, can you think of a way to do this? Get out some scratch paper and scratch for a while with eight-bit patterns.

Answer

Since there are 256 possible bit patterns with 8 bits, there could be 128 positive and 128 negative integers.

You may have thought of the sign-magnitude method, discussed below.

Sign-magnitude representation

There are many schemes for representing negative integers with patterns of bits. One scheme is sign-magnitude. It uses one bit (usually the leftmost) to indicate the sign. "0" indicates a positive integer, and "1" indicates a negative integer. The rest of the bits are used for the magnitude of the number. So -2410 is represented as:

1001 1000

The sign "1" in the left-most column means negative

The magnitude is 24 (in 7-bit binary)

Question 12

With 8-bit sign-magnitude representation, what positive integers can be represented and what negative integers can be represented?

Answer

-12710 ... 0 ... +12710Problems with sign-magnitude

There are problems with sign-magnitude representation of integers. Let us use 8-bit sign-magnitude for examples.

The leftmost bit is used for the sign, which leaves seven bits for the magnitude. The magnitude uses 7-bit unsigned binary, which can represent 010 (as 000 0000) up to 12710 (as 111 1111). The eighth bit makes these positive or negative, resulting in -12710, ... -0, 0, ... 12710.

One pattern corresponds to "minus zero", 1000 0000. Another corresponds to "plus zero", 0000 0000.

There are several problems with sign-magnitude. It works well for representing positive and negative integers (although the two zeros are bothersome). But it does not work well in computation. A good representation method (for integers or for anything) must not only be able to represent the objects of interest, but must also support operations on those objects.

This is what is wrong with Roman Numerals: they can represent positive integers, but they are very poor when used in computation.

Question 13

Can the "binary addition algorithm" be used with sign-magnitude representation? Try adding +16 with -24:

0001 0000 16

1001 1000 -24

----------- ----

Answer

1

0001 0000 16

1001 1000 -24

----------- ----

1010 1000 -40 (wrong!)

Patterns that add up to zero

The "binary addition algorithm" does NOT work with sign-magnitude. There are algorithms that do work with sign-magnitude, and some early computers were built to use them. (And other computers were built using other not-ready-for-prime-time algorithms). It took several years of experience for computer science to decide that a better way had to be found.

There is a better way. Recall a question and its answer from several pages ago:

11111 111

0000 0001 = 1_(10)

1111 1111 = ?

-----------

0000 0000 = 0_(10)

Question 14

A number added to one results in a zero. What could that number be?

Answer

Might be minus one.

Patterns that add to zero

Minus one added to plus one gives zero. So if a particular bit pattern results in the pattern that represents zero when added to one, it can represent minus one.

11111 111

0000 0001 = 1_(10)

1111 1111 = -1

----------- ----

0000 0000 = 0_(10)

There is a carry out of one from the high order column, but that is fine in this situation. The "binary addition algorithm" correctly applied gives the correct result in the eight bits. Look at another interesting case:

11111 11

0000 1110 = 14_(10)

1111 0010 = ?

-----------

0000 0000 = 0_(10)

Question 15

A number added to 14_(10) results in a zero. What could that number be?

Answer

Might be -14.

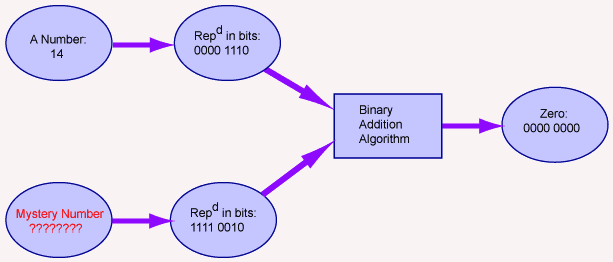

Negative fourteen

The pattern 1111 0010 might be a good choice for "negative fourteen". In the picture, the only good choice for "Mystery Number" is negative fourteen.

For every bit pattern of N bits there is a corresponding bit pattern of N bits which produces an N-bit zero when the two patterns are used as operands for the binary addition algorithm. Each pattern can be thought of as representing the negative of the number that is represented by the other pattern.

Question 16

Find the 8-bit pattern that gives eight zero-bits when added to the bit pattern for 610. (Hint: start at the right column, figure out what the ? has to be in each column, and work your way left.)

0000 0110 = 6_(10)

???? ???? = -6_(10)

————————— ————

0000 0000 0_(10)

Answer

0000 0110 = 6_(10)

1111 1010 = -6_(10)

————————— ————

0000 0000 0_(10)

Two's complement

This representation scheme is called two's complement. It is one of many ways to represent negative integers with bit patterns. But it is now the nearly universal way of doing this. Integers are represented in a fixed number of bits. Both positive and negative integers can be represented. When the pattern that represents a positive integer is added to the pattern that represents the negative of that integer (using the "binary addition algorithm"), the result is zero. The carry out of the left column is discarded.

Here is how to figure out which bit-pattern gives zero when added (using the "binary addition algorithm") to another pattern.

How to Construct the Negative of an Integer in Two's Complement: Start with an N-bit representation of an integer. To calculate the N-bit representation of the negative integer:

- Reflect each bit of the bit pattern (change 0 to 1, and 1 to 0).

- Add one.

This process is called forming the two's complement of N. An example:

The positive integer: 0000 0001 ( one )

Reflect each bit: 1111 1110

Add one: 1111 1111 ( minus one )

Question 17

Fill in the blanks:

The positive integer: 0000 0110 (6_10)

Reflect each bit:

Add one: (-6_10)

Answer

The positive integer: 0000 0110 (6_10)

Reflect each bit: 1111 1001

Add one: 1111 1010 (-6_10)

The result is the same representation for minus six as we figured out before.

Negative six again

Here is what is going on: When each bit of a pattern is reflected then the two patterns added together make all 1's. This works for all patterns:

0110 1010 pattern

1001 0101 pattern reflected

-----------

1111 1111 all columns filled

Adding one to this pattern creates a pattern of all zero's:

11111 111 row of carry bits

1111 1111 all columns filled

0000 0001 one

-----------

0000 0000

The negation algorithm makes use of the above trick. Three patterns added together result in a zero. If one pattern represents an integer, then the sum of the other two patterns represents the negative of the integer.

pattern + pattern reflected + one = all zeros

pattern + (pattern reflected + one ) = all zeros

pattern + (two's complement of pattern) = all zeros

Don't be too upset if the above is confusing. Mostly all you need is to get used to this stuff. Of course, this takes practice.

Question 18

What is the two's complement of 0100 0111?

Answer

| reflect | add one | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

0100 0111 | → | 1011 1000 | → | 1011 1001 |

It is always a good idea to check your results:

11111 111

0100 0111

+ 1011 1001

-----------

0000 0000

Two's complement integers

What is the two's complement of zero?

zero = 0000 0000

reflect = 1111 1111

add one = 0000 0000

Using the algorithm with the representation for zero results in the representation for zero. This is good. Usually "minus zero" is regarded as the same thing as "zero". Recall that with the sign-magnitude method of representing integers there where both "plus" and "minus" zero.

What integers can be represented in 8-bit two's complement? Two's complement represents both positive and negative integers. So one way to answer this question is to start with zero, check that it can be represented, then check one, then check minus one, then check two, then check minus two ... Let's skip most of those steps and check 12710:

127 = 0111 1111 check: 0111 1111

reflect = 1000 0000 1000 0001

-----------

add one = 1000 0001 0000 0000

-127 = 1000 0001

Question 19

Now try to compute the negative of 128ten.

128 = 1000 0000

reflect = _________

add one = _________

Answer

128 = 1000 0000

reflect = 0111 1111

add one = 1000 0000 ??????

Range of integers with 2's complement

It looks like +128 and -128 are represented by the same pattern. This is not good. A non-zero integer and its negative can't both be represented by the same pattern. So +128 can not be represented in eight bits. The maximum positive integer that can be represented in eight bits is 12710.

What number is represented by 1000 0000? Add the representation of 12710 to it:

1000 0000 = ?

0111 1111 = 127_(10)

-----------

1111 1111 = -1_(10)

A good choice for ? is -12810. Therefore 1000 0000 represents -12810. Eight bits can be used to represent the numbers -12810 ... 0 ... +12710.

Range of N bit 2's complement:

For example, the range of integers that can be represented in eight bits using two's complement is:

Notice that one more negative integer can be represented than positive integers.

Question 20

How many integers are there in the range -128 ... 0 ... +127?

How bit patterns can be formed with 8 bits?

Answer

256

Every pattern of the 256 patterns has been assigned an integer to represent.

The "sign bit"

The algorithm that creates the representation of the negative of an integer works with both positive and negative integers. Start with N and form its two's complement: you get -N. Now complement -N and you get the original N.

0110 1101 reflect → 1001 0010 add one → 1001 0011

1001 0011 reflect → 0110 1100 add one → 0110 1101

With N-bit two's comp representation, the high order bit is "0" for positive integers and "1" for negative integers. This is a fortunate result. The high order bit is sometimes called the sign bit. But it is not really a sign (it does not play a separate role from the other bits). It takes part in the "binary addition algorithm" just as any bit.

Question 21

Does the following four-bit two's complement represent a negative or a positive integer?

1001

Answer

negative

The sign of the four bits

Be sure that you understand this: It is by happy coincidence that the high order bit of a two's complement integer is 0 for positive and 1 for negative. But, to create the two's complement representation of the negative of a number you must "reflect, add one". Changing the sign bit by itself will not work.

To convert N bits of two's complement representation into decimal representation:

- If the integer is negative, complement it to get a positive integer.

- Convert (positive) integer to decimal (as usual).

- If the integer was originally negative, put "-" in front of the decimal representation.

The number represented by 1001 is negative (since the "sign bit" is one), so complement:

1001 → 0110 + 1 → 0111

Convert the result to decimal: 0111 = 710. Add a negative sign: -710. So (in 4-bit two's complement representation) 1001 represents -710.

Question 22

What is the decimal representation of this 8-bit two's complement integer: 1001 1111

Answer

First note that the "sign bit" is set, so the integer is negative. Then find the positive integer:

1001 1111 reflect → 0110 0000 add one → 0110 0001

convert to decimal → 2^6 +2^5 + 1 = 97_(10)

put sign in front → -97_(10)

Overflow detection in 2's complement

The binary addition algorithm can be applied to any pair of bit patterns. The electronics inside the microprocessor performs this operation with any two bit patterns you send it. You send it bit patterns. It does its job. It is up to you (as the writer of the program) to be sure that the operation makes sense.

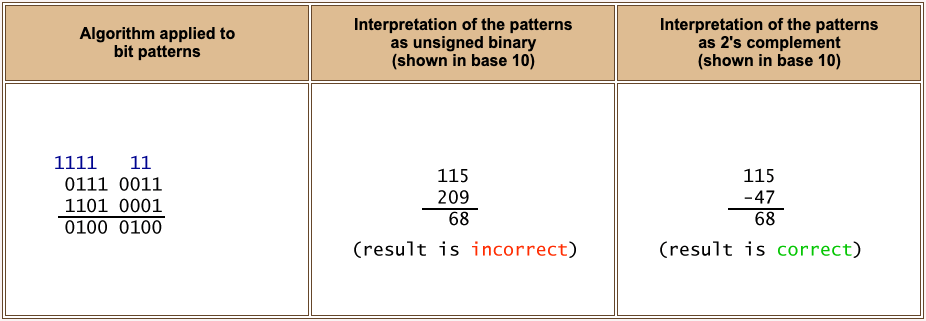

Overflow is detected in a different way for each representation scheme. In the following exhibit the "binary addition algorithm" is applied to two bit patterns. Then the results are looked at as unsigned binary and then as two's complement:

The "binary addition algorithm" was performed on the operands. The result is either correct or incorrect depending on how the bit patterns are interpreted. If the bit patterns are regarded as unsigned binary integers, then overflow happened. If the bit patterns are regarded as two's comp integers, then the result is correct.

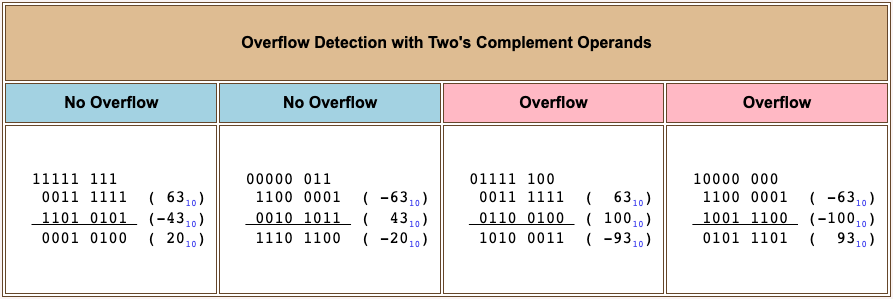

Correct Two's Complement Addition: When the "binary addition algorithm" is used with operands in two's complement representation: The result is correct if the carry INTO the high order column equals the carry OUT OF the high order column. The carry bits can both be zero or both be one.

Question 23

If the bit patterns in the above addition problem are regarded as two's complement, is the result correct?

(correct result: ) The carry into the left column is the SAME as the carry out. (incorrect result:) The carry into the left column is DIFFERENT from the carry out.

Answer

(correct result:) The carry into the left column is the SAME as the carry out.

Carry in == carry out

With two's complement representation the result of addition is correct if the carry into the high order column is the same as the carry out of the high order column. The carry can be one or zero. Overflow is detected by comparing two bits, an easy thing to do with electronics. Here are some more examples:

Question 24

Perform the "binary addition algorithm" on the following 8-bit two's complement numbers. Is the result correct or not?

1011 1101

1110 0101

-----------

Answer

The result is correct.

11111 1 1

1011 1101

1110 0101

-----------

1010 0010

Electronically checking overflow

Look at the answer: since the carry into the high order column is the same as the carry out of the high order column, the result is correct. We don't need to figure out what decimal numbers the patterns represent.

11111 1 1

1011 1101

1110 0101

-----------

1010 0010

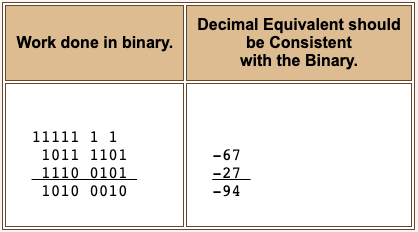

The electronics of a computer determine if a calculation is correct by using a simple circuit that tests the equality of the carry-in bit and the carry-out bit of the high order column. There is no other means of looking at a calculation to see if it is correct. However, when you do a calculation with paper and pencil you can check your work by translating the operands and results into decimal:

Of course, the computer has no independent means of "checking its result." All it can do is look at the carry bits into and out of the high order column.

Question 25

Can the binary addition algorithm be used with patterns that represent negative integers?

Answer

Yes. The previous example just did that.

Subtracting an integer X from Y is the same as adding -X to Y.

Subtraction in two's complement

The binary addition algorithm is used for subtraction and addition. To subtract two numbers represented in two's complement, form the two's complement of the number to be subtracted and then add. Overflow is detected as usual.

Question 26

Subtract 0001 1011 from 0011 0001.

Is the result correct or not?

Answer

0001 0110

(correct)

Multi-purpose algorithm

The number to be subtracted is negated by the usual means (reflect the bits, add one):

0001 1011 → 1110 0101

Then the "binary addition algorithm" is used:

11100 001

0011 0001 = 49_(10)

1110 0101 = -27_(10)

————————— ————

0001 0110 22_(10)

Since the carry into the most significant column is the same as the carry out of that column, the result is correct. We are getting quite a bit of use out of the "binary addition algorithm". It is used to:

- Add integers represented in unsigned binary.

- Add integers represented in two's complement binary.

- Subtract integers represented in two's complement binary.

It can't be used directly to subtract integers represented in unsigned binary. (If both unsigned integers are small enough, the one being subtracted can be represented as a two's complement negative, and then the algorithm can be used.)

Question 27

Subtract 0101 1001 from 0010 0101.

Is the result correct or not?

Answer

1100 1100

(correct)

More practice subtraction

The number to be subtracted is negated by the usual means (reflect the bits, add one):

0101 1100 → 1010 0111

Then the "binary addition algorithm" is used:

00100 111

0010 0101 = 37_(10)

1010 0111 = -89_(10)

————————— ————

1100 1100 -52_(10)

Since the carry into the most significant column is the same as the carry out of that column the result is correct. The answer came out negative, but that is fine.

Computer scientists and computer engineers are expected to understand the binary addition algorithm. Practice it. Or you can change your major to Art History (and leave the high paying jobs to the rest of us). Here is another problem:

Question 28

Subtract 0101 1001 from 1110 0101.

Is the result correct or not?

Answer

1000 1100

(correct)

More and more practice subtraction

The number to be subtracted is negated by the usual means, as in the previous problem. Then the "binary addition algorithm" is used:

11100 111

1110 0101 = -27_(10)

1010 0111 = -89_(10)

————————— ————

1000 1100 -116_(10)

Since the carry into the most significant column is the same as the carry out of that column the result is correct. The answer came out negative, but that is fine.

A computer does several million of these operations per second. Surely you can do another one? How about if I give you two whole seconds?

Question 29

Subtract 0111 1000 from 1011 0000.

Is the result correct or not?

Answer

0011 1000

(incorrect)

The integer to be subtracted is complemented...

0111 1000 → 1000 0111 + 1 → 1000 1000

...then added to the other:

10000 000

1011 0000 = - 80_(10)

1000 1000 = -120_(10)

————————— ————

0011 1000 +56_(10) ???

Since the carry into the most significant column is NOT the same as the carry out, the result is not correct.

Chapter quiz

Question 1

In the following one-bit wide addition, what are the result R and the carry, C?

C0

0

1

--

R

- (A)

C=0;R=0 - (B)

C=0;R=1 - (C)

C=1;R=0 - (D)

C=1;R=1

Answer

B

Question 2