Algorithmic Thinking

Big O Notation and Computational Complexity

Computational Complexity

As noted on the Wiki page for computational complexity:

In computer science, the computational complexity or simply complexity of an algorithm is the amount of resources required to run it. Particular focus is given to time and memory requirements.

As the amount of resources required to run an algorithm generally varies with the size of the input, the complexity is typically expressed as a function , where is the size of the input and is either the worst-case complexity (the maximum of the amount of resources that are needed over all inputs of size ) or the average-case complexity (the average of the amount of resources over all inputs of size ).

- Time complexity is generally expressed as the number of required elementary operations on an input of size , where elementary operations are assumed to take a constant amount of time on a given computer and change only by a constant factor when run on a different computer.

- Space complexity is generally expressed as the amount of memory required by an algorithm on an input of size

Both kinds of complexities are often expressed asymptotically using big O notation, such as , , , , etc., where is a characteristic of the input influencing either complexity.

The idea behind big O notation (in terms of time complexity)

Goal of big O notation: Express the runtime of a program in terms of how quickly it grows relative to the input, as the input gets arbitrarily large.

Here's a modest breakdown of this description:

- how quickly the runtime grows: It's hard to pin down the exact runtime of an algorithm. It depends on the speed of the processor, what else the computer is running, etc. So instead of talking about the runtime directly, we use big O notation to talk about how quickly the runtime grows. And we measure this using a "loose form of math" (i.e., approximate or asymptotic analysis) where the focus is on what is basically happening ...

- relative to the input: If we were measuring our runtime directly, we could express our speed in seconds. Since we're measuring how quickly our runtime grows, we need to express our speed in terms of ... something else. With Big O notation, we use the size of the input, which we call "". So we can say things like the runtime grows "on the order of the size of the input" (i.e., ) or "on the order of the square of the size of the input" (i.e., ).

- as the input gets arbitrarily large: Our algorithm may have steps that seem expensive when is small but are eclipsed eventually by other steps as gets huge. For big O analysis, we care most about the stuff that grows fastest as the input grows, because everything else is quickly eclipsed as gets very large. (If you know what an asymptote is, you might see why "big O analysis" is sometimes called "asymptotic analysis.")

Some examples

There are three examples below that include functions which run in , , and time or constant, linear, and quadratic time, respectively.

Function that runs in constant time:

Consider the following function that runs in time (or "constant time") relative to its input:

function printFirstItem(items) {

console.log(items[0]);

}

The input array could be 1 item or 1,000 items, but this function would still just require one "step", namely the step of accessing the first item of an array and then printing it to stdout; as we will see, the operation of accessing an element of an array is a constant-time operation.

Function that runs in linear time:

Consider the following function that runs in time (or "linear time") relative to its input:

function printAllItems(items) {

items.forEach(item => {

console.log(item);

});

}

If the array has 10 items, we have to print 10 times. If it has 1,000 items, we have to print 1,000 times.

Function that runs in quadratic time:

Consider the following function that runs in time (or "quadratic time") relative to its input:

function printAllPossibleOrderedPairs(items) {

items.forEach(firstItem => {

items.forEach(secondItem => {

console.log(firstItem, secondItem);

});

});

}

Here we're nesting two loops. If our array has items, then our outer loop runs times and our inner loop runs times for each iteration of the outer loop, giving us total prints. Thus this function runs in time (or "quadratic time"). If the array has 10 items, we have to print 100 times. If it has 1,000 items, we have to print 1,000,000 times.

Drop the constants

This is one of the reasons why big O is fun, cool, and powerful. When you're calculating the big O complexity of something, you just throw out the constants like so:

function printAllItemsTwice(items) {

items.forEach(item => {

console.log(item);

});

items.forEach(item => {

console.log(item);

});

}

This is which we just call . Something like

function printFirstItemThenFirstHalfThenSayHi100Times(items) {

// O(1)

console.log(items[0]);

// ??

const middleIndex = Math.floor(items.length / 2);

let index = 0;

// O(n/2)

while (index < middleIndex) {

console.log(items[index]);

index++;

}

// O(100)

for (let i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

console.log('hi');

}

}

The above is which we just call .

Why can we get away with this? For big O notation we're looking at what happens as grows and gets arbitrarily large. As gets really big, adding 100 or dividing by 2 has a decreasingly significant effect. This can be mathematically formalized but this is enough for right now.

Drop the less significant terms

The following is loosely based on the end behavior for polynomials, namely that the end behavior of a polynomial takes on the behavior of the term with largest positive exponent. It dominates in the long run.

For example:

function printAllNumbersThenAllPairSums(numbers) {

// O(n)

numbers.forEach(number => {

console.log(number);

});

// O(n^2)

numbers.forEach(firstNumber => {

numbers.forEach(secondNumber => {

console.log(firstNumber + secondNumber);

});

});

}

Our runtime here is which we just call . Even if our runtime were , it would still be .

Similarly:

- is

- is

Again, we can get away with this because the less significant terms quickly become, well, less significant as gets big.

You are usually considering what happens in the "worst case"

Often this "worst case" stipulation is implied. But sometimes you can impress your interviewer by saying it explicitly. Sometimes the worst case runtime is significantly worse than the best case runtime:

function contains(haystack, needle) {

// Does the haystack contain the needle?

for (let i = 0; i < haystack.length; i++) {

if (haystack[i] === needle) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

Here we might have 100 items in our haystack, but the first item might be the needle, in which case we would return in just 1 iteration of our loop. In general we'd say this is runtime and the "worst case" part would be implied. But to be more specific we could say this is worst case and best case runtime. For some algorithms we can also make rigorous statements about the "average case" runtime.

Space complexity: the final frontier

Sometimes we want to optimize for using less memory instead of (or in addition to) using less time. Talking about memory cost (or "space complexity") is very similar to talking about time cost. We simply look at the total size (relative to the size of the input) of any new variables we're allocating.

The following function takes space (we use a fixed number of variables):

function sayHiNTimes(n) {

for (let i = 0; i < n; i++) {

console.log('hi');

}

}

And the following function takes space (the size of hiArray scales with the size of the input):

function arrayOfHiNTimes(n) {

const hiArray = [];

for (let i = 0; i < n; i++) {

hiArray[i] = 'hi';

}

return hiArray;

}

Usually when we talk about space complexity, we're talking about additional space, so we don't include space taken up by the inputs. For example, this function takes constant space even though the input has items:

function getLargestItem(items) {

let largest = -Number.MAX_VALUE;

items.forEach(item => {

if (item > largest) {

largest = item;

}

});

return largest;

}

Sometimes there's a tradeoff between saving time and saving space, so you have to decide which one you're optimizing for. And that's what most interviews boil down to: You are assessed on your ability to size up a situation and evaluate what tradeoffs there may be and then explain your decisions. This is really what's going on when you analyze a quick coding problem: What data structure will optimize performance for what you have decided is most important? Etc.

Big O analysis is awesome and groovy except for when it's not

You should make a habit of thinking about the time and space complexity of algorithms as you design them. Before long this will become second nature, allowing you to see optimizations and potential performance issues right away. Asymptotic analysis is a powerful tool, but wield it wisely. Big O ignores constants, but sometimes the constants matter. If we have a script that takes 5 hours to run, then an optimization that divides the runtime by 5 might not affect big O, but it still saves you 4 hours of waiting.

Beware of premature optimization. Sometimes optimizing time or space negatively impacts readability or coding time. For a young startup it might be more important to write code that's easy to ship quickly or easy to understand later, even if this means it's less time and space efficient than it could be.

But that doesn't mean startups don't care about big O analysis. A great engineer (startup or otherwise) knows how to strike the right balance between runtime, space, implementation time, maintainability, and readability.

You should develop the skill to see time and space optimizations, as well as the wisdom to judge if those optimizations are worthwhile.

Data Structures

To really understand how data structures work, we're going to derive each of the ones listed below from scratch and do so by starting with bits (see this list of data structures for more that are not listed immediately below):

- Random Access Memory

- Binary Numbers

- Fixed-Width Integers

- Arrays

- Strings

- Pointers

- Dynamic Arrays

- Linked Lists

- Hash Tables

Random Access Memory (RAM)

When a computer is running code, it needs to keep track of variables (numbers, strings, arrays, etc.). Variables are stored in random access memory (RAM). We sometimes call RAM "working memory" or just "memory."

RAM is not where mp3s and apps get stored. In addition to "memory," your computer has storage (sometimes called "persistent storage" or "disk"). While memory is where we keep the variables our functions allocate as they crunch data for us, storage is where we keep files like mp3s, videos, Word documents, and even executable programs or apps. Memory (or RAM) is faster but has less space, while storage (or "disk") is slower but has more space. A modern laptop might have ~500GB of storage but only ~16GB of RAM.

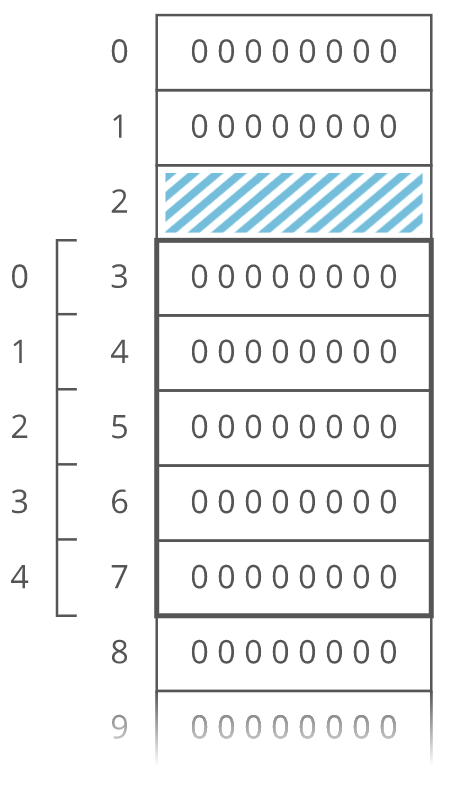

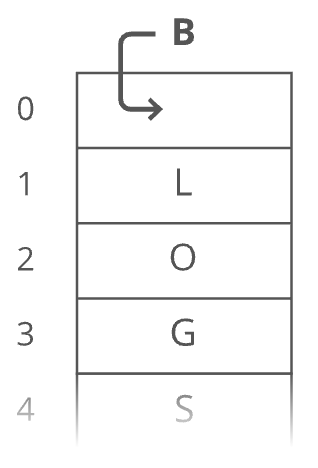

Think of RAM like a really tall bookshelf with a lot of shelves. Like, billions of shelves:

It just keeps going down. Again, picture billions of these shelves. But now picture that the shelves are numbered:

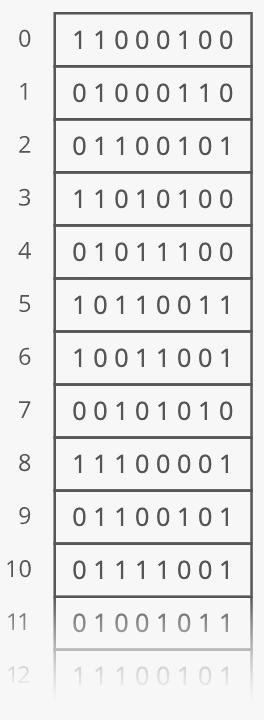

The number associated with each shelf is called the shelf's address. Each shelf holds 8 bits, where a single bit can be thought of as a tiny electrical switch that can be turned "on" or "off", but instead of calling it "on" or "off" we encode these meanings with the numbers 1 and 0, respectively. A unit of 8 bits taken together is called a byte. Each "RAM shelf" has one byte (i.e., 8 bits) of storage:

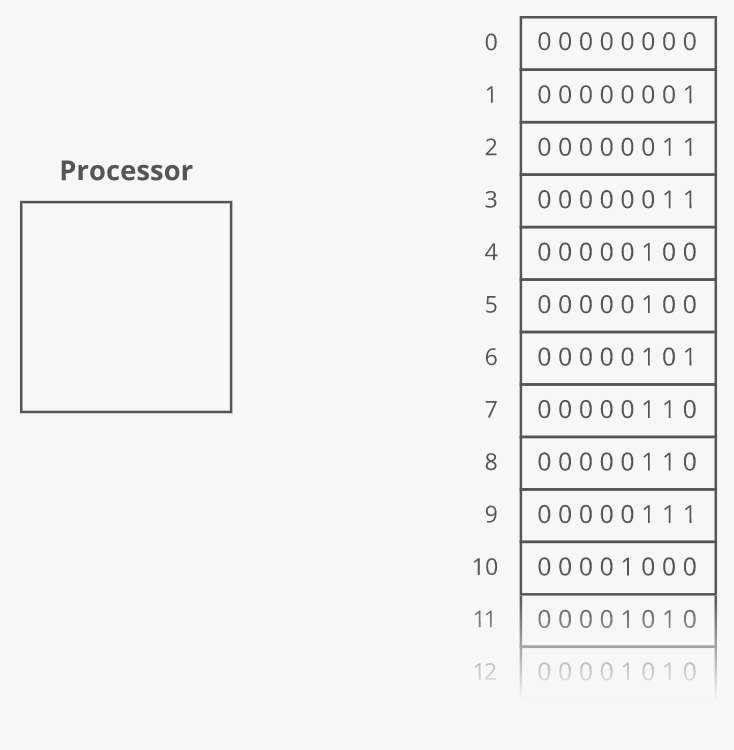

The RAM bookshelf by itself, with all its shelves, does not do anything--the workhorse for your computer is the processor(s). From the processor Wiki article:

In computing, a processor or processing unit is a digital circuit which performs operations on some external data source, usually memory or some other data stream. It typically takes the form of a microprocessor, which can be implemented on a single metal–oxide–semiconductor integrated circuit chip. The term is frequently used to refer to the central processing unit in a system. However, it can also refer to other co-processors.

There are all sorts of examples of different processors your computer will have: Central Processing Unit (CPU), Graphics Processing Unit (GPU), Digital Signal Processor (DSP), etc., but the main processor people think of when pondering computer processors is the one you might suspect: the central processing unit. As noted in the Wiki article, if designed conforming to the von Neumann architecture, the central processing unit contains at least a control unit, arithmetic logic unit, and processor registers.

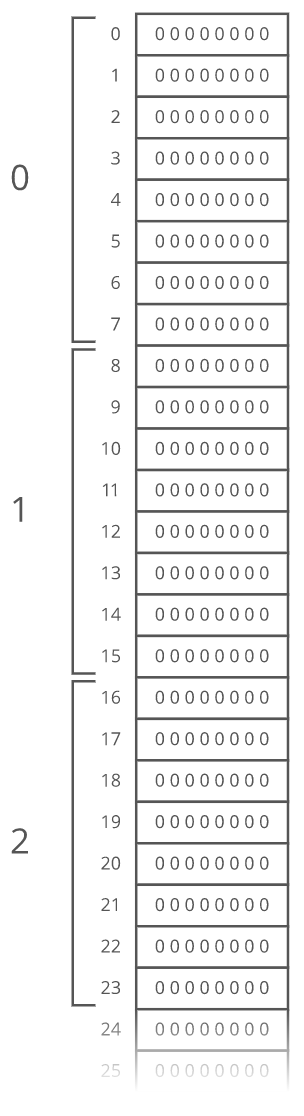

All this to say: our processor does all the real work inside our computer and it must be connected to our RAM bookshelf somehow:

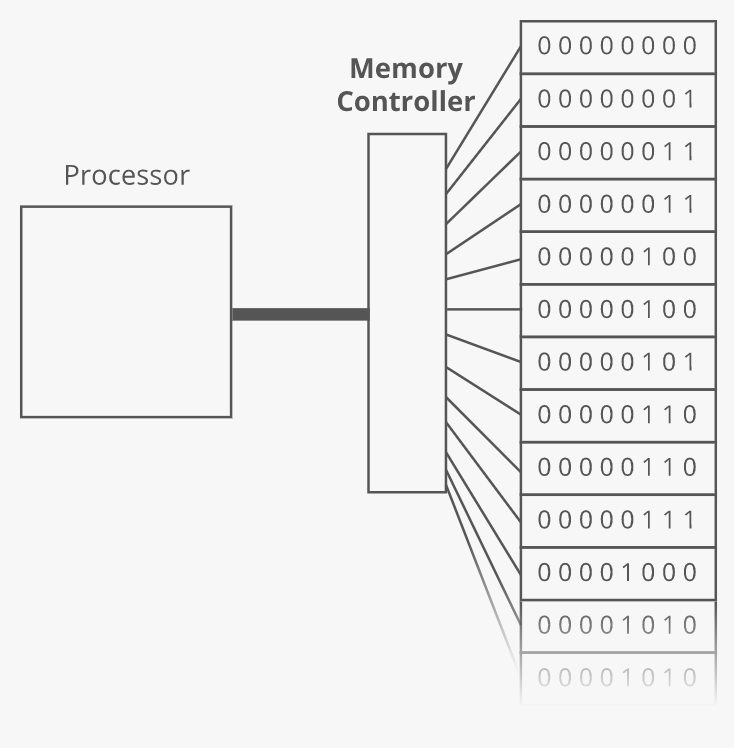

The connection between our computer's processor and the RAM bookshelf is made by means of a memory controller:

The memory controller does the actual reading and writing to and from RAM. It has a direct connection to each shelf of RAM. That direct connection turns out to be very important. It means we can access address 0 and then immediately access address 918873 without having to "climb down" our massive bookshelf of RAM.

That is why we call it Random Access Memory (RAM)--we can Access the bits at any Random address in Memory immediately.

Spinning hard drives don't have this "random access" superpower because there's no direct connection to each byte on the disk. Instead, there's a reader—-called a head—-that moves along the surface of a spinning storage disk (like the needle on a record player). Reading bytes that are far apart takes longer because you have to wait for the head to physically move along the disk.

Even though the memory controller can jump between far-apart memory addresses quickly, programs tend to access memory that's nearby. So computers are tuned to get an extra speed boost when reading memory addresses that are close to each other. The processor has a cache where it stores a copy of stuff that it has recently read from RAM. In truth, the processor actually has a series of caches (see the Wiki article on CPU cache for more about the different levels of chaching), but we can picture them all lumped together as one cache as follows:

This cache is much faster to read from than RAM, so the processor saves time whenever it can read something from cache instead of going out to RAM. When the processor asks for the contents of a given memory address, the memory controller also sends the contents of a handful of nearby memory addresses. And the processor puts all of it in the cache. So if the processor asks for the contents of address 951, then 952, then 953, then 954, and so on, then the processor will go out to RAM once for that first read, and the subsequent reads will come straight from the super-fast cache.

But if the processor asks to read address 951, then address 362, then address 419, and so on, then the cache won't help, and it'll have to go all the way out to RAM for each read. So reading from sequential memory addresses is faster than jumping around.

Understanding everything above is very important in the context of designing algorithms because that knowledge should directly influence what kinds of data structures you choose to implement and use for different programs. Knowing the strong and weak points of each data structure helps you to intentionally design programs with architectural optimization in mind instead of just blindly trying to get something to work.

Binary numbers

Let's put the bits we discussed in the RAM bookshelf analogy above to good use by storing some stuff. And let's start by storing numbers.

The number system we usually use is called base 10, because each digit has ten possible values (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 0). But computers don't have digits with ten possible values. They have bits with two possible values. So they use base 2 numbers. Base 10 is also called decimal. Base 2 is also called binary.

So far we've been talking about unsigned integers ("unsigned" means non-negative, and "integer" means a whole number, not a fraction or decimal). Storing other numbers isn't hard though. Here's how some other numbers could be stored:

- Fractions: Store two numbers: the numerator and the denominator.

- Decimals: Also two numbers:

- the number with the decimal point taken out, and

- the position where the decimal point goes (i.e., how many digits over from the leftmost digit).

- Negative numbers: Reserve the leftmost bit for expressing the sign of the number.

0for positive and1for negative.

In reality we usually do something slightly fancier for each of these. But these approaches work, and they show how we can express some complex stuff with just 1s and 0s.

NOTE (about negative numbers): The Wiki article on signed number representations is a good read. Specifically, the portion on two's complement is worth taking note of. The Wiki article on two's complement states the following: "Two's complement is the most common method of representing signed integers on computers." It may be worth noting how two's complement works. Without fussing over the details, here's the gist (more fun details about one's complement as well as two's complement may be found in Rosen's Discrete Math text on pages 180-181): "To represent an integer with for a specified positive integer , a total of bits is used. The leftmost bit is used to represent the sign. A 0 bit in this position is used for positive integers, and a 1 bit in this position is used for negative integers [...]." The point is that there are different ways of doing this (just like how to represent fractions, decimals, etc.).

We've talked about base 10 and base 2. You may have also seen base 16, also called hexadecimal or hex. In hex, our possible values for each digit are 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, a, b, c, d, e, and f. Hex numbers are often prefixed with 0x or #. In CSS, colors are sometimes expressed in hex. Interview Cake's signature blue color is #5bc0de.

Fixed-width integers

Question: How many different numbers can we express with 1 byte (i.e., 8 bits)?

Solution. The fundamental principle of counting tells us since there are 2 options for each bit (i.e., 1 or 0) and there are 8 bits whose values we must select, there will be a total of

different ways we can express a single byte with 8 bits. For example, the following are some such instances: 10101010, 10010001, 11000100, etc. These binary numbers are kind of hard to read as they are presented right now--bytes are often written by adding a single space between blocks of 4 bits so the previous byte examples would likely be written as follows in most places to enhance readability: 1010 1010, 1001 0001, 1100 0100, etc.

Question: What range (not how many) of signed base 10 integers can we express with 1 byte (i.e., 8 bits)?

Solution. This depends on how signed numbers are represented. Since two's complement is the most frequently used representation, we will use that as our model. As observed in the previous note, to represent an integer with for a specified positive integer , a total of bits is used. Hence, when 8 bits is used, we have and we can represent the integer with

Hence, in general, using two's complement to represent signed numbers (which most systems use), the range of signed base 10 integers that can be expressed is as follows:

signed base 10 integers using bits. Or

signed base 10 integers using bytes.

Integer overflow: What happens if we have the number 255 in an 8-bit unsigned integer (i.e., 1111 1111 in binary) and we add 1? The answer (i.e., 256) needs a 9th bit to handle this addition: 1 0000 0000. But we only have 8 bits! This situation is an example of integer overflow. At best, we might just get an error. At worst, our computer might compute the correct answer but then just throw out the 9th bit, giving us zero (i.e., 0000 0000) instead of 256 (i.e., 1 0000 0000)!

NOTE: Javascript automatically converts the result to Infinity if it gets too big.

The 256 possibilities we get with 1 byte are pretty limiting. So we usually use 4 or 8 bytes (32 or 64 bits) for storing integers. For example, look at the PostgreSQL data types documentation, specifically the entries for integer-related data types:

| Name | Aliases | Description | Range of integers that can be represented in base 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

smallint | int2 | signed two-byte integer | |

integer | int, int4 | signed four-byte integer | |

bigint | int8 | signed eight-byte integer |

Perhaps more meaningfully:

- 16-bit or two-byte integers have possible values--more than 65 thousand (exact: 65,536). Range of integers that can be represented in base 10 using two-byte integers:

- 32-bit or four-byte integers have possible values--more than 4 billion (exact: 4,294,967,296).

- 64-bit or eight-byte integers have possible values--more than 10 billion billion or (exact: 18,446,744,073,709,551,616).

You may say to yourself: "How come I've never had to think about how many bits my integers are?" Maybe you have but just didn't know it. Have you ever noticed how in some languages (like Java and C) sometimes numbers are IntegerS and sometimes they're LongS? The difference is the number of bits (in Java, IntegerS are 32 bits and LongS are 64 bits). Ever created a table in SQL? When you specify that a column will hold integers, you have to specify how many bytes: 1 byte (tinyint), 2 bytes (smallint), 4 bytes (int), or 8 bytes (bigint). When is 32 bits (i.e., 4 bytes), the most commonly used way to store integers not enough? When you're counting views on a viral video. YouTube famously ran into trouble when the Gangnam Style video hit over views, forcing them to upgrade their view counts from 32-bit to 64-bit signed integers.

NOTE (maximum safe integer in JavaScript): JavaScript is different than SQL and every programming language has its quirks. For JavaScript, the Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER constant represents the maximum safe integer in JavaScript: : 9,007,199,254,740,991 or simply 9007199254740991. As MDN notes in the above link, the reasoning behind the number is that JavaScript uses double-precision floating format numbers as specified in IEEE 754 and can only safely represent integers between and . If you need to use a number outside of this range, then use JavaScript's BigInt.

Most integers are fixed-width or fixed-length, which means the number of bits they take up doesn't change. It's usually safe to assume an integer is fixed-width unless you're told otherwise. Variable-size numbers exist, but they're only used in special cases. If we have a 64-bit fixed-length integer, it doesn't matter if that integer is 0 or 193,457—-it still takes up the same amount of space in RAM: 64 bits.

In big O notation, we say fixed-width integers take up constant space or space. And because they have a constant number of bits, most simple operations on fixed-width integers (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division) take constant time (i.e., time). So fixed-width integers are very space efficient and time efficient. But that efficiency comes at a cost—-their values are limited. Specifically, they're limited to possibilities, where is the number of bits.

So there's a tradeoff. As we'll see, that's a trend in data structures-—to get a nice property, we'll often have to lose something.

Arrays

From the above discussion of RAM, binary numbers, and fixed-width numbers, we know how to store individual numbers. Let's now talk about storing several numbers.

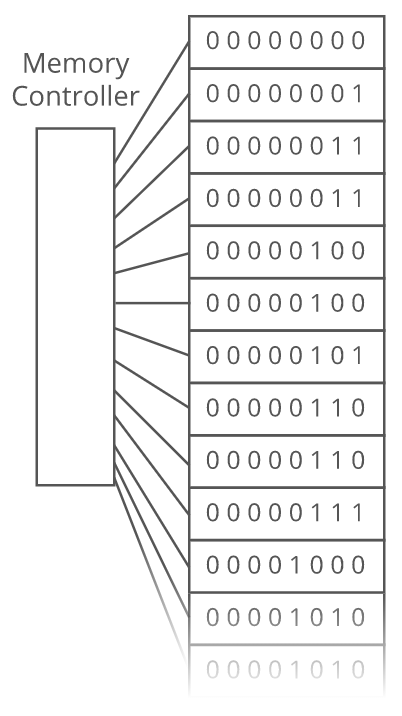

Suppose we wanted to keep a count of how many bottles of kombucha we drink every day. Let's store each day's kombucha count in an 8-bit, fixed-width, unsigned integer. That should be plenty—-we're not likely to get through more than 256 (i.e., ) bottles in a single day, right? Let's store the kombucha counts right next to each other in RAM, starting at memory address 0:

From the figure above, it looks like our kombucha count for the first day is 3 (i.e., since , then 1 for the second day, 5 for the third day, 4 for the fourth day, 3 for the fifth day, and so on.

This is an array. RAM is basically an array already. Just like with RAM, the elements of an array are numbered. We call that number the index of the array element (plural: indices). In this example, each array element's index is the same as its address in RAM. But that's not usually true. Suppose another program like Spotify had already stored some information at memory address 2:

We'd have to start our array below it, for example at memory address 3. So index 0 in our array would be at memory address 3, and index 1 would be at memory address 4, etc.:

Suppose we wanted to get the kombucha count at index 4 in our array. How do we figure out what address in memory to go to? Simple math: Take the array's starting address (which is 3 in this case), add the index we're looking for (which is 4 in this case), and that's the address of the item we're looking for: . In general, for getting the th item in our array:

This works out nicely because the size of the addressed memory slots and the size of each kombucha count are both 1 byte. So a slot in our array corresponds to a slot in RAM. But that's not always the case. In fact, it's usually not the case. We usually use 64-bit integers. So how do we build an array of 64-bit (8 byte) integers on top of our 8-bit (1 byte) memory slots? We simply give each array index 8 address slots instead of 1:

So we can still use simple math to grab the start of the th item in our array—-we just have to throw in some multiplication:

Adding this multiplication step doesn't really slow us down. Remember: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division of fixed-width integers takes time. So all the math we're using here to get the address of the th item in the array takes time. And remember how we said the memory controller has a direct connection to each slot in RAM? That means we can read the stuff at any given memory address in time.

Together, this means looking up the contents of a given array index is time. This fast lookup capability is the most important property of arrays. But the formula we used to get the address of the th item in our array only works if the following conditions are met:

- Elements are the same size: Each item in the array is the same size (i.e., takes up the same number of bytes whether that's 1 or 8).

- Elements are continguous in memory: The array must be uninterrupted or contiguous in memory. There cannot be any gaps in the array...like to "skip over" a memory slot Spotify was already using.

These conditions make our formula for finding the th item work because they make our array predictable. We can predict exactly where in memory the th element of our array will be. But they also constrain what kinds of things we can put in an array. Every item has to be the same size. And if our array is going to store a lot of stuff, we'll need a bunch of uninterrupted free space in RAM. Which gets hard when most of our RAM is already occupied by other programs (like Spotify). That's the tradeoff. Arrays have fast lookups ( time), but each item in the array needs to be the same size, and you need a big block of uninterrupted free memory to store the array.

Strings

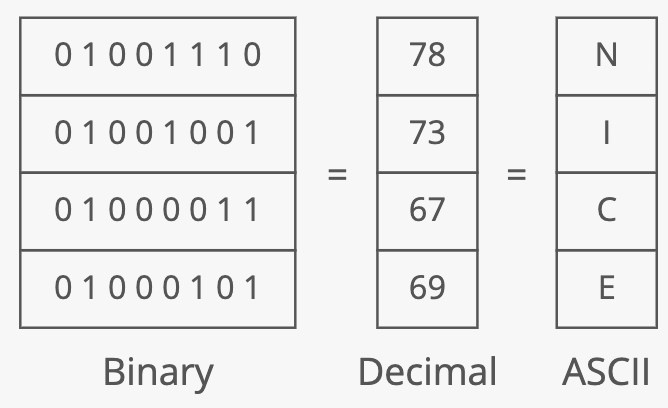

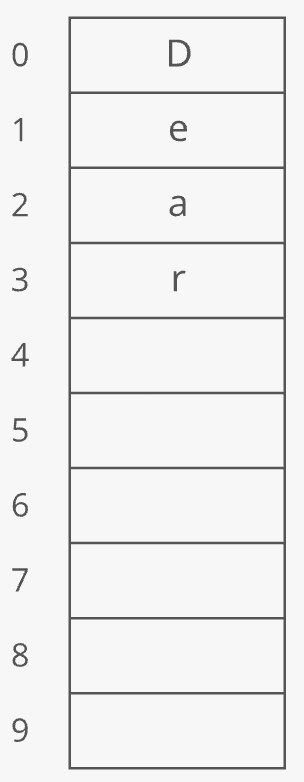

Instead of storing numbers, let's now store some words. A series of characters (letters, punctuation, etc.) is called a string.

We already know one way to store a series of things: arrays. But how can an array store characters instead of numbers? This shouldn't be too hard. Let's define a mapping between numbers (which we already know how to store) and characters (which we can then store using our mapping). Let's say "A" is 1 (or 0000 0001 in binary), "B" is 2 (or 0000 0010 in binary), etc. Now we have characters. The mapping of numbers to characters is called a character encoding. One common character encoding is ASCII. Here's how the alphabet is encoded in ASCII:

The idea is clear. Since we can express characters as 8-bit integers, we can express strings as arrays of 8-bit numbers characters.

It's probably worth noting that UTF-8 is one of the most frequently used character encodings (it's backwards compatible with ASCII and far more robust).

Pointers

In the note on arrays, we said every item in an array had to be the same size (for our lookup formula to work). Let's dig into this point a little more.

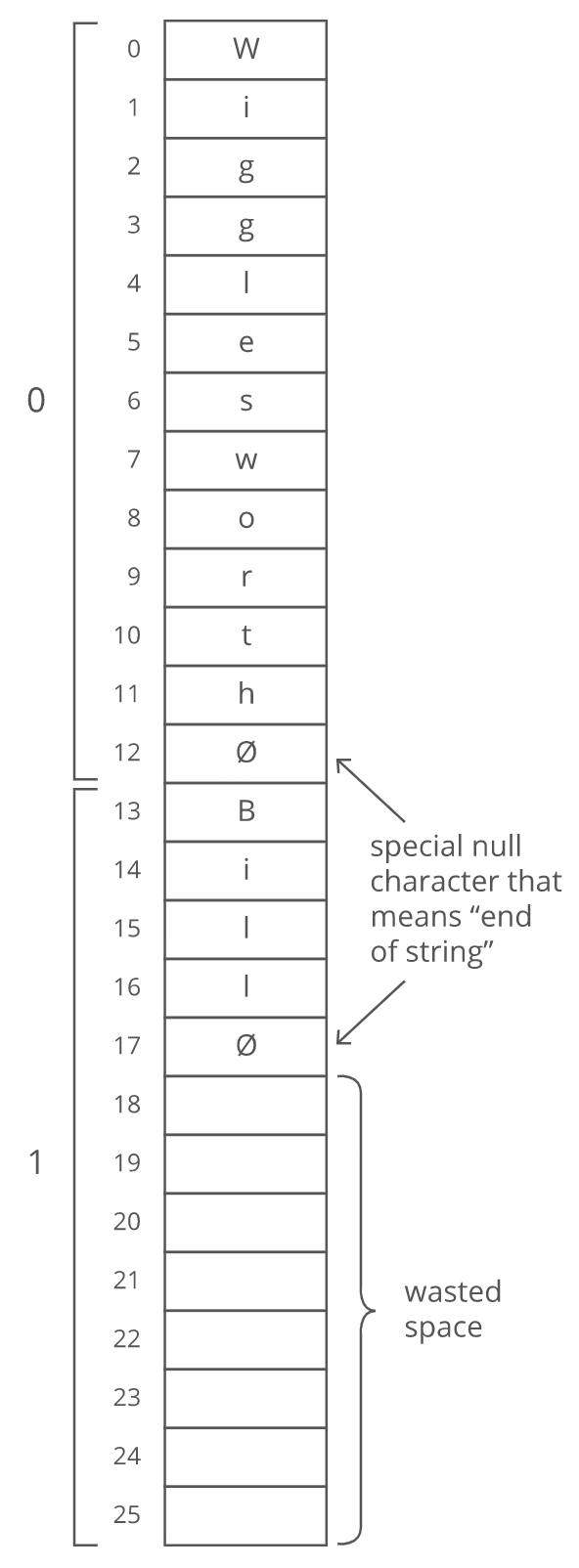

Suppose we wanted to store a bunch of ideas for baby names. Because we've got some really cute ones. Each name is a string. Which is really an array. And now we want to store those arrays in an array. Whoa. Now, what if our baby names have different lengths? That'd violate our rule that all the items in an array need to be the same size! We could put our baby names in arbitrarily large arrays (say, 13 characters each), and just use a special character to mark the end of the string within each array:

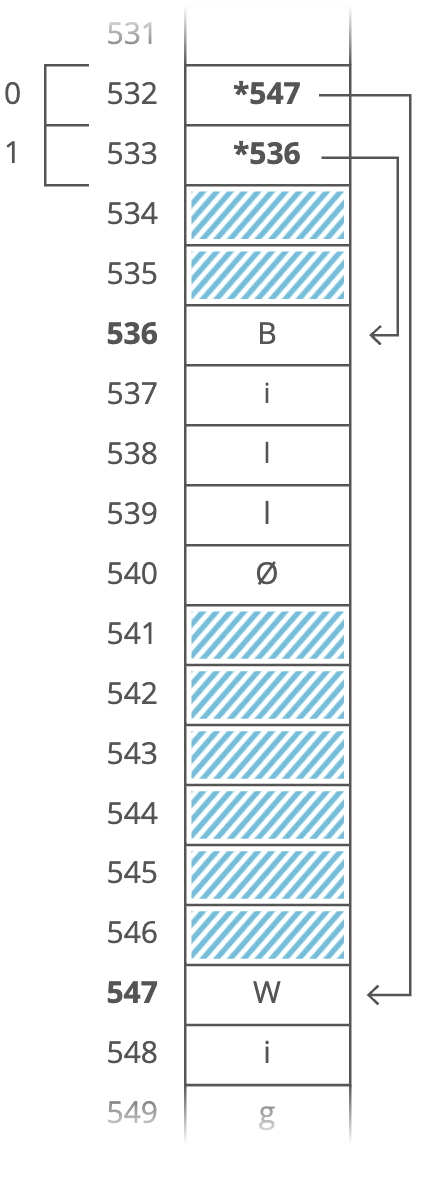

But look at all that wasted space after "Bill". And what if we wanted to store a string that was more than 13 characters? We'd be out of luck. There's a better way. Instead of storing the strings right inside our array, let's just put the strings wherever we can fit them in memory. Then we'll have each element in our array hold the address in memory of its corresponding string. Each address is an integer, so really our outer array is just an array of integers. We can call each of these integers a pointer, since it points to another spot in memory.

In the figure above, the pointers are marked with a * at the beginning (i.e., *547 is a pointer as well as *536).

This seems to be pretty clever. After all, it appears to fix both of the disadvantages/requirements of arrays that we previously highlighted:

- Elements must be the same size: The items do not have to be the same size or length anymore--each string can be as long or as short as we want.

- Elements must be continguous in memory: We don't need enough uninterrupted free memory to store all our strings next to each other—we can place each of them separately, wherever there's space in RAM.

We fixed it! No more tradeoffs. Right? Nope. Now we have a new tradeoff: Remember how the memory controller sends the contents of nearby memory addresses to the processor with each read? And the processor caches them? So reading sequential addresses in RAM is faster because we can get most of those reads right from the cache?

Our original array was very cache-friendly, because everything was sequential. So reading from the 0th index, then the 1st index, then the 2nd, etc., got an extra speedup from the processor cache. But the pointers in this array make it not cache-friendly because the baby names are scattered randomly around RAM. So reading from the 0th index, then the 1st index, etc., doesn't get that extra speedup from the cache. That's the tradeoff. This pointer-based array requires less uninterrupted memory and can accommodate elements that aren't all the same size, but it's slower because it's not cache-friendly. This slowdown isn't reflected in the big O time cost. Lookups in this pointer-based array are still time--we just don't benefit from the processor caching that we might benefit from otherwise.

Dynamic arrays

Let's try to go about how we might build a very simple word processor.

What data structure should we use to store the text as our user writes it? Strings are stored as arrays, right? So we should use an array? Here's where that gets tricky: when we allocate an array in a low-level language like C or Java, we have to specify upfront how many indices we want our array to have. There's a reason for this—-the computer has to reserve space in memory for the array and commit to not letting anything else use that space. We can't have some other program overwriting the elements in our array! The computer can't reserve all its memory for a single array. So we have to tell it how much to reserve. But for our word processor, we don't know ahead of time how long the user's document is going to be! So what can we do?

To skirt this issue, we can make an array and program it to resize itself when it runs out of space! This is called a dynamic array, and it's built on top of a normal array.

NOTE: Python, Ruby, and JavaScript use dynamic arrays for their default array-like data structures. In Javascript, they're called "arrays." Other languages have both. For example, in Java, array is a static array (whose size we have to define ahead of time) and ArrayList is a dynamic array.

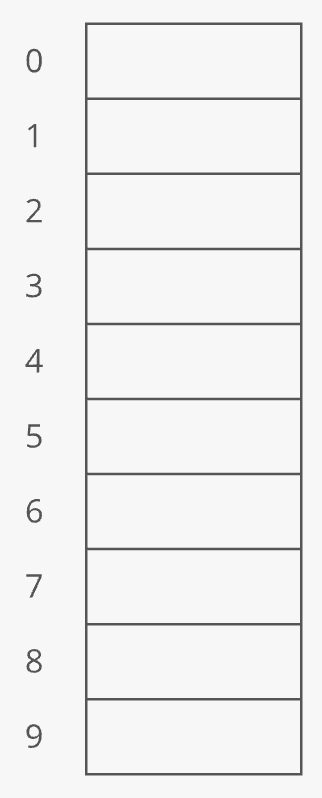

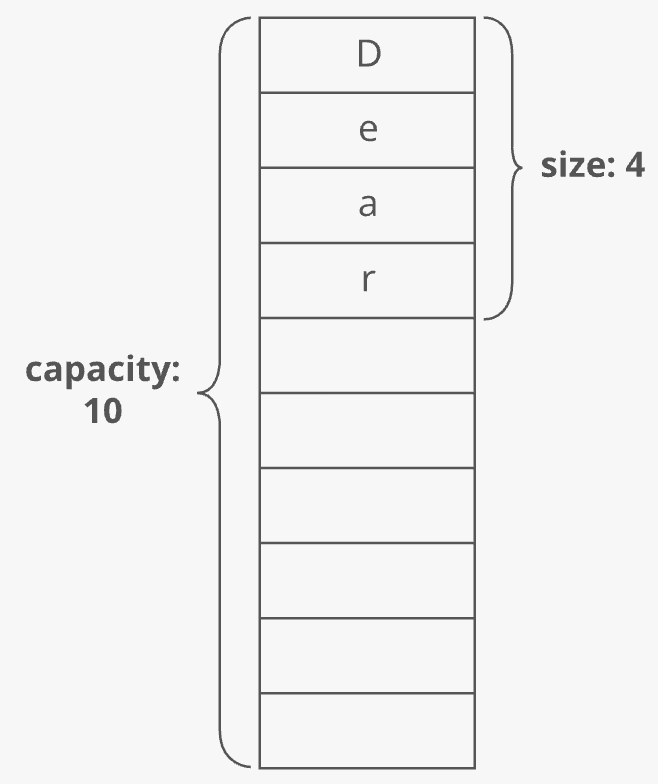

Here's how it works: When you allocate a dynamic array, your dynamic array implementation makes an underlying static array. The starting size depends on the implementation-—let's say our implementation uses 10 indices:

Suppose you append 4 items to this dynamic array:

At this point, our dynamic array contains 4 items. It has a length of 4. But the underlying array has a length of 10. We'd say this dynamic array's size is 4 and its capacity is 10:

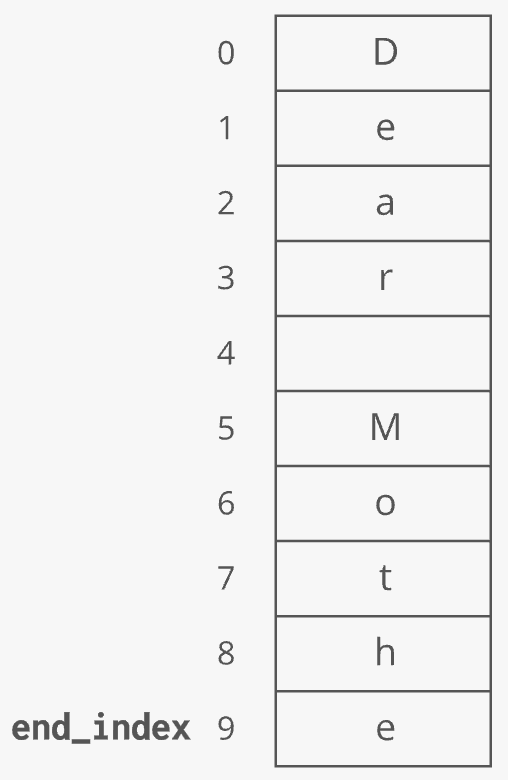

The dynamic array stores an end_index variable to keep track of where the dynamic array ends and the extra capacity begins:

If you keep appending, at some point you'll use up the full capacity of the underlying array:

Next time you append, the dynamic array implementation will typically execute a few steps under the hood to make this work:

- Make a new, bigger array

- Copy each element from the old array into the new array

- Free up the old array

- Append your new item

Let's try to visualize these steps using the illustration above:

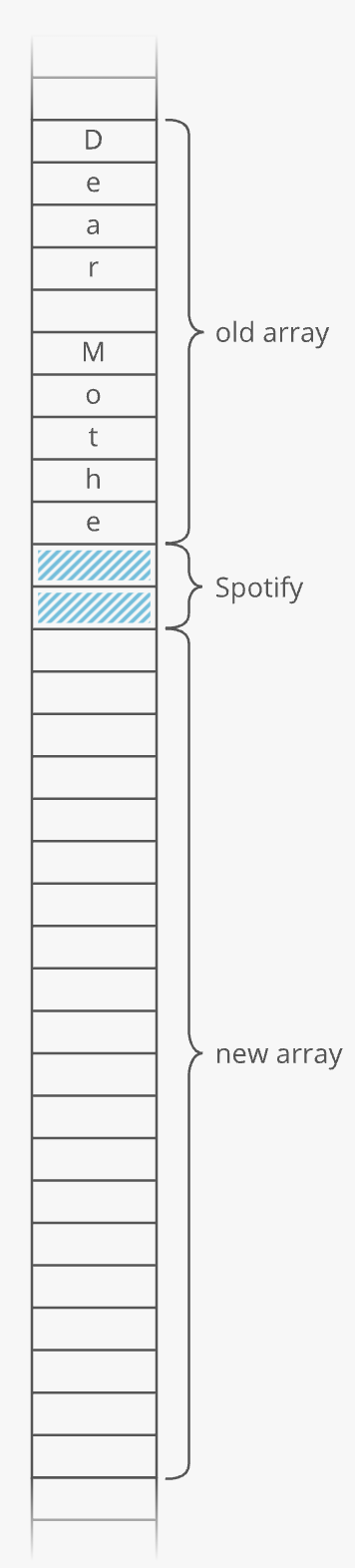

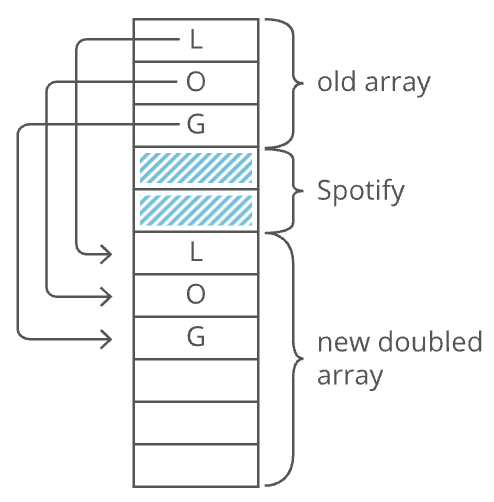

1. Make a new, bigger array

Usually twice as big.

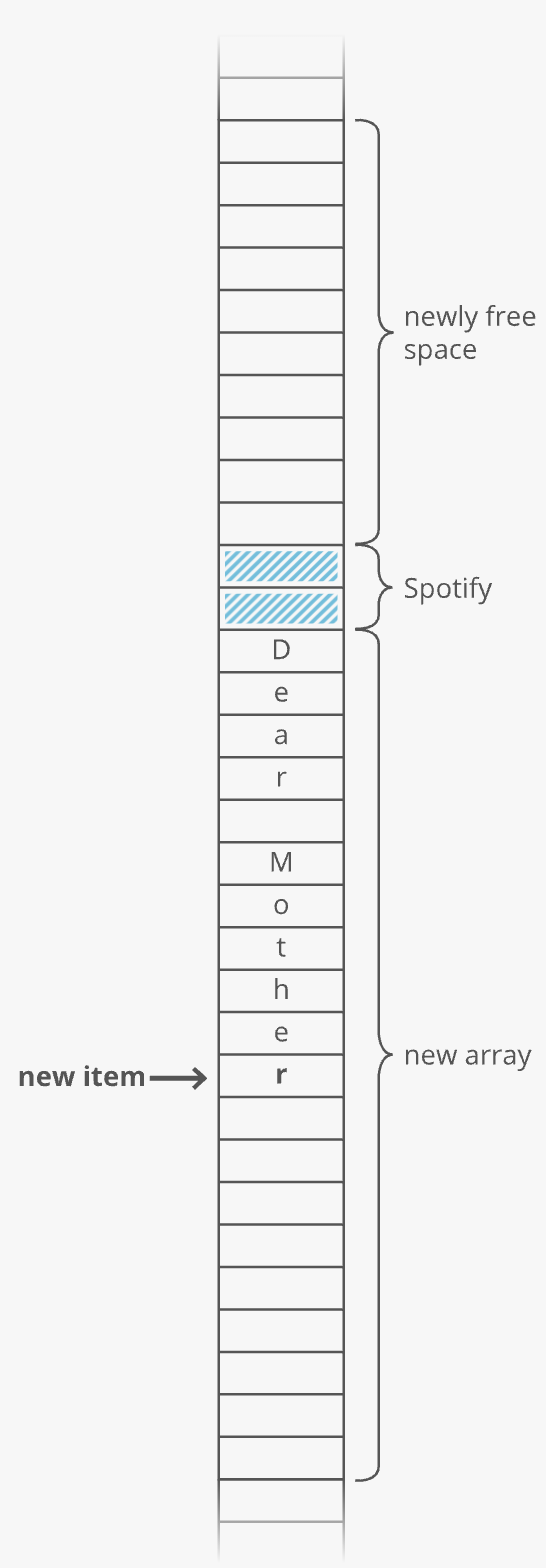

Why not just extend the existing array? Because that memory might already be taken. Say we have Spotify open and it's using a handful of memory addresses right after the end of our old array. We'll have to skip that memory and reserve the next 20 uninterrupted memory slots for our new array:

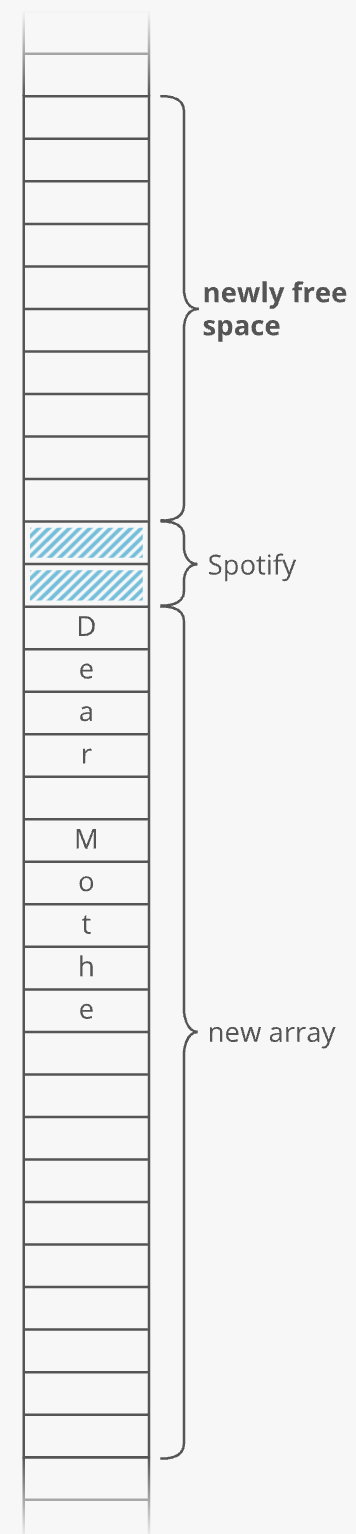

2. Copy each element from the old array into the new array

3. Free up the old array

This tells the operating system, "you can use this memory for something else now."

4. Append your new item

The upshot of all this

We could call the special appends described above as "doubling" appends since they require us to make a new array that's (usually) double the size of the old one. Appending an item to an array is usually an time operation, but a single doubling append is an time operation since we have to copy all items from our array.

Does that mean an append operation on a dynamic array is always worst-case time? Yes. So if we make an empty dynamic array and append times, then does this mean that such appending has some crazy time cost like or ? Not quite.

While the time cost of each special double append doubles each time, the number of appends you get until the next doubling append also doubles. This more or less "cancels out", and we can effectively say each append has an average cost or amortized cost of :

Amortized cost

Amortize is a fancy verb used in finance that refers to paying off the cost of something gradually. With dynamic arrays, every expensive append where we have to grow the array "buys" us many cheap appends in the future. Conceptually, we can spread the cost of the expensive append over all those cheap appends.

Instead of looking at the worst case for an append individually, let's look at the overall cost of doing many appends—-let's say appends. The cost of doing appends has two parts:

- The cost of actually appending all items.

- The cost of any "doubling" we need to do along the way.

The first part is easy—-each of our items costs time to append. So that's time for all of them.

The second part is trickier. How much do all the doubling operations cost? Remember: with each "doubling" we double the capacity of our underlying array. So it'll be twice as long until the next doubling as it was until the previous doubling. Say we start off with space for just one item. Our first doubling will involve copying over just one item. We'll need to double again with two items. That'll involve copying over two items. And we'll need to double again with four items. And again with eight items. And so on.

So, the total cost for copying over items across all of our doubling operations is:

It's helpful to look at this sum from right to left:

We can see what this comes to when we draw it out. If this is :

is half the size:

is half the size of that:

And so on:

We can see that the whole right side ends up being another square of size , making the sum . So when we do appends, the appends themselves cost , and the doubling costs . Put together, we've got a cost of , which is . So on average, each individual append is . appends cost us .

Remember: even though the amortized cost of an append is , the worst case cost is still . Some appends will take a long time.

In industry we usually wave our hands and say dynamic arrays have a time cost of for appends even though strictly speaking that's only true for the average case or the amortized cost. In an interview, if we were worried about that -time worst-case cost of appends, we might try to use a normal, non-dynamic array.

The advantage of dynamic arrays over arrays is that you don't have to specify the size ahead of time, but the disadvantage is that some appends can be expensive. That's the tradeoff.

But what if we wanted the best of both worlds...

Linked Lists

Our word processor is definitely going to need fast appends-—appending to the document is basically the main thing you do with a word processor. Can we build a data structure that can store a string, has fast appends, and doesn't require you to say how long the string will be ahead of time?

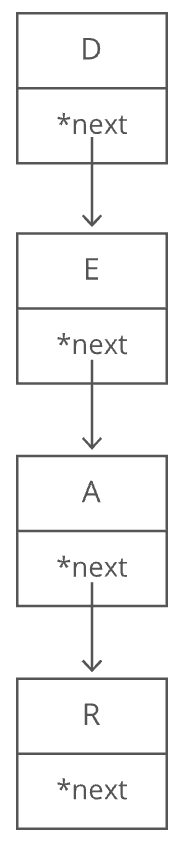

Let's focus first on not having to know the length of our string ahead of time. Remember how we used pointers to get around length issues with our array of baby names? What if we pushed that idea even further? What if each character in our string were a two-index array with:

- the character itself

- a pointer to the next character

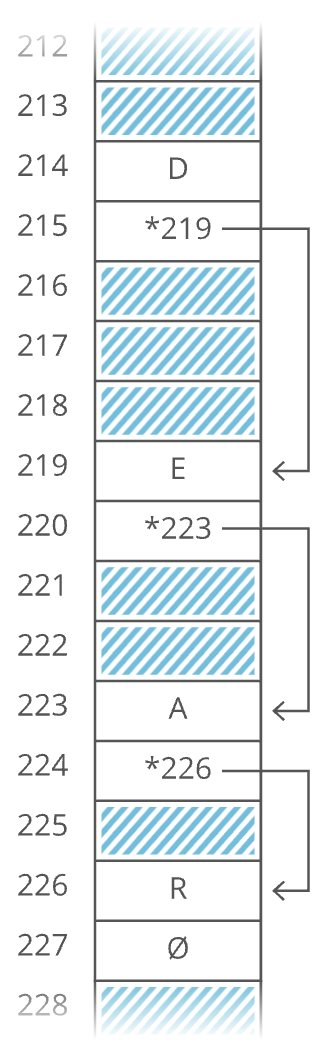

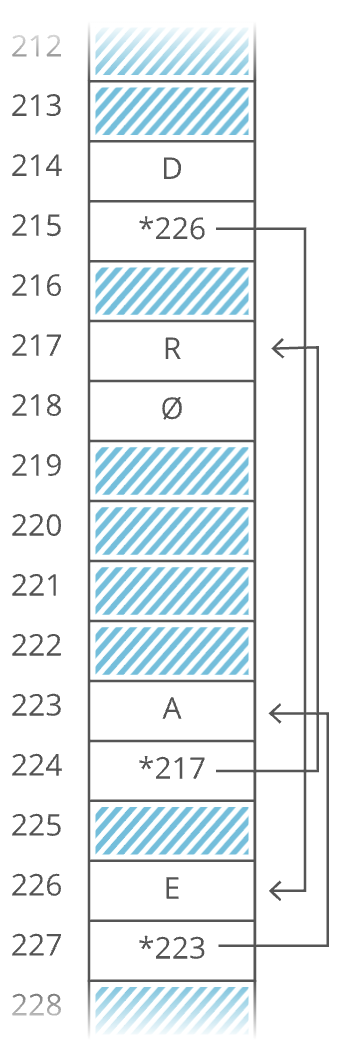

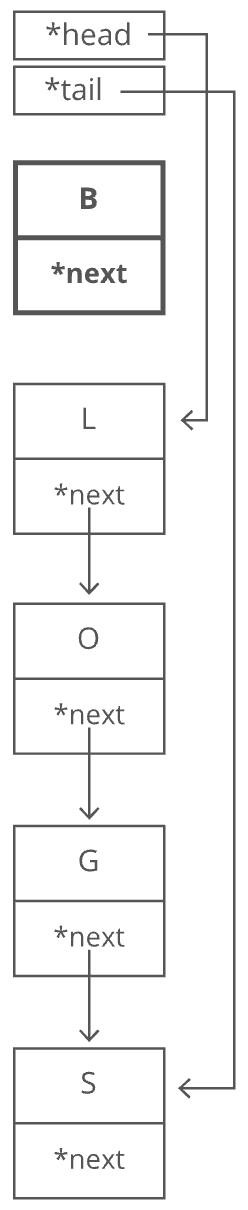

We would call each of these two-item arrays a node and we'd call this series of nodes a linked list. Here's how we'd actually implement it in memory:

Notice how we're free to store our nodes wherever we can find two open slots in memory. They don't have to be next to each other. They don't even have to be in order:

"But that's not cache-friendly," you may be thinking. Good point! We'll get to that.

The first node of a linked list is called the head, and the last node is usually called the tail.

Note: Confusingly, some people prefer to use "tail" to refer to everything after the head of a linked list. In an interview it's fine to use either definition. Briefly say which definition you're using, just to be clear.

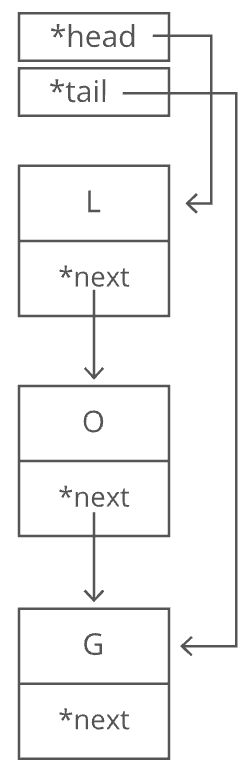

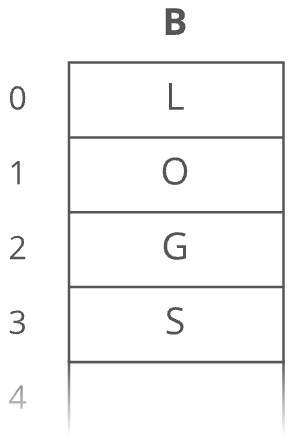

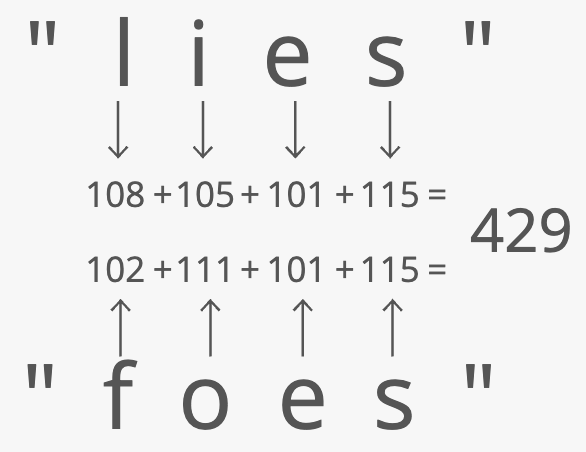

It's important to have a pointer variable referencing the head of the list; otherwise, we'd be unable to find our way back to the start of the list! We'll also sometimes keep a pointer to the tail. That comes in handy when we want to add something new to the end of the linked list. In fact, let's try that out. Suppose we had the string "LOG" stored in a linked list:

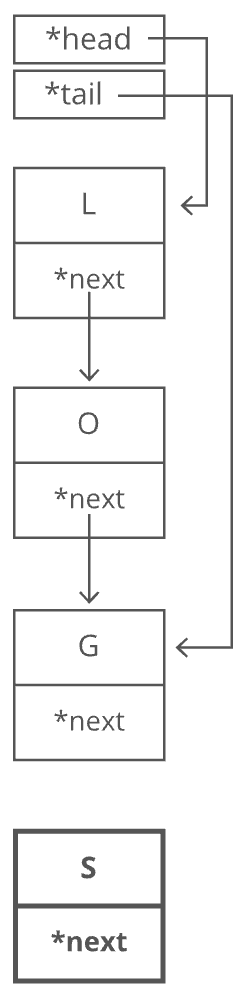

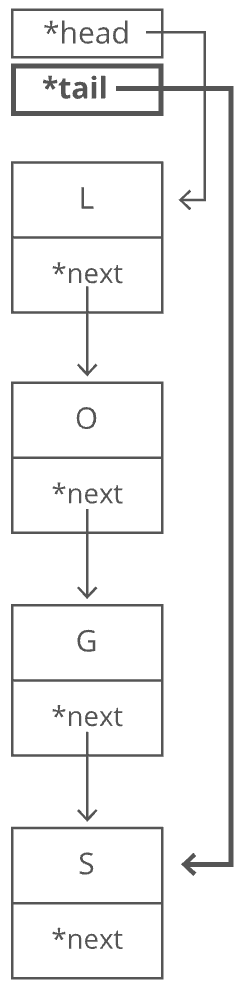

Suppose we wanted to add an "S" to the end, to make it "LOGS". How would we do that? Easy. We just put it in a new node:

And of course we'd have to tweak some pointers.

- Grab the last letter, which is "G". Our

tailpointer lets us do this in time.

- Point the last letter's

nextpointer to the letter we're appending ("S").

- Update the

tailpointer to point to our new last letter, "S".

That's time. Why? Because the runtime doesn't get bigger if the string gets bigger. No matter how many characters are in our string, we still just have to tweak a couple pointers for any append.

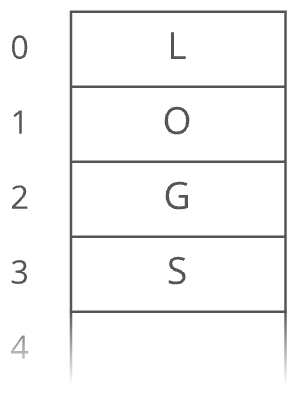

Now, what if instead of a linked list, our string had been a dynamic array? We might not have any room at the end, forcing us to do one of those doubling operations to make space:

So with a dynamic array, our append would have a worst-case time cost of . Linked lists have worst-case -time appends, which is better than the worst-case time of dynamic arrays. That worst-case part is important. The average case runtime for appends to linked lists and dynamic arrays is the same: .

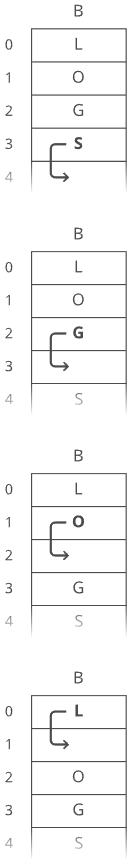

Now, what if we wanted to prepend something to our string? Let's say we wanted to put a "B" at the beginning. For our linked list, it's just as easy as appending. Create the node:

And then tweak some pointers:

- Point "B"'s

nextto "L". - Point the

headto "B".

This is time again.

But if our string were a dynamic array ...

And we wanted to add in that "B":

We have to make room for the "B". We have to move each character one space down:

Now we can drop the "B" in there:

What is our time cost here? It's all in the step where we made room for the first letter. We had to move all characters in our string. One at a time. That's time.

So linked lists have faster prepends than dynamic arrays (i.e., time for linked lists instead of time for dynamic arrays). There's no "worst case" caveat this time-—prepends for dynamic arrays are always time. And prepends for linked lists are always time. These quick appends and prepends for linked lists come from the fact that linked list nodes can go anywhere in memory. They don't have to sit right next to each other the way items in an array do.

If linked lists are so great, then why do we usually store strings in an array? Because arrays have -time lookups. And those constant-time lookups come from the fact that all the array elements are lined up next to each other in memory.

Lookups with a linked list are more of a process, because we have no way of knowing where the th node is in memory. So we have to walk through the linked list node by node, counting as we go, until we hit the th item.

function getIthItemInLinkedList(head, i) {

if (i < 0) {

throw new Error("i can't be negative: " + i);

}

let currentPosition = 0;

let currentNode = head;

while (currentNode) {

if (currentPosition === i) {

// found it!

return currentNode;

}

// move on to the next node

currentNode = currentNode.next;

currentPosition++;

}

throw new Error("List has fewer than i + 1 (" + (i + 1) + ") nodes");

}

That's steps down our linked list to get to the th node (we made our function zero-based to match indices in arrays). So linked lists have -time lookups. Much slower than the -time lookups for arrays and dynamic arrays. Not only that—-walking down a linked list is not cache-friendly. Because the next node could be anywhere in memory, we don't get any benefit from the processor cache. This means lookups in a linked list are even slower. So the tradeoff with linked lists is they have faster prepends and faster appends than dynamic arrays, but they have slower lookups.

Hash tables

Quick lookups are often really important. For that reason, we tend to use arrays (which have -time lookups) much more often than linked lists (which have -time lookups).

For example, suppose we wanted to count how many times each ASCII character appears in Romeo and Juliet. How would we store those counts? We can use arrays in a clever way here. Remember—-characters are just numbers. In ASCII (a common character encoding) 'A' is 65, 'B' is 66, etc. So we can use the character('s number value) as the index in our array, and store the count for that character at that index in the array:

With this array, we can look up (and edit) the count for any character in constant time. Because we can access any index in our array in constant time. Something interesting is happening here-—this array isn't just a list of values. This array is storing two things: characters and counts. The characters are implied by the indices. So we can think of an array as a table with two columns except you don't really get to pick the values in one column (the indices)-—they're always 0, 1, 2, 3, etc.

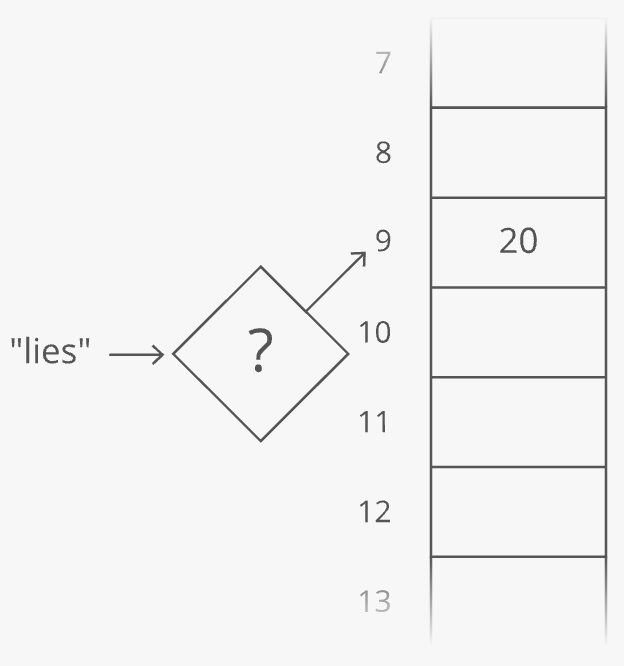

But what if we wanted to put any value in that column and still get quick lookups? Suppose we wanted to count the number of times each word appears in Romeo and Juliet. Can we adapt our array? Translating a character into an array index was easy. But we'll have to do something more clever to translate a word (a string) into an array index ...

Here's one way we could do it: Grab the number value for each character and add those up.

The result is 429. But what if we only have 30 slots in our array? We'll use a common trick for forcing a number into a specific range: the modulus operator (%). Modding our sum by 30 ensures we get a whole number that's less than 30 (and at least 0):

Bam. That'll get us from a word (or any string) to an array index.

This data structure is called a hash table or hash map. In our hash table, the counts are the values and the words ("lies," etc.) are the keys (analogous to the indices in an array). The process we used to translate a key into an array index is called a hashing function.

The hashing functions used in modern systems get pretty complicated-—the one we used here is a simplified example. Note that our quick lookups are only in one direction-—we can quickly get the value for a given key, but the only way to get the key for a given value is to walk through all the values and keys. Same thing with arrays—-we can quickly look up the value at a given index, but the only way to figure out the index for a given value is to walk through the whole array.

One problem—-what if two keys hash to the same index in our array? Look at "lies" and "foes":

They both sum up to 429! So of course they'll have the same answer when we mod by 30:

So our hashing function gives us the same answer for "lies" and "foes." This is called a hash collision. There are a few different strategies for dealing with them.

Here's a common one: instead of storing the actual values in our array, let's have each array slot hold a pointer to a linked list holding the counts for all the words that hash to that index:

One problem-—how do we know which count is for "lies" and which is for "foes"? To fix this, we'll store the word as well as the count in each linked list node:

"But wait!" you may be thinking, "Now lookups in our hash table take time in the worst case, since we have to walk down a linked list." That's true! You could even say that in the worst case every key creates a hash collision, so our whole hash table degrades to a linked list.

In industry though, we usually wave our hands and say collisions are rare enough that on average lookups in a hash table are time. And there are fancy algorithms that keep the number of collisions low and keep the lengths of our linked lists nice and short. But that's sort of the tradeoff with hash tables. You get fast lookups by key, except some lookups could be slow. And of course, you only get those fast lookups in one direction--looking up the key for a given value still takes time.

Summary

Arrays have -time lookups. But you need enough uninterrupted space in RAM to store the whole array. And the array items need to be the same size.

But if your array stores pointers to the actual array items (like we did with our list of baby names), you can get around both those weaknesses. You can store each array item wherever there's space in RAM, and the array items can be different sizes. The tradeoff is that now your array is slower because it's not cache-friendly.

Another problem with arrays is you have to specify their sizes ahead of time. There are two ways to get around this: dynamic arrays and linked lists. Linked lists have faster appends and prepends than dynamic arrays, but dynamic arrays have faster lookups.

Fast lookups are really useful, especially if you can look things up not just by indices (0, 1, 2, 3, etc.) but by arbitrary keys ("lies", "foes"...any string). That's what hash tables are for. The only problem with hash tables is they have to deal with hash collisions, which means some lookups could be a bit slow.

Each data structure has tradeoffs. You can't have it all.

So you have to know what's important in the problem you're working on. What does your data structure need to do quickly? Is it lookups by index? Is it appends or prepends?

Once you know what's important, you can pick the data structure that does it best.

Logarithms

What "logarithm" means

Here's what a logarithm is asking: "What power must we raise this base to in order to get this answer?"

Hence, for an expression like

the number 10 is called the base, and we can think of 100 here as the "answer". It's what we're taking the logarithm of. All it means is, "What power do we need to raise this base (i.e., 10) to in order to get this answer (i.e., 100)?"

What value of gets us our result of 100? The answer, of course, is 2: . So we can say .

What logarithms are used for

The main thing we use logarithms for is solving for when is in an exponent. So if we need to solve , then we need to bring the down from the exponent somehow. And logarithms give us a trick for doing that. We take of both sides: . This simplifies to which further simplifies to .

Logarithm rules

The following logarithmic rules are helpful if you're trying to do some algebraic stuff with logs:

| Rule Description | Rule in Algebraic Terms |

|---|---|

| Simplification | |

| Multiplication | |

| Division | |

| Powers | |

| Change of base |

Where logs come up in algorithms and interviews

"How many times must we double 1 before we get to " is a question we often ask ourselves in computer science. Or, equivalently, "How many times must we divide in half in order to get back down to 1?"

Can you see how those are the same question? We're just going in different directions! From to 1 by dividing by 2, or from 1 to by multiplying by 2. Either way, it's the same number of times that we have to do it.

The answer to both of these questions is or using the modern notation where stands for a logarithm of base 2 which is often written as .

It's okay if it's not obvious yet why that's true. We'll derive it with some examples.

Example 1: Logarithms in binary search

This comes up in the time cost of binary search, which is an algorithm for finding a target number in a sorted array. The process goes like this:

- Start with the middle number: is it bigger or smaller than our target number? Since the array is sorted, this tells us if the target would be in the left half or the right half of our array.

- We've effectively divided the problem in half. We can "rule out" the whole half of the array that we know doesn't contain the target number.

- Repeat the same approach (of starting in the middle) on the new half-size problem. Then do it again and again, until we either find the number or "rule out" the whole set.

In code:

function binarySearch(target, nums) {

// See if target appears in nums

// We think of floorIndex and ceilingIndex as "walls" around

// the possible positions of our target so by -1 below we mean

// to start our wall "to the left" of the 0th index

// (we *don't* mean "the last index")

let floorIndex = -1;

let ceilingIndex = nums.length;

// If there isn't at least 1 index between floor and ceiling,

// we've run out of guesses and the number must not be present

while (floorIndex + 1 < ceilingIndex) {

// Find the index ~halfway between the floor and ceiling

// We have to round down to avoid getting a "half index"

const distance = ceilingIndex - floorIndex;

const halfDistance = Math.floor(distance / 2);

const guessIndex = floorIndex + halfDistance;

const guessValue = nums[guessIndex];

if (guessValue === target) {

return true;

}

if (guessValue > target) {

// Target is to the left, so move ceiling to the left

ceilingIndex = guessIndex;

} else {

// Target is to the right, so move floor to the right

floorIndex = guessIndex;

}

}

return false;

}

So what's the time cost of binary search? The only non-constant part of our time cost is the number of times our while loop runs. Each step of our while loop cuts the range (dictated by floorIndex and ceilingIndex) in half, until our range has just one element left.

So the question is, "how many times must we divide our original array size () in half until we get down to 1?"

How many 's are there? We don't know yet, but we can call that number :

The above simplifies to , but we need to solve for . And the way we do this is with logarithms: . So there it is. The total time cost of binary search is .

Example 2: Logarithms in sorting

Sorting, in general, costs time. More specifically, is the best worst-case runtime we can get for sorting.

That's our best runtime for comparison-based sorting. If we can tightly bound the range of possible numbers in our array, we can use a hash map to do it in time with counting sort.

The easiest way to see why is to look at merge sort. In merge sort, the idea is to divide the array in half, sort the two halves, and then merge the two sorted halves into one sorted whole. But how do we sort the two halves? Well, we divide them in half, sort them, and merge the sorted halves. And so on.

function mergeSort(arrayToSort) {

// BASE CASE: arrays with fewer than 2 elements are sorted

if (arrayToSort.length < 2) {

return arrayToSort;

}

// STEP 1: divide the array in half

// We need to round down to avoid getting a "half index"

const midIndex = Math.floor(arrayToSort.length / 2);

const left = arrayToSort.slice(0, midIndex);

const right = arrayToSort.slice(midIndex);

// STEP 2: sort each half

const sortedLeft = mergeSort(left);

const sortedRight = mergeSort(right);

// STEP 3: merge the sorted halves

const sortedArray = [];

let currentLeftIndex = 0;

let currentRightIndex = 0;

while (sortedArray.length < left.length + right.length) {

// sortedLeft's first element comes next

// if it's less than sortedRight's first

// element or if sortedRight is exhausted

if (currentLeftIndex < left.length &&

(currentRightIndex === right.length ||

sortedLeft[currentLeftIndex] < sortedRight[currentRightIndex])) {

sortedArray.push(sortedLeft[currentLeftIndex]);

currentLeftIndex += 1;

} else {

sortedArray.push(sortedRight[currentRightIndex]);

currentRightIndex += 1;

}

}

return sortedArray;

}

So what's our total time cost? . The comes from the number of times we have to cut in half to get down to subarrays of just 1 element (our base case). The additional comes from the time cost of merging all items together each time we merge two sorted subarrays.

Example 3: Logarithms in binary trees

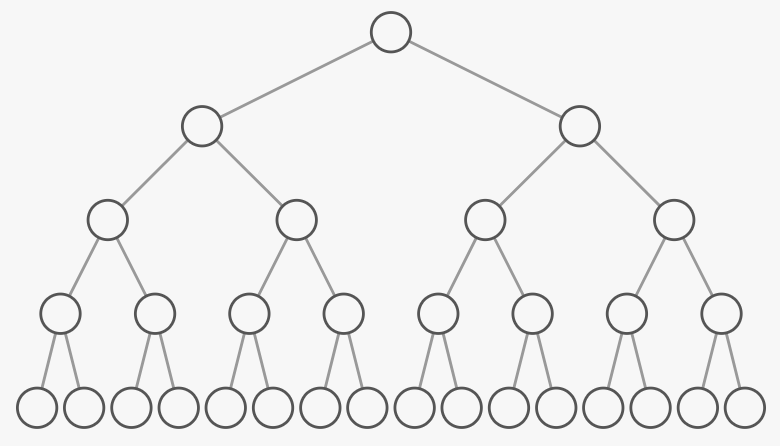

In a binary tree, each node has two or fewer children.

The tree above is special because each "level" or "tier" of the tree is full. There aren't any gaps. We call such a tree "perfect." One question we might ask is, if there are nodes in total, what's the tree's height ()? In other words, how many levels does the tree have? If we count the number of nodes on each level, we can notice that it successively doubles as we go:

That brings back our refrain, "how many times must we double 1 to get to ." But this time, we're not doubling 1 to get to ; is the total number of nodes in the tree. We're doubling 1 until we get to ... the number of nodes on the last level of the tree. How many nodes does the last level have? Look back at the diagram above. The last level has about half of the total number of nodes on the tree. If you add up the number of nodes on all the levels except the last one, you get about the number of nodes on the last level--1 less:

The exact formula for the number of nodes on the last level is:

Where does the come from? The number of nodes in our perfect binary tree is always odd. We know this because the first level always has 1 node, and the other levels always have an even number of nodes. Adding a bunch of even numbers always gives us an even number, and adding 1 to that result always gives us an odd number. Taking half of an odd number gives us a fraction. So if the last level had exactly half of our nodes, it would have to have a "half-node." But that's not a thing. Instead, it has the "rounded up" version of half of our odd nodes. In other words, it has the exact half of the one-greater-and-thus-even number of nodes . Hence .

So our height () is the same as "the number of times we have to double 1 to get to . So we can phrase this as a logarithm:

One adjustment: Consider a perfect, 2-level tree. There are 2 levels overall, but the "number of times we have to double 1 to get to 2" is just 1. Our height is in fact one more than our number of doublings. So we add 1:

Using some of our logarithm rules, this simplifies to .

Conventions with bases

Sometimes people don't include a base. In computer science, it's usually implied that the base is 2. So generally means . There's a specific notation for base 2 that's sometimes used: . So we could say , or (which comes up a lot in sorting). This notation is used a lot on Interview Cake, but it's worth noting that not everyone uses it.

In big O notation the base is considered a constant. So folks usually don't include it. People usually say , not . But people might still use the special notation , as in .