Linked Lists

Readings

Linked List

Quick Reference

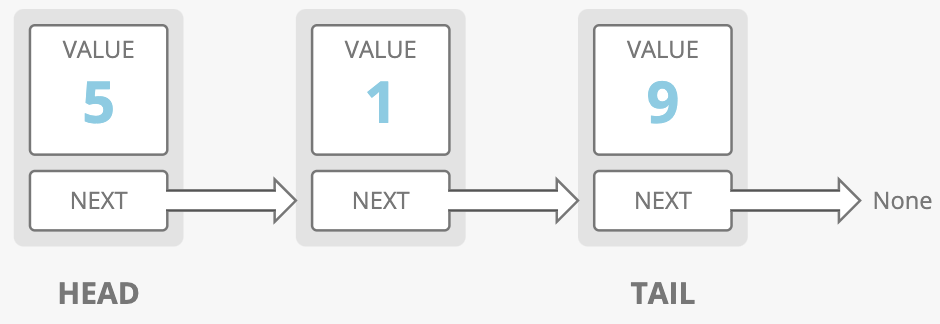

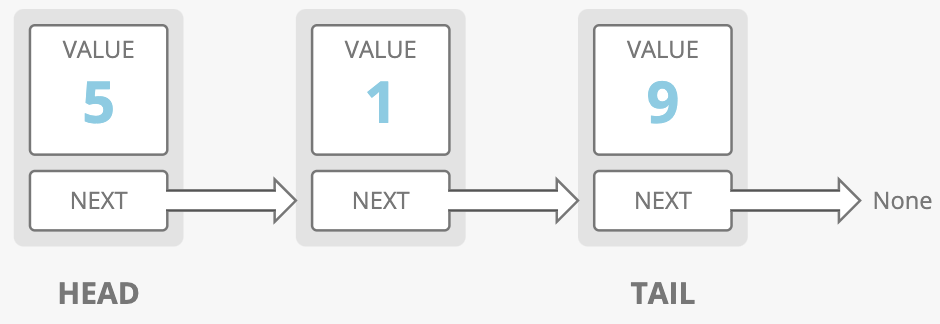

Description: Also stores things in order. Faster insertions and deletions than array but slower lookups (you have to "walk down" the whole list). A linked list organizes items sequentially, with each item storing a pointer to the next one. Picture a linked list like a chain of paperclips linked together. It's quick to add another paperclip to the top or bottom. It's even quick to insert one in the middle—-just disconnect the chain at the middle link, add the new paperclip, then reconnect the other half. An item in a linked list is called a node. The first node is called the head. The last node is called the tail.

Confusingly, sometimes people use the word tail to refer to "the whole rest of the list after the head." Unlike an array, consecutive items in a linked list are not necessarily next to each other in memory.

Visual description:

Strengths:

- Fast operations on the ends: Adding elements at either end of a linked list is . Removing the first element is also .

- Flexible size: There's no need to specify how many elements you're going to store ahead of time. You can keep adding elements as long as there's enough space on the machine.

Weaknesses:

- Costly lookups: To access or edit an item in a linked list, you have to take time to walk from the head of the list to the th item.

Uses:

- Stacks and queues only need fast operations on the ends, so linked lists are ideal.

Worst Case Analysis:

| Context | Big O |

|---|---|

| space | |

| prepend | |

| append | |

| lookup | |

| insert | |

| delete |

In JavaScript

Most languages (including JavaScript) don't provide a linked list implementation. Assuming we've already implemented our own, here's how we'd construct the linked list above:

const a = new LinkedListNode(5);

const b = new LinkedListNode(1);

const c = new LinkedListNode(9);

a.next = b;

b.next = c;

Doubly Linked Lists

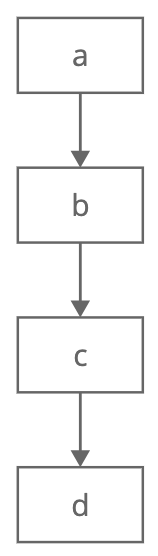

In a basic linked list, each item stores a single pointer to the next element. In a doubly linked list, items have pointers to the next and the previous nodes.

Doubly linked lists allow us to traverse our list backwards. In a singly linked list, if you just had a pointer to a node in the middle of a list, there would be no way to know what nodes came before it. Not a problem in a doubly linked list.

Not cache-friendly

Most computers have caching systems that make reading from sequential addresses in memory faster than reading from scattered addresses.

Array items are always located right next to each other in computer memory, but linked list nodes can be scattered all over.

So iterating through a linked list is usually quite a bit slower than iterating through the items in an array, even though they're both theoretically time.

Practice

Delete Node

Delete a node from a singly-linked list, given only a variable pointing to that node.

The input could, for example, be the variable b below:

class LinkedListNode(object):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.next = None

a = LinkedListNode('A')

b = LinkedListNode('B')

c = LinkedListNode('C')

a.next = b

b.next = c

delete_node(b)

Hint 1

It might be tempting to try to traverse the list from the beginning until we encounter the node we want to delete. But in this situation, we don't know where the head of the list is-—we only have a reference to the node we want to delete.

But hold on-—how do we even delete a node from a linked list in general, when we do have a reference to the first node?

Hint 2

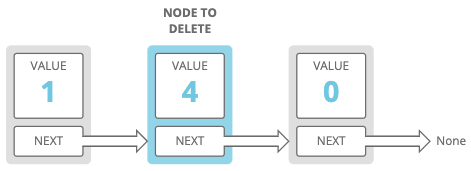

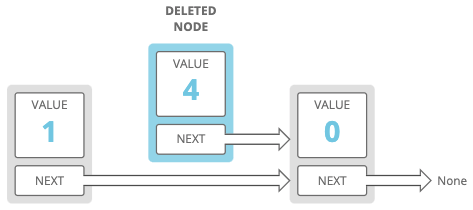

We'd change the previous node's pointer to skip the node we want to delete, so it just points straight to the node after it. So if these were our nodes before deleting a node:

These would be our nodes after our deletion:

Hint 3

So we need a way to skip over the current node and go straight to the next node. But we don't even have access to the previous node!

Other than rerouting the previous node's pointer, is there another way to skip from the previous pointer's value to the next pointer's value?

Hint 4

What if we modify the current node instead of deleting it?

Hint 5 (solution)

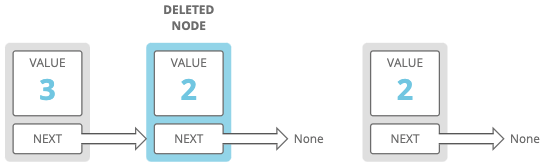

We take value and next from the input node's next node and copy them into the input node. Now the input node's previous node effectively skips the input node's old value!

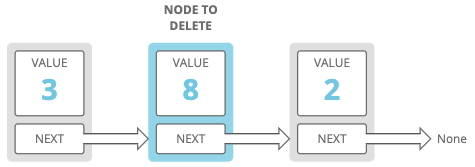

So for example, if this was our linked list before we called our function:

This would be our list after we called our function:

In some languages, like C, we'd have to manually delete the node we copied from, since we won't be using that node anymore. Here, we'll let JavaScript's garbage collector take care of it.

def delete_node(node_to_delete):

# Get the input node's next node, the one we want to skip to

next_node = node_to_delete.next

if next_node:

# Replace the input node's value and pointer with the next

# node's value and pointer. The previous node now effectively

# skips over the input node

node_to_delete.value = next_node.value

node_to_delete.next = next_node.next

else:

# Eep, we're trying to delete the last node!

raise Exception("Can't delete the last node with this technique!")

But be careful-—there are some potential problems with this implementation:

First, it doesn't work for deleting the last node in the list. We could change the node we're deleting to have a value of null, but the second-to-last node's next pointer would still point to a node, even though it should be null. This could work—-we could treat this last, "deleted" node with value null as a "dead node" or a "sentinel node," and adjust any node traversing code to stop traversing when it hits such a node. The trade-off there is we couldn't have non-dead nodes with values set to null. Instead we chose to throw an exception in this case.

Second, this technique can cause some unexpected side-effects. For example, let's say we call:

a = LinkedListNode(3)

b = LinkedListNode(8)

c = LinkedListNode(2)

a.next = b

b.next = c

delete_node(b)

There are two potential side-effects:

- Any references to the input node have now effectively been reassigned to its

nextnode. In our example, we "deleted" the node assigned to the variableb, but in actuality we just gave it a new value (2) and a newnext! If we had another pointer tobsomewhere else in our code and we were assuming it still had its old value (8), that could cause bugs. - If there are pointers to the input node's original next node, those pointers now point to a "dangling" node (a node that's no longer reachable by walking down our list). In our example above,

cis now dangling. If we changedc, we'd never encounter that new value by walking down our list from the head to the tail.

Complexity

time and space.

What We Learned

My favorite part of this problem is how imperfect the solution is. Because it modifies the list "in place" it can cause other parts of the surrounding system to break. This is called a "side effect."

In-place operations like this can save time and/or space, but they're risky. If you ever make in-place modifications in an interview, make sure you tell your interviewer that in a real system you'd carefully check for side effects in the rest of the code base.

Does This Linked List Have A Cycle?

You have a singly-linked list and want to check if it contains a cycle.

A singly-linked list is built with nodes, where each node has:

node.next-—the next node in the list.node.value-—the data held in the node. For example, if our linked list stores people in line at the movies,node.valuemight be the person's name.

For example:

class LinkedListNode(object):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.next = None

A cycle occurs when a node's next points back to a previous node in the list. The linked list is no longer linear with a beginning and end-—instead, it cycles through a loop of nodes.

Write a function contains_cycle() that takes the first node in a singly-linked list and returns a boolean indicating whether the list contains a cycle.

Hint 1

Because a cycle could result from the last node linking to the first node, we might need to look at every node before we even see the start of our cycle again. So it seems like we can't do better than runtime.

How can we track the nodes we've already seen?

Hint 2

Using a set, we could store all the nodes we've seen so far. The algorithm is simple:

- If the current node is already in our set, we have a cycle. Return

True. - If the current node is

Nonewe've hit the end of the list. ReturnFalse. - Else throw the current node in our set and keep going.

What are the time and space costs of this approach? Can we do better?

Hint 3

Our runtime is , the best we can do. But our space cost is also . Can we get our space cost down to by storing a constant number of nodes?

Hint 4

Think about a looping list and a linear list. What happens when you traverse one versus the other?

Hint 5

A linear list has an end-—a node that doesn't have a next node. But a looped list will run forever. We know we don't have a loop if we ever reach an end node, but how can we tell if we've run into a loop?

Hint 6

We can't just run our function for a really long time, because we'd never really know with certainty if we were in a loop or just a really long list.

Imagine that you're running on a long, mountainous running trail that happens to be a loop. What are some ways you can tell you're running in a loop?

Hint 7

One way is to look for landmarks. You could remember one specific point, and if you pass that point again, you know you're running in a loop. Can we use that principle here?

Hint 8

Well, our cycle can occur after a non-cyclical "head" section in the beginning of our linked list. So we'd need to make sure we chose a "landmark" node that is in the cyclical "tail" and not in the non-cyclical "head." That seems impossible unless we already know whether or not there's a cycle...

Think back to the running trail. Besides landmarks, what are some other ways you could tell you're running in a loop? What if you had another runner? (Remember, it's a singly-linked list, so no running backwards!)

Hint 9

A tempting approach could be to have the other runner stop and act as a "landmark," and see if you pass her again. But we still have the problem of making sure our "landmark" is in the loop and not in the non-looping beginning of the trail.

What if our "landmark" runner moves continuously but slowly?

Hint 10

If we sprint quickly down the trail and the landmark runner jogs slowly, we will eventually "lap" (catch up to) the landmark runner!

But what if there isn't a loop?

Hint 11

Then we (the faster runner) will simply hit the end of the trail (or linked list).

So let's make two variables, slow_runner and fast_runner. We'll start both on the first node, and every time slow_runner advances one node, we'll have fast_runner advance two nodes.

If fast_runner catches up with slow_runner, we know we have a loop. If not, eventually fast_runner will hit the end of the linked list and we'll know we don't have a loop.

This is a complete solution! Can you code it up?

Make sure the function eventually terminates in all cases!

Hint 12

Solution

We keep two pointers to nodes (we'll call these "runners"), both starting at the first node. Every time slow_runner moves one node ahead, fast_runner moves two nodes ahead.

If the linked list has a cycle, fast_runner will "lap" (catch up with) slow_runner, and they will momentarily equal each other.

If the list does not have a cycle, fast_runner will reach the end.

def contains_cycle(first_node):

# Start both runners at the beginning

slow_runner = first_node

fast_runner = first_node

# Until we hit the end of the list

while fast_runner is not None and fast_runner.next is not None:

slow_runner = slow_runner.next

fast_runner = fast_runner.next.next

# Case: fast_runner is about to "lap" slow_runner

if fast_runner is slow_runner:

return True

# Case: fast_runner hit the end of the list

return False

Complexity

time and space.

The runtime analysis is a little tricky. The worst case is when we do have a cycle, so we don't return until fast_runner equals slow_runner. But how long will that take?

First, we notice that when both runners are circling around the cycle fast_runner can never skip over slow_runner. Why is this true?

Suppose fast_runner had just skipped over slow_runner. fast_runner would only be 1 node ahead of slow_runner, since their speeds differ by only 1. So we would have something like this:

[ ] -> [s] -> [f]

What would the step right before this "skipping step" look like? fast_runner would be 2 nodes back, and slow_runner would be 1 node back. But wait, that means they would be at the same node! So fast_runner didn't skip over slow_runner! (This is a proof by contradiction.)

Since fast_runner can't skip over slow_runner, at most slow_runner will run around the cycle once and fast_runner will run around twice. This gives us a runtime of .

For space, we store two variables no matter how long the linked list is, which gives us a space cost of .

Bonus

- How would you detect the first node in the cycle? Define the first node of the cycle as the one closest to the head of the list.

- Would the program always work if the fast runner moves three steps every time the slow runner moves one step?

- What if instead of a simple linked list, you had a structure where each node could have several "

next" nodes? This data structure is called a "directed graph." How would you test if your directed graph had a cycle?

What We Learned

Some people have trouble coming up with the "two runners" approach. That's expected—-it's somewhat of a blind insight. Even great candidates might need a few hints to get all the way there. And that's fine.

Remember that the coding interview is a dialogue, and sometimes your interviewer expects she'll have to offer some hints along the way.

One of the most impressive things you can do as a candidate is listen to a hint, fully understand it, and take it to its next logical step. Interview Cake gives you lots of opportunities to practice this. Don't be shy about showing lots of hints on our exercises—-that's what they're there for!

Reverse A Linked List

Hooray! It's opposite day. Linked lists go the opposite way today.

Write a function for reversing a linked list. Do it in place.

Your function will have one input: the head of the list.

Your function should return the new head of the list.

Here's a sample linked list node class:

class LinkedListNode(object):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.next = None

Hint 1

Our first thought might be to build our reversed list "from the beginning," starting with the head of the final reversed linked list.

The head of the reversed list will be the tail of the input list. To get to that node we'll have to walk through the whole list once ( time). And that's just to get started.

That seems inefficient. Can we reverse the list while making just one walk from head to tail of the input list?

Hint 2

We can reverse the list by changing the next pointer of each node. Where should each node's next pointer...point?

Hint 3

Each node's next pointer should point to the previous node.

How can we move each node's next pointer to its previous node in one pass from head to tail of our current list?

Hint 4 (solution)

Solution

In one pass from head to tail of our input list, we point each node's next pointer to the previous item.

The order of operations is important here! We're careful to copy current_node.next into next before setting current_node.next to previous_node. Otherwise "stepping forward" at the end could actually mean stepping back to previous_node!

def reverse(head_of_list):

current_node = head_of_list

previous_node = None

next_node = None

# Until we have 'fallen off' the end of the list

while current_node:

# Copy a pointer to the next element

# before we overwrite current_node.next

next_node = current_node.next

# Reverse the 'next' pointer

current_node.next = previous_node

# Step forward in the list

previous_node = current_node

current_node = next_node

return previous_node

We return previous_node because when we exit the list, current_node is None. Which means that the last node we visited—-previous_node-—was the tail of the original list, and thus the head of our reversed list.

Complexity

time and space. We pass over the list only once, and maintain a constant number of variables in memory.

Bonus

This in-place reversal destroys the input linked list. What if we wanted to keep a copy of the original linked list? Write a function for reversing a linked list out-of-place.

What We Learned

It's one of those problems where, even once you know the procedure, it's hard to write a bug-free solution. Drawing it out helps a lot. Write out a sample linked list and walk through your code by hand, step by step, running each operation on your sample input to see if the final output is what you expect. This is a great strategy for any coding interview question.

Kth to Last Node in a Singly-Linked List

You have a linked list and want to find the th to last node.

Write a function kth_to_last_node() that takes an integer and the head_node of a singly-linked list, and returns the th to last node in the list.

For example:

class LinkedListNode:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.next = None

a = LinkedListNode("Angel Food")

b = LinkedListNode("Bundt")

c = LinkedListNode("Cheese")

d = LinkedListNode("Devil's Food")

e = LinkedListNode("Eccles")

a.next = b

b.next = c

c.next = d

d.next = e

# Returns the node with value "Devil's Food" (the 2nd to last node)

kth_to_last_node(2, a)

Hint 1

It might be tempting to iterate through the list until we reach the end and then walk backward nodes.

But we have a singly linked list! We can’t go backward. What else can we do?

Hint 2

What if we had the length of the list?

Hint 3

Then we could calculate how far to walk, starting from the head, to reach the th to last node.

If the list has nodes:

And our target is the th to last node:

The distance from the head to the target is :

Well, we don't know the length of the list (). But can we figure it out?

Hint 4

Yes, we could iterate from the head to the tail and count the nodes!

Can you implement this approach in code?

Hint 5

def kth_to_last_node(k, head):

# Step 1: get the length of the list

# Start at 1, not 0

# else we'd fail to count the head node!

list_length = 1

current_node = head

# Traverse the whole list,

# counting all the nodes

while current_node.next:

current_node = current_node.next

list_length += 1

# Step 2: walk to the target node

# Calculate how far to go, from the head,

# to get to the kth to last node

how_far_to_go = list_length - k

current_node = head

for i in range(how_far_to_go):

current_node = current_node.next

return current_node

What are our time and space costs?

Hint 6

time and space, where is the length of the list.

More precisely, it takes steps to get the length of the list, and another steps to reach the target node. In the worst case , so we have to walk all the way from head to tail again to reach the target node. This is a total of steps, which is .

Can we do better?

Hint 7

Mmmmaaaaaaybe.

The fact that we walk through our whole list once just to get the length, then walk through the list again to get to the th to last element sounds like a lot of work. Perhaps we can do this in just one pass?

Hint 8

What if we had like a "stick" that was nodes wide. We could start it at the beginning of the list so that the left side of the stick was on the head and the right side was on the th node.

Then we could slide the stick down the list...

until the right side hit the end. At that point, the left side of the stick would be on the th to last node!

How can we implement this? Maybe it'll help to keep two pointers?

Hint 9

We can allocate two variables that'll be references to the nodes at the left and right sides of the "stick"!

def kth_to_last_node(k, head):

left_node = head

right_node = head

# Move right_node to the kth node

for _ in range(k - 1):

right_node = right_node.next

# Starting with left_node on the head,

# move left_node and right_node down the list,

# maintaining a distance of k between them,

# until right_node hits the end of the list

while right_node.next:

left_node = left_node.next

right_node = right_node.next

# Since left_node is k nodes behind right_node,

# left_node is now the kth to last node!

return left_node

This'll work, but does it actually save us any time?

Hint 10 (solution)

Solution

We can think of this two ways.

First approach: use the length of the list.

- walk down the whole list, counting nodes, to get the total

list_length. - subtract from the

list_lengthto get the distance from the head node to the target node (the kth to last node). - walk that distance from the head to arrive at the target node.

def kth_to_last_node(k, head):

if k < 1:

raise ValueError(

'Impossible to find less than first to last node: %s' % k

)

# Step 1: get the length of the list

# Start at 1, not 0

# else we'd fail to count the head node!

list_length = 1

current_node = head

# Traverse the whole list,

# counting all the nodes

while current_node.next:

current_node = current_node.next

list_length += 1

# If k is greater than the length of the list, there can't

# be a kth-to-last node, so we'll return an error!

if k > list_length:

raise ValueError(

'k is larger than the length of the linked list: %s' % k

)

# Step 2: walk to the target node

# Calculate how far to go, from the head,

# to get to the kth to last node

how_far_to_go = list_length - k

current_node = head

for i in range(how_far_to_go):

current_node = current_node.next

return current_node

Second approach: maintain a -wide "stick" in one walk down the list.

- Walk one pointer nodes from the head. Call it

right_node. - Put another pointer at the head. Call it

left_node. - Walk both pointers, at the same speed, towards the tail. This keeps a distance of between them.

- When

right_nodehits the tail,left_nodeis on the target (since it's nodes from the end of the list).

def kth_to_last_node(k, head):

if k < 1:

raise ValueError(

'Impossible to find less than first to last node: %s' % k

)

left_node = head

right_node = head

# Move right_node to the kth node

for _ in range(k - 1):

# But along the way, if a right_node doesn't have a next,

# then k is greater than the length of the list and there

# can't be a kth-to-last node! we'll raise an error

if not right_node.next:

raise ValueError(

'k is larger than the length of the linked list: %s' % k

)

right_node = right_node.next

# Starting with left_node on the head,

# move left_node and right_node down the list,

# maintaining a distance of k between them,

# until right_node hits the end of the list

while right_node.next:

left_node = left_node.next

right_node = right_node.next

# Since left_node is k nodes behind right_node,

# left_node is now the kth to last node!

return left_node

In either approach, make sure to check if k is greater than the length of the linked list! That's bad input, and we'll want to raise an error.

Complexity

Both approaches use time and space.

But the second approach is fewer steps since it gets the answer "in one pass," right? Wrong.

In the first approach, we walk one pointer from head to tail (to get the list's length), then walk another pointer from the head node to the target node (the th to last node).

In the second approach, right_node also walks all the way from head to tail, and left_node also walks from the head to the target node.

So in both cases, we have two pointers taking the same steps through our list. The only difference is the order in which the steps are taken. The number of steps is the same either way.

However, the second approach might still be slightly faster, due to some caching and other optimizations that modern processors and memory have.

Let's focus on caching. Usually when we grab some data from memory (for example, info about a linked list node), we also store that data in a small cache right on the processor. If we need to use that same data again soon after, we can quickly grab it from the cache. But if we don't use that data for a while, we're likely to replace it with other stuff we've used more recently (this is called a "least recently used" replacement policy).

Both of our algorithms access a lot of nodes in our list twice, so they could exploit this caching. But notice that in our second algorithm there's a much shorter time between the first and second times that we access a given node (this is sometimes called "temporal locality of reference"). Thus it seems more likely that our second algorithm will save time by using the processor's cache! But this assumes our processor's cache uses something like a "least recently used" replacement policy—-it might use something else. Ultimately the best way to really know which algorithm is faster is to implement both and time them on a few different inputs!

Bonus

Can we do better? What if we expect to be huge and to be pretty small? In this case, our target node will be close to the end of the list...so it seems a waste that we have to walk all the way from the beginning twice.

Can we trim down the number of steps in the "second trip"? One pointer will certainly have to travel all the way from head to tail in the list to get the total length...but can we store some "checkpoints" as we go so that the second pointer doesn't have to start all the way at the beginning? Can we store these "checkpoints" in constant space? Note: this approach only saves time if we know that our target node is towards the end of the list (in other words, is much larger than ).

What We Learned

We listed two good solutions. One seemed to solve the problem in one pass, while the other took two passes. But the single-pass approach didn't take half as many steps, it just took the same steps in a different order.

So don't be fooled: "one pass" isn't always fewer steps than "two passes." Always ask yourself, "Have I actually changed the number of steps?"