System Design

Practice

URL Shortener

You know, like bit.ly.

Let's call it ca.ke!

Step 1 is to scope the project. System design questions like this are usually intentionally left open-ended, so you have to ask some questions and make some decisions about exactly what you're building to get on the same page as your interviewer.

So, what are we building? What features might we need?

Hint 1

Features

Is this a full web app, with a web interface? No, let's just build an API to start.

Since it's an API, do we need authentication or user accounts or developer keys? No, let's just make it open to start.

Can people modify or delete links? Let's leave that out for now.

If people can't delete links...do they persist forever? Or do we automatically remove old ones? First, it's worth considering what policies we could use for removing old ones:

- We could remove links that were created some length of time ago...like 6 months.

- We could remove links that haven't been visited in some length of time...like 6 months.

(2) seems less frustrating than (1). Are there cases where (2) could still frustrate users? If a link is on the public web, it's likely to get hit somewhat regularly, at least by spiders. But what if it's on the private web (e.g. an internal "resources" page on a private university intranet)? Or...what if someone printed a bunch of pamphlets that had the URL on it, didn't give out any pamphlets for a few months, then started giving them out again? That seems like a pretty reasonable thing that might happen (putting a URL on a printed piece of paper is a great reason to use a link shortener!) and having the link suddenly stop working would be quite frustrating for the user. Worse, what if a book already had the shortlink printed in a million copies? So let's let links exist forever.

Should we let people choose their shortlink, or just always auto-generate it? For example, say they want ca.ke/parkers-resume. Let's definitely support that.

Do we need analytics, so people can see how many people are clicking on a link, etc? Hmmm, good idea. But let's leave it out to start.

It's okay if your list of features was different from ours. Let's proceed with these requirements so we're working on the same problem.

Next step: Design goals. If we're designing something, we should know what we're optimizing for! What are we optimizing for?

Hint 2

Design Goals

Here's what we came up with:

- We should be able to store a lot of links, since we're not automatically expiring them.

- Our shortlinks should be as short as possible. The whole point of a link shortener is to make short links! Having shorter links than our competition could be a business advantage.

- Following a shortlink should be fast.

- The shortlink follower should be resilient to load spikes. One of our links might be the top story on Reddit, for example.

It's worth taking a moment to really think about the order of our goals. Sometimes design goals are at odds with each other (to do a better job of one, we need to do a worse job of another). So it's helpful to know which goals are more important than others.

It's okay if your list wasn't just like ours. But to get on the same page, let's move forward with these design goals.

Next step: building the data model. Think about the database schema or the models we'll want. What things do we need to store, and how should they relate to each other? This is the part where we answer questions like "is this a many-to-many or a one-to-many?" or "should these be in the same table or different tables?"

Hint 3

Data Model

It's worthwhile to be careful about how we name things. This'll help us communicate clearly with our interviewer, and it'll show that we care about using descriptive and consistent names! Many interviewers look for this.

Let's call our main entity a Link. A Link is a mapping between a shortLink on our site, and a longLink, where we redirect people when they visit the shortLink.

Link

- shortLink

- longLink

The shortLink could be one we've randomly generated, or one a user chose.

Of course, we don't need to store the full ShortLink URL (e.g. ca.ke/mysite), we just need to store the "slug"—-the part at the end (e.g. "mysite").

So let's rename the shortLink field to "slug."

Link

- slug

- longLink

Now the name longLink doesn't make as much sense without shortLink. So let's change it to destination.

Link

- slug

- destination

And let's call this whole model/table ShortLink, to be a bit more specific.

ShortLink

- slug

- destination

Investing time in carefully naming things from the beginning is always impressive in an interview. A big part of code readability is how well things are named!

Next: sketching the code. Don't get hung up on the details here-—pseudocode is fine.

Think of this part as sprinting to a naive first draft design, so you and your interviewer can get on the same page and have a starting point for optimizing. There may be things that come up as you go that are clearly "tricky issues" that need to be thought through. Feel free to skip these as you go—-just jot down a note to come back to them later.

Our main goal here is to come up with a skeleton to start building things out from. Think about what endpoints/views we'll need, and what each one will have to do.

Hint 4

Views/Pages/Endpoints

First, let's make a way to create a ShortLink.

Since we're making an API, let's make it REST-style. If REST is one of those "I've heard it a bunch but only half know what it means" things for you, I highly recommend reading up on it.

In normal REST style, our endpoint for creating a ShortLink should be named after the entity we're creating. Versioning apis is also a reasonable thing to do. So let's put our creation endpoint at ca.ke/api/v1/shortlink.

To create a new ShortLink, we'll send a POST request there. Our POST request will include one required argument: the destination where our ShortLink will point. It'll also optionally take a slug argument. If no slug is provided, we'll generate one. The response will contain the newly-created ShortLink, including its slug and destination.

$ curl --data '{"destination": "interviewcake.com"}' https://ca.ke/api/v1/shortlink

{

"slug": "ae8uFt",

"destination": "interviewcake.com"

}

In usual REST style, we should allow GET, PUT, PATCH, and DELETE requests as well to read, modify, and delete links. But since that's not a requirement yet, we'll just reject non-POST requests with an error 501 ("not implemented") for now.

So our endpoint might look something like this (pseudocode):

def shortlink(request):

if request['method'] is not 'POST':

return Response(501) # HTTP 501 NOT IMPLEMENTED

destination = request['data']['destination']

if 'slug' in request['data']:

# If they included a slug, use that

slug = request['data']['slug']

else:

# Else, make them one

slug = generate_random_slug()

DB.insert({'slug': slug, 'destination': destination})

response_body = { 'slug': slug }

return Response(200, json.dumps(response_body)) # HTTP 200 OK

Of course, we haven't defined exactly how generateRandomSlug() works. Considering it a bit, it quickly becomes clear this is a pretty tangled issue. We'll have to figure out:

- What characters can we use in randomly generated slugs? More possible characters means more possible random slugs without making our shortlinks longer. But what characters are allowed in URLs?

- How do we ensure a randomly generated slug hasn't already been used? Or if there is such a collision, how do we handle it?

So let's jot down these questions, put them aside, and come back to them after we're done sketching our general app structure.

Second, let's make a way to follow a ShortLink. That's the whole point, after all!

Our shortened URLs should be as short as possible. So as mentioned before, we'll give them this format: ca.ke/$slug.

Where $slug is the slug (either auto-generated by us or specified by the user). We could make it clearer that this is a redirect endpoint, by using a format like ca.ke/r/$slug, for example. But that adds 2 precious characters of length to our shortlink URLs!

One potential challenge here: if/when we build a web app for our service, we'll need some way of differentiating our own pages from shortlinks. For example, if we want an about page at ca.ke/about, our back-end will need to know "about" isn't just a shortlink slug. In fact, we might want to "reserve" or "block" shortlinks for pages we think we might need, so users don't grab URLs we might want for our own site. Alternately we could just say our pages have paths that're always prefixed with something, like /w/. For example, ca.ke/w/about.

The code for the redirection endpoint is pretty simple:

def redirect(request):

destination = DB.get({'slug': request['path']})['destination']

return Response(302, destination)

Next: slug generation. Let's return to those questions we came up with about slugs. How long should they be, what characters should we allow, and how should we handle random slug collisions?

Hint 5

Slug Generation

A note about methodology: Our default process for answering questions like this is often "make a reasonable guess, brainstorm potential issues, and revise." That's fine, but sometimes it feels more organized and impressive to do something more like "brainstorm design goals, then design around those goals." So we'll do that.

Let's look back up at the design goals we came up with earlier. The first two are immediately relevant to this problem:

- We should be able to store a lot of links.

- Our

shortlinksshould be as short as possible.

Looking at a few examples, we can quickly notice that the more characters we allow in our shortlinks, the more different ShortLinks we can have without making our ShortLinks longer. Specifically, if we allow different characters, for -character-long slugs we have distinct possibilities.

How did we get that math?

We drew out a few examples and looked for patterns.

It helps to start with small numbers. Suppose we only allowed 2 different characters for our slugs: 'a' and 'b', How many possible 1-character slugs would we have? 2: 'a' and 'b'.

How many possible 2-character slugs? Well, we have 2 possibilities for the first character, and for each of those 2 possible first characters, we have 2 possible second characters. That's possibilities overall.

How many possible 3-character slugs? 2 possibilities for the first character, and for each of those 2 possible first characters, we have 2 possible second characters, and for each of those possible first and second characters, another 2 possible third characters. That's possibilities overall.

Looks like this is a multiplication thing. Or in fact, a power thing. In general, we have possible -character slugs, if we only allow 2 possible choices (a and b) for each character.

And if we want to allow different possible characters, instead of just 2? possibilities for an -character-long slug.

So if we're trying to accommodate as many slugs as possible, we should allow as many characters as we can! So let's do this:

- Figure out the max set of characters we can allow in our random shortlinks.

- Figure out how many distinct shortlinks we want to accommodate.

- Figure out how long our shortlinks must be to accommodate that many distinct possibilities.

Sketching a process like this before jumping in is hugely impressive. It shows organized, methodical thinking. Whenever you're not sure how to proceed, take a step back and try to write out a process for getting to the bottom of things. It's fine if you end up straying from your plan—-it'll still help you organize your thinking.

What characters can we allow in our randomly-generated slugs?

What are the constraints on ? Let's think about it:

- We should only use characters that are actually allowed in URLs.

- We should probably only pick characters that are relatively easy to type on a keyboard. Remember the use case we talked about where people are typing in a

ShortLinkthat they're reading off a piece of paper?

So, what characters are allowed in URLs? It's okay to not know the answer off the top of your head. But you should be able to tell your interviewer that you know how to figure it out! Googling or searching on Stack Overflow is a fine answer. It's even cooler to say, "I'm sure this is defined in an RFC somewhere."

What's an RFC? RFC stands for "request for comments." The first ones are from 1969 (back in the day of ARPANET, the precursor to the internet), and we still get new ones every year. RFCs define lots of conventions for how internet communications work. Like how status code 404 means "not found". Hilariously, some of the latest RFCs spec a custom XML vocabulary for writing RFCs. Yo dog. Also there's this one on the history of calling variables "Foo." Easy to get lost browsing these...

It turns out the answer is "only alphanumerics, the special characters $-_.+!*'(), and reserved characters used for their reserved purposes may be used unencoded within a URL" (RFC 1738). "Reserved characters" with "reserved purposes" are characters like '?', which marks the beginning of a query string, and '#', which marks the beginning of a fragment/anchor. We definitely shouldn't use any of those. If we allowed '?' in the beginning of our slug, the characters after it would be interpreted as part of the query string and not part of the slug!

So just alphanumerics and the "special characters" $-_.+!*'(),. Are accented alphabetical characters allowed? No, according to RFC 3986.

What about uppercase and lowercase? Domains aren't case-sensitive (so google.com and Google.com will always go to the same place), but the path portion of a URL is case-sensitive. If I query parker.com/foo and parker.com/Foo, I'm requesting different documents (although, as a site owner, I may choose to return the same document in response to both requests). So yes, lowercase and capital versions of the same letter can be treated as different characters in our slugs.

Okay, so it seems like the set of allowed characters is A-Z, a-z, 0-9, and $-_.+!*'(),. The apostrophe character seems a little iffy, since sometimes URLs are surrounded by single quotes in HTML documents. So let's pull that one.

In fact, in keeping with point (2) above about ease of typing, let's pull all the "special characters" from our list. It seems like a small loss on character count (8 characters) in exchange for a big win on readability and typeability. If we find ourselves wanting those extra characters, we can add add 'em back in.

Ah, but what if a user is specifying her own slug? She might want to use underscores, or dashes, or parentheses...so let's say for user-specified slugs, we allow $-_.+!*(), (still no apostrophe).

While we're on the topic of making URLs easy to type, we might want to consider constraining our character set to clear up common ambiguities. For example, not allowing both uppercase letter O and number 0. Or lowercase letter l and number 1. Font choice can help reduce these ambiguities, but we don't have any control over the fonts people use to display our shortlinks. This is a worthwhile consideration, but at the moment it's adding complexity to a question we're still trying to figure out. So let's just mention it and say, "This is something we want to keep an eye on for later, but let's put it aside for now." Your interviewer understands that you can't accommodate everything in your initial design, but she'll appreciate you showing an ability to anticipate what problems may come up in the user experience.

Okay, so with a-z, A-Z, and 0-9, we have 26 + 26 + 10 = 62 possible characters in our randomly-generated slugs. And for user-generated slugs, we have another 10 characters ($-_.+!*(),), for 72 total.

How many distinct slugs do we need?

About how many slugs do we need to be able to accommodate? This is a good question to ask your interviewer. She may want you to make a reasonable choice yourself. There's no one right answer; the important thing is to show some organized thinking.

Here's one way to come up with a ballpark estimate: about how many new slugs might we create on a busy day? Maybe 100,000 per minute? Hard to imagine more than that. That's million new links a day. 52.5 billion a year. What's a number of years that feels like "almost forever"? I'd say 100. So that's 5.2 trillion slugs. That seems sufficiently large. It's pretty dependent on the accuracy of our estimate of 100,000 per minute. But it seems to be a pretty reasonable ceiling, and a purposefully high one. If we can accommodate that many slugs, we expect we'll be able to keep handing out random slugs effectively indefinitely.

How short can we make our slugs while still getting enough distinct possibilities?

Let's return to the formula we came up with before: with a -character-long alphabet and slugs of length , we get possible slugs. We want ~5 trillion possible slugs. And we decided on a 62-character alphabet. So trillion. We just have to solve for .

We might know that we need to take a logarithm to solve for . But even if we know that, this is a tricky thing to eyeball. If we're in front of a computer or phone, we can just plug it in to wolfram alpha. Turns out the answer is . So 7 characters gets us most of the way to our target number of distinct possibilities.

It's worth checking how many characters we could save by allowing $-_.+!*(), as well. So trillion. We get . Including the special characters would save us something like .3 characters on our slug length.

Is it worth it? Of course, there's no such thing as a fraction of a character. If we really had to accommodate at least 5.2 trillion random slugs, we'd have to round up, which would mean 7.09 would round up to 8-character slugs for our 62-character alphabet (not including special characters) and 6.8 would round up to 7-character slugs for our 72-character alphabet (including special characters).

But we don't really have to accommodate 5.2 trillion or more slugs. 5.2 trillion was just a ballpark estimate—-and it was intended to be a high ceiling on how many slugs we expect to get. So let's stick with our first instinct to remove those special characters for readability purposes, and let's choose 7 characters for our slugs.

At a glance, looks like bit.ly agrees with our choices! They seem to use the same alphabet as us (A-Z, a-z, and 0-9) and use 7 characters for each randomly-generated slug.

For some added potential brevity, and some added possible random slugs, we could also allow for random slugs with fewer than 7 characters. How many additional random slugs would that get us?

If you're a whiz with mathematical series, you might know intuitively that the sum of these fewer-than-7-character slugs will be far less than the 7-character slugs. We can actually compute this to confirm.

(for 6-char slugs), plus (for 5-char slugs), plus (for 4-char slugs) plus plus plus 62. About 57 billion random slugs. Which isn't that much in comparison to 5.2 trillion-—it's two orders of magnitude less.

Since this doesn't win us much, let's skip it for now and only use exactly-7-character random slugs.

One interesting lesson here: going from 6 characters to 7 characters gave us a two orders of magnitude leap in our number of possible slugs. Going from 7 characters to 8 will give us another two orders of magnitude. So if and when we do start running out of 7-character random slugs, allowing just 1 more character will dramatically push back the point where we run out of random slugs.

Okay, we know the characters we'll use for slugs. And we know how many characters we'll use. Next: how do we generate a random slug?

Hint 6

We could just make a random choice for each character:

def generate_random_slug():

alphabet = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789"

num_chars = 7

return ''.join([random.choice(alphabet) for _ in range(num_chars)])

But how do we ensure slugs are unique? Two general strategies:

- "Re-roll" when we hit an already-used slug

- Adjust our slug generation strategy to only ever give us un-claimed slugs.

If we're serious about our first 2 design goals (short slugs, and accommodating many different slugs), option (2) is clearly better than option (1). Why? As we have more and more slugs in our database, we'll get more and more collisions. For example, when we're 3/4 of the way through our set of possible 7-character slugs, we'd expect to have to make four "rolls" before arriving at a slug that isn't taken already. And it'll just keep going up from there.

So let's try to come up with a strategy for option (2). How could we do it?

The answer is base conversion.

Using base conversion to generate slugs

We usually use base-10 numbers, which allow 10 possible numerals: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9.

Binary is base-2 and has 2 possible numerals: 0 and 1.

Our random slug alphabet has 62 possible numerals (A-Z, a-z, and 0-9). So we can think of each of our possible "random" slugs as a unique number, expressed in base-62.

So let's keep track of a global current_random_slug_id. When a request for a new random slug comes in, we simply convert that number to base-62 (using our custom numeral set) and return it. Oh, and we increment the current_random_slug_id, in preparation for the next request for a random slug.

def generate_random_slug():

global current_random_slug_id

slug = base_conversion(current_random_slug_id, base_62_alphabet)

current_random_slug_id += 1

return slug

Where should we store our current_random_slug_id? We can keep it in memory on our web server, perhaps with a regular writethrough to the database, to make it persistent even if the web server crashes. But what if we have multiple front-end web servers?

How do we do the base conversion? This is easiest to show by example.

Take the number 125 in base 10.

It has a 1 in the 100s place, a 2 in the 10s place, and a 5 in the 1s place. In general, the places in a base-10 number are:

- etc

The places in a base-62 number are:

- etc$

So to convert 125 to base-62, we distribute that 125 across these base-62 "places." The highest "place" that can take some is , which is 62.125/62 is 2, with a remainder of 1. So we put a 2 in the 62's place and a 1 in the 1's place. So our answer is 21.

What about a higher number—-say, 7,912?

Now we have enough to put something in the 3,844's place (the 's place). 7,912 / 3,844 is 2 with a remainder of 224. So we put a 2 in the 3,844's place, and we distribute that remaining 224 across the remaining places-—the 62's place and the 1's place. 224 / 62 is 3 with a remainder of 38. So we put a 3 in the 62's place and a 38 in the 1's place. We have this three-digit number: 2 3 38.

Now, that "38" represents one numeral in our base-62 number. So we need to convert that 38 into a specific choice from our set of numerals: a-z, A-Z, and 0-9.

Let's number each of our 62 numerals, like so:

0: 0,

1: 1,

2: 2,

3: 3,

...

10: a,

11: b,

12: c,

...

36: A,

37: B,

38: C,

...

61: Z

As you can see, our "38th" numeral is "C." So we convert that 38 to a "C." That gives us 23C.

Can we convert from slugs back to numbers? Yep, easy. Take 23C, for example. Translate the numerals back to their id numbers, so we get 2 3 38. That 2 is in the 3844's place, so we take 2 3844. That 3 is in the 62's place, so we take 3 62. That 38 is in the 1's place, so we take 38 * 1. We add up all those results to get our original 7,912.

One potential issue: the current_random_slug_id could be shorter than 7 digits in base-62. We could pad the generate slug with zeros to force it to be exactly 7 characters. Or we could simply accept shorter random slugs—-we'd just need to make sure our function that converts slugs back to numbers doesn't choke when the slug is fewer than 7 characters.

Another issue is that the current_random_slug_id could give us something that a user has already claimed as a user-generated slug. We'll need to check for that, and if it happens we'll just increment the current_random_slug_id and try again (and again, potentially, until we hit a "random" slug that hasn't been used yet).

def generate_random_slug():

global current_random_slug_id

while True:

slug = base_conversion(current_random_slug_id, base_62_alphabet)

current_random_slug_id += 1

# Make sure the slug isn't already used

existing = DB.get({'slug': slug})

if not existing:

return slug

Okay, this'll work! What's next? Let's look back at our design goals!

- We should be able to store a lot of links.

- Our shortlinks should be as short as possible.

- Following a shortlink should be fast.

- The shortlink follower should be resilient to load spikes.

We're all set on (1) and (2)! Let's start tackling (3) and (4). How do we scale our link follower to be fast and resilient to load spikes?

Beware of premature optimization! That always looks bad. Don't just jump around random ideas for optimizations. Instead, focus on asking yourself which thing is likely to bottleneck first and optimizing around that.

Hint 7

The database read to get the destination for the given slug is certainly going to be our first bottleneck. In general, database operations usually bottleneck before business logic.

To figure out how to get these reads nice and fast, we should get specific about how we're storing our shortlinks. To start, what kind of database should we use?

Hint 8

Database choice is a very broad issue. And it's a contentious one. There are lots of different opinions about how to approach this. Here's how we'll do it:

Broadly (this is definitely a simplification), there are two main types of databases these days:

- Relational databases (RDBMs) like MySQL and Postgres.

- "NoSQL"-style databases like BigTable and Cassandra.

In general (again, this is a simplification), relational databases are great for systems where you expect to make lots of complex queries involving joins and such—-in other words, they're good if you're planning to look at the relationships between things a lot. NoSQL databases don't handle these things quite as well, but in exchange they're faster for writes and simple key-value reads.

Looking at our app, it seems like relational queries aren't likely to be a big part of our app's functionality, even if we added a few of the obvious next features we might want. So let's go with NoSQL for this.

Which NoSQL database do we use? Lots of options, each with their own pros and cons. Let's keep our discussion and pseudocode generic for now.

We might consider adding an abstraction layer between our application and the database, so that we can change over to a new one if our needs change or if some new hotness comes out.

Okay, so we have our data in a NoSQL-type database. How do we un-bottleneck database reads?

Hint 9 (solution)

The first step is to make sure we're indexing the right way. In a NoSQL context, that means carefully designing our keys. In this case, the obvious choice is right: making the key for each row in the ShortLink table be the slug.

If we used a SQL-type database like MySQL or Postgres, we usually default to having our key field be a standard auto-incrementing integer called "id" or "index." But in this case, because we know that slugs will be unique, there's no need for an integer id—-the slug is enough of a unique identifier.

BUT here's where it gets clever: what if we represented the slug as an auto-incrementing integer field? We'd just have to use our base conversion function to convert them to slugs! This would also give us tracking of our global current_random_slug_id for free-—MySQL would keep track of the highest current id in the table when it auto increments. Careful though: user-generated slugs throw a pretty huge monkey wrench into things with this strategy! How can you maintain uniqueness across user-generated and randomly-generated slugs without breaking the auto-incrementing ids for randomly-generated slugs?

How else can we speed up database reads?

We could put as much of the data in memory as possible, to avoid disk seeks.

This becomes especially important when we start getting a heavy load of requests to a single link, like if one of our links is on the front page of Reddit. If we have the redirect URL right there in memory, we can process those redirects quickly.

Depending on the database we use, it might already have an in-memory cache system. To get more links in memory, we may be able to configure our database to use more space for its cache.

If reads are still slow, we could research adding a caching layer, like memcached. Importantly, this might not save us time on reads, if the cache on the database is already pretty robust. It adds complexity—-we now have two sources of truth, and we need to be careful to keep them in sync. For example, if we let users edit their links, we need to push those edits to both the database and the cache. It could also slow down reads if we have lots of cache misses.

If we did add a caching layer, there are a few things we could talk about:

- The eviction strategy. If the cache is full, what do we remove to make space? The most common answer is an LRU ("least recently used") strategy.

- Sharding strategy. Sharding our cache lets us store more stuff in memory, because we can use more machines. But how do we decide which things go on which shard? The common answer is a "hash and mod strategy"-—hash the key, mod the result by the number of shards, and you get a shard number to send your request to. But then how do you add or remove a shard without causing an unmanageable spike in cache misses?

Of course, we could shard our underlying database instead of, or in addition to caching. If the database has a built-in in-memory cache, sharding the data would allow us to keep more of our data in working memory without an additional caching layer! Database sharding has some of the same challenges as cache sharding. Adding and removing shards can be painful, as can migrating the schema without site downtime. That said, some NoSQL databases have great sharding systems built right in, like Cassandra.

This should get our database reads nice and fast.

The next bottleneck might be processing the actual web requests. To remedy this, we should set up multiple web server workers. We can put them all behind a load balancer that distributes incoming requests across the workers. Having multiple web servers adds some complexity to our database (and caching layers) that we'll need to consider. They'll need to handle more simultaneous connections, for example. Most databases are pretty good at this by default.

Okay, now our redirects should go pretty quick, and should be resilient to load spikes. We have a solid system that fits all of our design goals!

- We can store a lot of links.

- Our shortlinks are as short as possible.

- Following a shortlink is fast.

- The shortlink follower is resilient to load spikes.

Bonus

As with all system design questions, there are a bunch more directions to go into with this one. A few ideas:

- At some point we'd probably want to consider splitting our link creation endpoint across multiple workers as well. This adds some complexity: how do they stay in sync about what the

current_random_slug_idis? - Uptime and "single point of failure" (SPOF) are common concerns in system design. Are there any SPOFs in our current architecture? How can we ensure that an individual machine failure won't bring down our whole system?

- Analytics. What if we wanted to show users some analytics about the links they've created? What analytics could we show, and how would we store and display them?

- Editing and deleting. How would we add edit and delete features?

- Optimizing for implementation time. We built something optimized for scale. How would our system design be different if we were just trying to get an MVP off the ground as quickly as possible?

MillionGazillion

I'm making a search engine called MillionGazillion™.

I wrote a crawler that visits web pages, stores a few keywords in a database, and follows links to other web pages. I noticed that my crawler was wasting a lot of time visiting the same pages over and over, so I made a set, visited, where I'm storing URLs I've already visited. Now the crawler only visits a URL if it hasn't already been visited.

Thing is, the crawler is running on my old desktop computer in my parents' basement (where I totally don't live anymore), and it keeps running out of memory because visited is getting so huge.

How can I trim down the amount of space taken up by visited?

Hint 1

Notice that a boatload of URLs start with "www."

Hint 2

We could make visited a nested dictionary where the outer key is the subdomain and the inner key is the rest of the URL, so for example visited['www.']['google.com'] = True and visited['www.']['interviewcake.com'] = True. Now instead of storing the "www." for each of these URLs, we've just stored it once in memory. If we have 1,000 URLs and half of them start with "www." then we've replaced characters with just 4 characters in memory.

But we can do even better.

Hint 3

What if we used this same approach of separating out shared prefixes recursively? How long should we make the prefixes?

Hint 4

What if we made the prefixes just one character?

Hint 5 (solution)

Solution

We can use a trie. If you've never heard of a trie, think of it this way:

Let's make visited a nested object where each map has keys of just one character. So we would store 'google.com' as visited['g']['o']['o']['g']['l']['e']['.']['c']['o']['m']['*'] = true.

The '*' at the end means 'this is the end of an entry'. Otherwise we wouldn't know what parts of visited are real URLs and which parts are just prefixes. In the example above, 'google.co' is a prefix that we might think is a visited URL if we didn't have some way to mark 'this is the end of an entry.'

Now when we go to add 'google.com/maps' to visited, we only have to add the characters '/maps', because the 'google.com' prefix is already there. Same with 'google.com/about/jobs'.

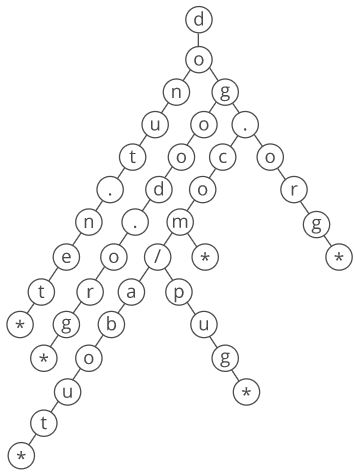

We can visualize this as a tree, where each character in a string corresponds to a node.

A trie is a type of tree.

To check if a string is in the trie, we just descend from the root of the tree to a leaf, checking for a node in the tree corresponding to each character in the string.

Above is a trie containing "donut.net", "dogood.org", "dog.com", "dog.com/about", "dog.com/pug", and "dog.org".

How could we implement this structure? There are lots of ways! We could use nested objects, nodes and pointers, or some combination of the two. Evaluating the pros and cons of different options and choosing one is a great thing to do in a programming interview.

In our implementation, we chose to use nested objects. To determine if a given site has been visited, we just call add_word(), which adds a word to the trie if it's not already there.

class Trie(object):

def __init__(self):

self.root_node = {}

def add_word(self, word):

current_node = self.root_node

is_new_word = False

# Work downwards through the trie, adding nodes

# as needed, and keeping track of whether we add

# any nodes.

for char in word:

if char not in current_node:

is_new_word = True

current_node[char] = {}

current_node = current_node[char]

# Explicitly mark the end of a word.

# Otherwise, we might say a word is

# present if it is a prefix of a different,

# longer word that was added earlier.

if "End Of Word" not in current_node:

is_new_word = True

current_node["End Of Word"] = {}

return is_new_word

If you used a ternary search tree, that's a great answer too. A bloom filter also works-—specially if you use run-length encoding.

Complexity

How much space does this save? This is about to get MATHEMATICAL.

How many characters were we storing in our flat object approach? Suppose visited includes all possible URLs of length 5 or fewer characters. Let's ignore non-alphabetical characters to simplify, sticking to the standard 26 English letters in lowercase. There are different possible 5-character URLs (26 options for the first character, times 26 options for the 2nd character, etc), and of course different possible 4-character URLs, etc. If we store each 5-character URL as a normal string in memory, we are storing 5 characters per string, for a total of characters for all possible 5-character strings (and total characters for all 4-character strings, etc). So for all 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 character URLs, our total number of characters stored is:

So for all possible URLs of length or fewer, our total storage space is:

This is .

How many characters are stored in our trie? The first layer has 26 nodes (and thus 26 characters), one for each possible starting character. On the second layer, each of those 26 nodes has 26 children, for a total of nodes. The fifth layer has nodes. To store all 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 character URLs our trie will have 5 layers. So the total number of nodes is:

So for all URLs of length or fewer, we have:

This is . We've shaved off a factor of .

Bonus trivia: although the HTTP spec allows for unlimited URL length, in practice many web browsers won't support URLs over 2,000 characters.

What We Learned

We ended up using a trie. Even if you've never heard of a trie before, you can reason your way to deriving one for this question. That's what we did: we started with a strategy for compressing a common prefix ("www") and then we asked ourselves, "How can we take this idea even further?" That gave us the idea to treat each character as a common prefix.

That strategy-—starting with a small optimization and asking, "How can we take this same idea even further?"—-is hugely powerful. It's one of the keys to unlocking complex algorithms and data structures for problems you've never seen before.

Find Duplicate Files

You left your computer unlocked and your friend decided to troll you by copying a lot of your files to random spots all over your file system.

Even worse, she saved the duplicate files with random, embarrassing names ("this_is_like_a_digital_wedgie.txt" was clever, I'll give her that).

Write a function that returns an array of all the duplicate files. We'll check them by hand before actually deleting them, since programmatically deleting files is really scary. To help us confirm that two files are actually duplicates, return an array of arrays where:

- the first item is the duplicate file

- the second item is the original file

For example:

[

['/tmp/parker_is_dumb.mpg', '/home/parker/secret_puppy_dance.mpg'],

['/home/trololol.mov', '/etc/apache2/httpd.conf']

]

You can assume each file was only duplicated once.

Since we'll be traversing our file system, we can't solve this with plain JavaScript. We use Node for our solution. You can also change to a server-side language for this challenge.

Hint 1

No idea where to start? Try writing something that just walks through a file system and prints all the file names. If you're not sure how to do that, look it up! Or just make it up. Remember, even if you can’t implement working code, your interviewer will still want to see you think through the problem.

One brute force solution is to loop over all files in the file system, and for each file look at every other file to see if it's a duplicate. This means file comparisons, where is the number of files. That seems like a lot.

Let's try to save some time. Can we do this in one walk through our file system?

Hint 2

Instead of holding onto one file and looking for files that are the same, we can just keep track of all the files we've seen so far. What data structure could help us with that?

Hint 3

We'll use a dictionary. When we see a new file, we first check to see if it's in our dictionary. If it's not, we add it. If it is, we have a duplicate!

Once we have two duplicate files, how do we know which one is the original? It's hard to be sure, but try to come up with a reasonable heuristic that will probably work most of the time.

Hint 4

Most file systems store the time a file was last edited as metadata on each file. The more recently edited file will probably be the duplicate!

One exception here: lots of processes like to regularly save their state to a file on disk, so that if your computer suddenly crashes the processes can pick up more or less where they left off (this is how Word is able to say "looks like you had unsaved changes last time, want to restore them?"). If your friend duplicated some of those files, the most-recently-edited one may not be the duplicate. But at the risk of breaking our system (we'll make a backup first, obviously.) we'll run with this "most-recently-edited copy of a file is probably the copy our friend made" heuristic.

So our function will walk through the file system, store files in an object, and identify the more recently edited file as the copied one when it finds a duplicate. Can you implement this in code?

Hint 5

Here's a start. We'll initialize:

- a dictionary to hold the files we've already seen

- a stack (we'll implement ours with an array) to hold directories and files as we go through them

- an array to hold our output arrays

def find_duplicate_files(starting_directory):

files_seen_already = {}

stack = [starting_directory]

# We'll track tuples of (duplicate_file, original_file)

duplicates = []

while len(stack) > 0:

current_path = stack.pop()

return duplicates

(We're going to make our function iterative instead of recursive to avoid stack overflow.)

Hint 6

Here's one solution:

import os

def find_duplicate_files(starting_directory):

files_seen_already = {}

stack = [starting_directory]

# We'll track tuples of (duplicate_file, original_file)

duplicates = []

while len(stack) > 0:

current_path = stack.pop()

# If it's a directory,

# put the contents in our stack

if os.path.isdir(current_path):

for path in os.listdir(current_path):

full_path = os.path.join(current_path, path)

stack.append(full_path)

# If it's a file

else:

# Get its contents

with open(current_path) as file:

file_contents = file.read()

# Get its last edited time

current_last_edited_time = os.path.getmtime(current_path)

# If we've seen it before

if file_contents in files_seen_already:

existing_last_edited_time, existing_path = files_seen_already[file_contents]

if current_last_edited_time > existing_last_edited_time:

# Current file is the dupe!

duplicates.append((current_path, existing_path))

else:

# Old file is the dupe!

# So delete it

duplicates.append((existing_path, current_path))

# But also update files_seen_already to have

# the new file's info

files_seen_already[file_contents] = (current_last_edited_time, current_path)

# If it's a new file, throw it in files_seen_already

# and record the path and the last edited time,

# so we can delete it later if it's a dupe

else:

files_seen_already[file_contents] = (current_last_edited_time, current_path)

return duplicates

Okay, this'll work! What are our time and space costs?

Hint 7

We're putting the full contents of every file in our object! This costs time and space, where is the total amount of space taken up by all the files on the file system.

That space cost is pretty unwieldy—-we need to store a duplicate copy of our entire filesystem (like, several gigabytes of cat videos alone) in working memory!

Can we trim that space cost down? What if we're okay with losing a bit of accuracy (as in, we do a more "fuzzy" match to see if two files are the same)?

Hint 8

What if instead of making our object keys the entire file contents, we hashed those contents first? So we'd store a constant-size "fingerprint" of the file in our object, instead of the whole file itself. This would give us space per file ( space overall, where is the number of files)!

That's a huge improvement. But we can take this a step further! While we're making the file matching "fuzzy," can we use a similar idea to save some time? Notice that our time cost is still order of the total size of our files on disk, while our space cost is order of the number of files.

Hint 9

For each file, we have to look at every bit that the file occupies in order to hash it and take a "fingerprint." That's why our time cost is high. Can we fingerprint a file in constant time instead?

Hint 10

What if instead of hashing the whole contents of each file, we hashed three fixed-size "samples" from each file made of the first bytes, the middle bytes, and the last bytes? This would let us fingerprint a file in constant time!

How big should we make our samples?

Hint 11

When your disk does a read, it grabs contents in constant-size chunks, called "blocks."

How big are the blocks? It depends on the file system. My super-hip Macintosh uses a file system called HFS+, which has a default block size of 4Kb (4,000 bytes) per block.

So we could use just 100 bytes each from the beginning middle and end of our files, but each time we grabbed those bytes, our disk would actually be grabbing 4000 bytes, not just 100 bytes. We'd just be throwing the rest away. We might as well use all of them, since having a bigger picture of the file helps us ensure that the fingerprints are unique. So our samples should be the the size of our file system's block size.

Hint 12 (solution)

Solution

We walk through our whole file system iteratively. As we go, we take a "fingerprint" of each file in constant time by hashing the first few, middle few, and last few bytes. We store each file's fingerprint in an object as we go.

If a given file's fingerprint is already in our object, we assume we have a duplicate. In that case, we assume the file edited most recently is the one created by our friend.

import os

import hashlib

def find_duplicate_files(starting_directory):

files_seen_already = {}

stack = [starting_directory]

# We'll track tuples of (duplicate_file, original_file)

duplicates = []

while len(stack) > 0:

current_path = stack.pop()

# If it's a directory,

# put the contents in our stack

if os.path.isdir(current_path):

for path in os.listdir(current_path):

full_path = os.path.join(current_path, path)

stack.append(full_path)

# If it's a file

else:

# Get its hash

file_hash = sample_hash_file(current_path)

# Get its last edited time

current_last_edited_time = os.path.getmtime(current_path)

# If we've seen it before

if file_hash in files_seen_already:

existing_last_edited_time, existing_path = files_seen_already[file_hash]

if current_last_edited_time > existing_last_edited_time:

# Current file is the dupe!

duplicates.append((current_path, existing_path))

else:

# Old file is the dupe!

duplicates.append((existing_path, current_path))

# But also update files_seen_already to have

# the new file's info

files_seen_already[file_hash] = (current_last_edited_time, current_path)

# If it's a new file, throw it in files_seen_already

# and record its path and last edited time,

# so we can tell later if it's a dupe

else:

files_seen_already[file_hash] = (current_last_edited_time, current_path)

return duplicates

def sample_hash_file(path):

num_bytes_to_read_per_sample = 4000

total_bytes = os.path.getsize(path)

hasher = hashlib.sha512()

with open(path, 'rb') as file:

# If the file is too short to take 3 samples, hash the entire file

if total_bytes < num_bytes_to_read_per_sample * 3:

hasher.update(file.read())

else:

num_bytes_between_samples = (

(total_bytes - num_bytes_to_read_per_sample * 3) / 2

)

# Read first, middle, and last bytes

for offset_multiplier in range(3):

start_of_sample = (

offset_multiplier

* (num_bytes_to_read_per_sample + num_bytes_between_samples)

)

file.seek(start_of_sample)

sample = file.read(num_bytes_to_read_per_sample)

hasher.update(sample)

return hasher.hexdigest()

We've made a few assumptions here:

Two different files won't have the same fingerprints. It's not impossible that two files with different contents will have the same beginning, middle, and end bytes so they'll have the same fingerprints. Or they may even have different sample bytes but still hash to the same value (this is called a "hash collision"). To mitigate this, we could do a last-minute check whenever we find two "matching" files where we actually scan the full file contents to see if they're the same.

The most recently edited file is the duplicate. This seems reasonable, but it might be wrong—-for example, there might be files which have been edited by daemons (programs that run in the background) after our friend finished duplicating them.

Two files with the same contents are the same file. This seems trivially true, but it could cause some problems. For example, we might have empty files in multiple places in our file system that aren't duplicates of each-other.

Given these potential issues, we definitely want a human to confirm before we delete any files. Still, it's much better than combing through our whole file system by hand!

Some ideas for further improvements:

- If a file wasn't last edited around the time your friend got a hold of your computer, you know it probably wasn't created by your friend. Similarly, if a file wasn't accessed (sometimes your filesystem stores the last accessed time for a file as well) around that time, you know it wasn't copied by your friend. You can use these facts to skip some files.

- Make the file size the fingerprint—-it should be available cheaply as metadata on the file (so you don't need to walk through the whole file to see how long it is). You'll get lots of false positives, but that's fine if you treat this as a "preprocessing" step. Maybe you then take hash-based fingerprints only on the files which which have matching sizes. Then you fully compare file contents if they have the same hash.

- Some file systems also keep track of when a file was created. If your filesystem supports this, you could use this as a potentially-stronger heuristic for telling which of two copies of a file is the dupe.

- When you do compare full file contents to ensure two files are the same, no need to read the entire files into memory. Open both files and read them one block at a time. You can short-circuit as soon as you find two blocks that don't match, and you only ever need to store a couple blocks in memory.

Complexity

Each "fingerprint" takes time and space, so our total time and space costs are where is the number of files on the file system.

If we add the last-minute check to see if two files with the same fingerprints are actually the same files (which we probably should), then in the worst case all the files are the same and we have to read their full contents to confirm this, giving us a runtime that's order of the total size of our files on disk.

Bonus

If we wanted to get this code ready for a production system, we might want to make it a bit more modular. Try separating the file traversal code from the duplicate detection code. Try implementing the file traversal with a generator!

What about concurrency? Can we go faster by splitting this procedure into multiple threads? Also, what if a background process edits a file while our script is running? Will this cause problems?

What about link files (files that point to other files or folders)? One gotcha here is that a link file can point back up the file tree. How do we keep our file traversal from going in circles?

What We Learned

The main insight was to save time and space by "fingerprinting" each file.

This question is a good example of a "messy" interview problem. Instead of one optimal solution, there's a big knot of optimizations and trade-offs. For example, our hashing-based approach wins us a faster runtime, but it can give us false positives.

For messy problems like this, focus on clearly explaining to your interviewer what the trade-offs are for each decision you make. The actual choices you make probably don't matter that much, as long as you show a strong ability to understand and compare your options.